Despite regional differences and identity quests, the strength of Indian nationhood persists, supported by a dedication to constitutional values and productive conversations

There is much talk about the nature of change in all aspects of Indian life, as is natural in changes envisaged at such a large scale. There are bound to be differences of opinion, multiple articulations, and an attempt to project one’s point of view. This is how it should be. This is amplified by the Sanskrit dictum “Vade Vade Jayat Tatva Bodhah” (through discussion one arrives at the truth). However, discussion must follow a protocol. This protocol is often unwritten and is a bedrock of any civil society. It has some enduring principles. The first and foremost of which would be that it cannot be and must not be abusive.

The right to civil disagreement in a civil manner is the foundation of a civil society. Thus, it is that mutual respect and agreeing to disagree are required as essential to civil discourse.

One can add to it, for good measure, certain other attributes and certain attributes of the mind. These attributes recognise the need to not only listen but honestly weigh the merits of another person’s point of view and have a genuine openness to consider it.

Agreeing to another point of view or modifying one’s own in a civil society is not a hallmark of weakness but a source of genuine strength and maturity. Going by these principles, the Indian civil society has an interesting record with significant regional variations. The Dravid school of thought is an interesting example. They are saying in the twenties of this century, roughly the same things they were saying in the thirties of the last century.

The Dravidian leadership has in the last seventy-five years then been in power in that part of India for several decades, though not always continuously.

Similarly, the exclusionist identity sought by some of the DMK ideologues has had on various occasions to be moderated because they have been in power. Notwithstanding long patches of time, not much significant progress has been made in the implementation of some of the components of the DMK ideology, such as it may be. The ideological component itself has undergone a major split with an exclusivist ideology for DMK being considerably whittled down in the birth of All India Anna Dravid Munnetra Kazhagam (AIDMK). M.G. Ramachandran was the major proponent of the AIDMK version. Jayalalithaa was a key supporter. They linked up with the Dravidian Movement with all Indian processes. How it panned out is another story and fit enough for another discussion.

More to the point, it is important to realise that similar identity quests or some version thereof have been witnessed in the North Eastern States, Jammu & Kashmir State, parts of Andhra Pradesh, and a few other pockets of the southern Indian peninsula. This is a very understandable process. By and large, it has been contained within the constitutional framework. At times the divergent point of view has been espoused by neighbouring states of the Deccan peninsula or between the Deccan States and the Central Government at New Delhi over many matters including the distribution of river waters.

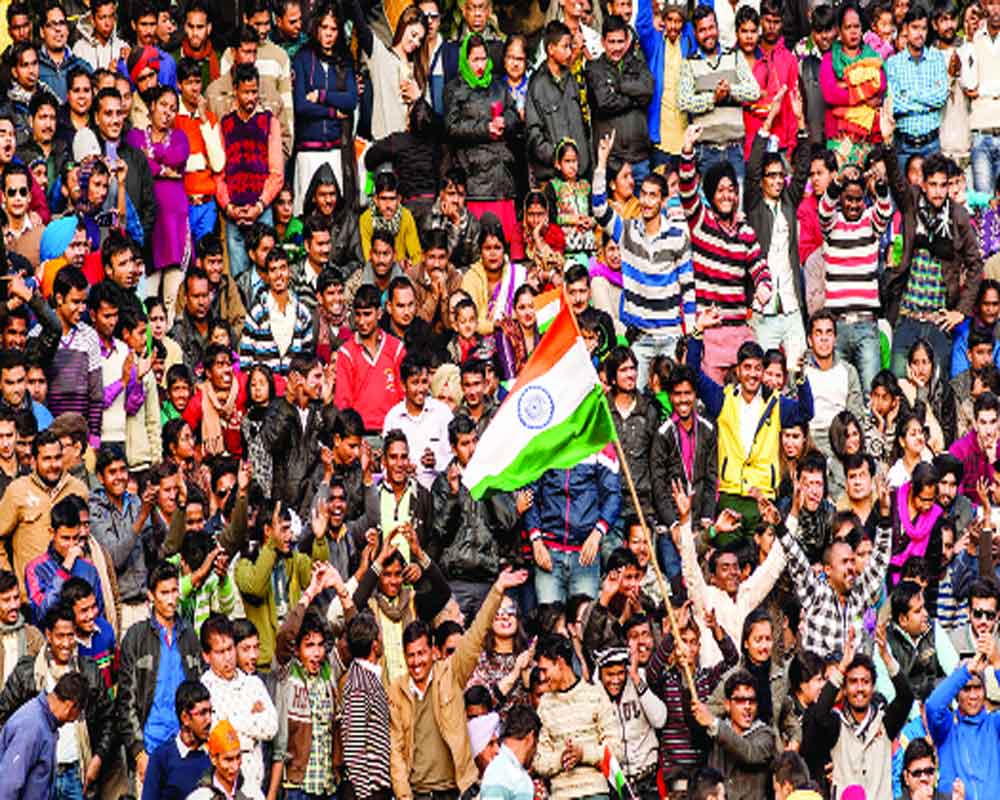

Notwithstanding these differences, Indian nationhood has endured and might even be seen as having gone from strength to strength. It is this resilience which is, also, the hallmark of Indian nationhood. This is not to deny the fact that once in a while, offensive or extreme statements are made, some of which are avoidable, though sometimes understandable.

The long and short of it is the ability of people to work together despite differences and different articulations.

More to the credit of everyone concerned is the urge on the part of most people to evoke the Indian Constitution whenever need be and not practice brinkmanship. The time is here to ensure that these practices of healthy debate and the setting of shared perspectives become a regular habit and a part of the national methodology of dialogue and discussion.

Sometimes when extreme statements are made and some new thinking seems to arise, there is nothing wrong with that either, only that the model of integrative thinking would have to show far more resilience than it is many times currently showing.

This text has looked at the vantage point of collective cohesion. It is not as if there are no dangerous signs that need to be tackled, but that attempting to tackle them sensibly and systematically is necessary. It is this institutionalisation of handling dissent and allowing seemingly alternative perspectives to live peacefully with each other that will be the touchstone on which much of the future of Indian nationhood will continue to flourish.

In an era where subtle dissent becomes a part of covert political strategy, much care needs to be exercised. The number game can have dangerous manifestations. There is no substitute for good sense and integrity of thought, deed, and follow-up.

(The writer is a well-known management consultant of international repute. The views expressed are personal)