Those of us who have grown up reading and believing that the integration of Sikkim into the Indian Union had been driven by an overwhelming desire of its people to join this country, Sunanda K Datta-Ray’s book will provide a rude jolt, writes RAJESH SINGH

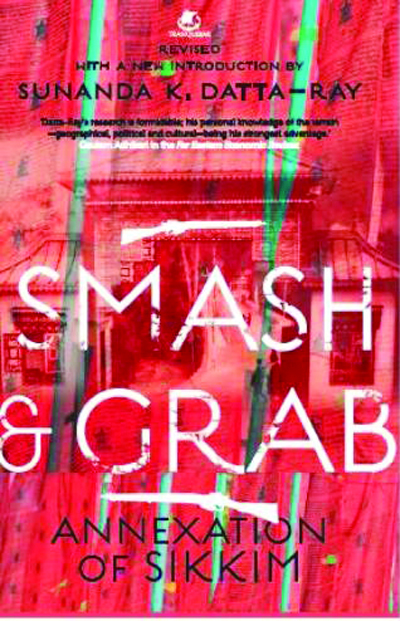

Smash and Grab: Annexation of Sikkim

Author: Sunanda K Datta-Ray

Publisher: Tranquebar, Rs 795

Those of us who have grown up reading and believing that the integration of Sikkim into the Indian Union had been driven by an overwhelming desire of its people to join this country, will be rudely jolted by Sunanda K Datta-Ray’s narrative in Smash and Grab: Annexation of Sikkim. In what is perhaps the most authentic account of the historic event, the author proceeds to smash the long-held perception of a benign New Delhi stepping in to offer ‘relief’ to the ‘suffering’ people of Sikkim, and grab the reality which the authorities have carefully hidden behind the curtains since the “annexation” — this is what Datta-Ray unapologetically terms the manner in which Sikkim was taken into the Indian fold — happened in April 1975.

His sensational narrative had come into the open barely 10 years after the monumental event, but the book had mysteriously disappeared from the market. It is widely believed that the Indian establishment had moved swiftly to ensure that nobody — or only the least number of people — got to read the truth. The recent arrival of the book, now in a revised version, was therefore more of a re-release, in the hope that this time around Smash and Grab will remain accessible to the public at large. In any case, a repeat of the 1984 clampdown could not be possible now. With the advent of information technology and 24x7 television even banned books are discussed, and accessed surreptitiously. Indeed, they end up attracting more readership than they may have without the accompanying free publicity. One marketing tool for Datta-Ray’s book can be the following: “Here is a book that had been sent underground by the Government in 1984 because it spoke the truth. Now, the book is back in the market. Read the true story of the annexation of Sikkim by India”!

This may sound sensational for a book on history, but read it and you will agree that it deserves to be bracketed among the raciest accounts written on a historical (and historic) event. It is not that Datta-Ray pre-determined that he would do so, but the material at his disposal must have led him to a narrative that could not have been otherwise. Unlike many authors who write on historical events from a distance, not having had the privilege of living through them, Datta-Ray was in the thick of things in Sikkim. He had been reporting from the former kingdom forThe Statesman and The Observer of london as a journalist, had developed a network of contacts within the palace and among officials of the Government of India who had played roles in shaping the destiny of Sikkim — for better or worse — and was perhaps the only journalist then to have first-hand account of the drama that preceded the “annexation” and immediately thereafter.

The core of Smash and Grab — the brutish title derives from the exact words that the Chogyal had uttered more in shock than in anger when he learnt that Indian troops had launched an attack against his tiny kingdom — is that the ‘annexation’ of Sikkim by India was neither necessary nor justified. To add here, neither were the aggressive means, reserved for enemy nations, appropriate. As Datta-Ray points out, Sikkim had maintained excellent relations with New Delhi since India’s Independence and was happy being a ‘Protectorate’ of India. It had done nothing to invite a takeover by force. The monarch had warm relations with Indian leaders, beginning from Jawaharlal Nehru down to Indira Gandhi. Yet, the atmosphere was vitiated partly due to the games that the bureaucracy in India played, partly because of a phobia which existed in the minds of the Indian leadership over the palace’s affinity towards certain sections that New Delhi believed were inimical to its interests, and partly due to the shenanigans of prominent political leaders of Sikkim who worked internally to weaken the Chogyal’s authority, sow seeds of distrust and fuel unrest among the people.

Although it was during Indira Gandhi’s tenure that Sikkim got added — or ‘annexed’ — to the Indian Union, the grounds were laid during Jawaharlal Nehru’s time as the Prime Minister. This is ironic, because Nehru had said in mid-June: “If we bring a small country within our fold by using force, it would be like killing a fly with a bullet.” The author, therefore, rightly devotes a large space to the relationship between India and Sikkim throughout Nehru’s term. He explains how things had already begun to fall apart and how the seeds of mutual suspicion had begun to be laid. If they began to sprout soon after, somehow the differences did not reach a flashpoint. The political officers who represented the Government of India in Sikkim during the Chogyal rule were often busy playing divide-and-rule games, aided and abetted by their bosses in New Delhi. Worse, many of them were imperious in nature and believed that the palace in Sikkim should remain subservient to the region’s big brother. They lost no opportunity, as Datta-Ray relates in instances, in seeking to humiliate the king, widely respected and revered as well on matters of spiritual lineage. It cannot be that Nehru did not know of the happenings, but he remained ambivalent at best and irritating at worst. Indira Gandhi, though, believed that Sikkim had lived long enough as an independent nation.

Interestingly, as the author points out, both Nehru and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel had never seriously believed any meaningful purpose could be served in having Sikkim as a part of the Indian Union. He writes, “Much was written later about Nehru’s feeling for the mountains. But romantic attachment to a terrain he had not even visited when his policy was formulated could not run away with his political judgement. Patel and (VP) Menon, both single-minded men unmoved by sentiment, certainly could not have succumbed to any such emotion. More plausible is the inference that while they would have liked to merge Sikkim, they appreciated that even the successor government in New Delhi could not aspire to inherit powers that its viceregal predecessors had not enjoyed. Therefore, they sought Gangtok’s consent to continued diplomatic relations.”

Here, Datta-Ray points that Gangtok could have refused the request. But it did not, and the two entered into a standstill agreement — after it became clear that India accepted Sikkim as an independent entity. This act of friendship on Sikkim’s part does not seem to have influenced New Delhi’s conduct towards the Himalayan kingdom in later years. No purpose will be served in attempting to relate the furious pace of events that led to the ‘annexation’, and the role that several characters — some colourful, others devious, and several more opportunistic — played in the act. This is best understood by reading the book. But Smash and Grab is not just history; it is a tale of human greed for power and leverage, and the downfall of a proud and benign, if somewhat ineffective and largely trusting, monarch.