The Kochi biennale has pushed key frontiers in global dialogue, snapping the exclusionary stiffness of art fairs, where the plight of the dispossessed is merely a motif and not felt anguish

Young Ahalya from Kollam, who grew up in a pineapple farm, loved the fruit’s colours so much that she decided to express herself through them and turned painter. As she filled up her canvas with intricate scenes of plantation life, replicating her hard-working parents’ faces on the figures that peopled it, she surrounded them with hills and forests, nature in a flaming surge as it were, pushing the pylons of civilisation in a distant greyness. Her fellow artists have picked up a morbid rubble tossed up by the Kerala floods and strung them to a twisted spinal cord, which is straightening itself in a desperate lunge at survival. There’s Pangrok Sulap from Malaysian Borneo, another artist born of the soil, dancing on a canvas spread taut on wood-cut blocks depicting farm life and issues, his happy feet imprinting his memories of them. All of them have stitched together their peasant origins and come together at the Kochi Muziris Biennale, which is unshackling art from the confines of rarefied thought and elitism to listen to the sub-terranean voices and helping them stake a claim in contemporary discourse.

If art biennales are meant to rearticulate the times, then the Kochi edition has clearly pushed key frontiers in global dialogue, snapping the exclusionary stiffness of art fairs and museums, where the plight of the dispossessed is merely the motif and not the felt anguish of those who go through it. As its curator, artist Anita Dube has attempted to explore “possibilities of a non-alienated world” and managed to address the elephant in the room, to create a safe public sphere where we can think freely, exchange ideas, ask questions of ourselves, have conversations and dialogue rather than ideological loud-mouthing and best of all provide a safe pedagogic haven where people do not feel threatened, judged or not qualified enough. In this respect, the Kochi biennale has fully given credence to sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s argument for the need to create a social and cultural capital juxtaposed to the economic one. He had defined “cultural capital” as that which determined the “tastes” of society, which, if not wholesome and representative enough, can perpetuate a cycle of privilege instead of breaking it down. Museums and galleries may lend us access to all sorts of artwork that have emerged as an interpretation of history, context and archives but what of sensitive story-telling? Will it be a projection of an idea rather than a humane experience? The Kochi biennale hasn’t talked down, it has allowed everyone to come in. Or as Dube described it, enfolded them in the “discursive frame of culture.” Be it an attempt at post-colonial redemption by the West, the resolution of anxieties, the fluidity of identities, the retrieval of protest poetry from conflict zones, the reinstatement of women’s dues, like that of the selfless Malayali nurses, the cry for ecological justice, the siege of micro-cultures or the much-revered cow head turning into a fist of agrarian assertion, every voice has been respected and interpreted in concrete, tactile and visually explosive terms. For public engagement of art cannot happen unless it appeals to our sensorium. And till that is done, till art also becomes a source of pleasure, populism will continue to cede space to majoritarian monologues. Should that be easily handed over? Shouldn’t populism be a happy prospect than be demonised as a takeover tool of everybody’s trade?

In that sense, the Kochi biennale has already started the process of culture reclamation as a democratic nurturing of ideas, not a handed down rewriting of scripts. Muziris was an ancient port on the Malabar coast, our first point of globalisation over centuries as merchant ships plied the spice routes and broke down barriers for a confluence and assimilation of cultures. Perhaps this biennale rescued that ancient spirit and applied it to the current context.

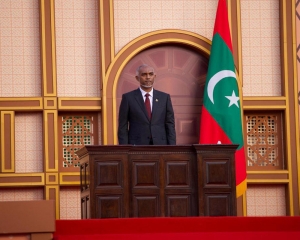

For Kerala, a State that was ravaged brutally by the floods barely a hundred days ago —1.5 million people displaced and 200,000 lives lost — the biennale has been a huge palliative. Many had questioned if the Government should go through with this edition and not divert the usual funds to the reconstruction process. But Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan wanted to send out the message that Kerala is resilient and means business. The spinoff effects on the economy by way of tourism, services and infrastructure are for all to see. The laid-back Fort Kochi area is now a bustle, the waterways have emerged as transport corridors ferrying people from one island to another, the local youth have signed up as volunteers and most residents have opened up homestays and cafes. Warehouse owners, who do booming business in a port town, have let out spaces for three months to make way for installation artists. And abandoned houses are getting a new lease of life. More so, the people of Kochi, who have virtually owned this art event as their badge of pride through the past years, don’t want to let go of it. Students and young people are toggling assignments and work to play hosts and coordinators. Thousands of carpenters are at work, helping erect structures and artworks, the caterers have never been busier, feeding visitors on the roadside and the auto wallahs have replaced the need for Google maps.

The Chief Minister himself inaugurated the biennale, lending a heft to proceedings and insisting in his speech that the traumatised State indeed needed to heal itself through art. The biennale has done up drab walls in hospitals and dressed up worn out facades with colourful murals to mask the darkness of pain. Over the years, organisers have reached out to schools and made entry free on certain days for the common people to access and embrace a different form of expression. This is the process by which an auto rickshaw driver like Bapi Das was inspired enough to embroider his thoughts on fabric, now on prominent display. Or a runaway like Vicky Roy, who grew up in a shelter home near the New Delhi Railway station and who was trained in a photography workshop, to reframe the urbanscape through his lens and awaken us to the trickle-down effects of societal statutes and policy-making. Like Ahalya, they were not empowered by birth, be it in terms of access to language or chance. They evolved on their own, organically and untutored. Kerala clearly isn’t shedding a tear for itself.

Of course, what’s art without the political subtext? And there were plenty at the biennale posited against the visual epidemic of clichés on other media. At a time when the women artistes’ collective have articulated their brand of #MeToo in the Malayali film industry and faith debates on Sabarimala continue to hover over a woman’s right to enter the shrine, the biennale has had its first woman curator and devoted more than 50 per cent of the works to women artists. The Guerrilla Girls, who have been talking about sexism in the arts field through provocative slogans and street performances, have plastered the town with placards, asking questions about whether women are only good as models for artists and if gallery staff get respectable pay. Kashmiri artist Veer Munshi has recreated a Sufi shrine with lacquer coffins of the young, arguing for the middle path in dialogues and a return to civilisational contiguity that has been torn asunder by extremism. A young performance artist frisks entrants to peacefully demonstrate his angst of growing up behind the wired quarters. That speaks louder than the gun.

In the end, art anywhere should be about the relational dynamic between the creator and the audience. Only then can it be a vibrant cultural asset and offset hierarchies set by economic and political structures. Or to borrow words from the Guerrilla Girls, “Don’t let museums reduce art to a small number of artists who have won a popularity contest among big-time dealers, curators and collectors. If museums don’t show art as diverse as the cultures they claim to represent, tell them they’re not showing the history of art, they are just preserving the history of wealth and power.” The sea winds have brought a whiff of life to Kochi.

(The writer is Associate Editor, The Pioneer)