Kunwar Narain expresses a cultural confidence that distinguishes him from all those who harboured serious misgivings about the distinctiveness of indigenous traditions and nativist tendencies

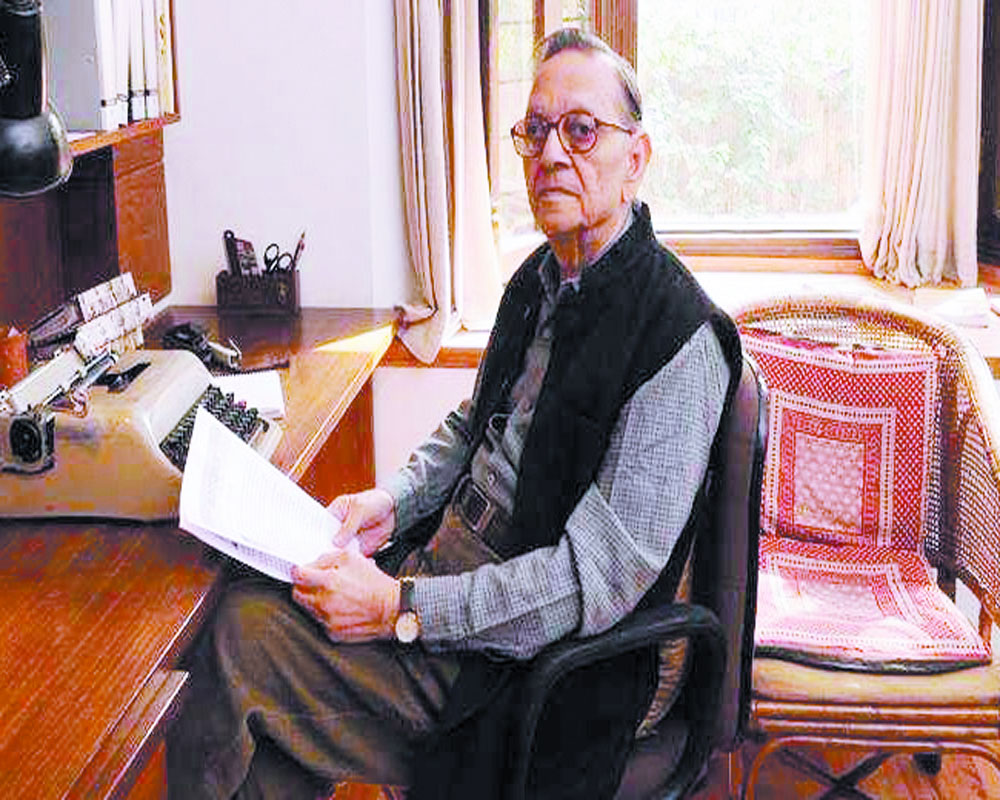

Kunwar Narain was a literary icon, who with his exceptionally refined literary sensibility, stylistic as well as linguistic sophistication, and a tremendous sense of humanism embedded in native traditions, made enduring contributions to Indian literature. He brought back not just enormous accolades for his immensely impressive creative output in various genres such as poetry, short-story, translation, literary criticism, and writings on cinema and music, but also numerous awards and honours that include the Sahitya Akademi Award, the Padma Bhushan, the Sahitya Academi Senior Fellowship and the Jnanpith Award. His literary endeavours chart a trajectory to explore those possibilities that can effectively strengthen core human values in a deeply divided and perpetually painful modern world where prerequisites for a peaceful and satisfying co-existence are increasingly being ignored.

Narain is often said to be a highly contemplative and visionary bard who chose to creatively engage with some of the fundamental questions surrounding human existence. Issues that kept the practitioners of the Upanishad and the followers of Buddhist thought wide awake come to occupy a central space in Narain’s poetic compositions. The primary objective behind his enormously speculative poetic temperament is to reinforce belief in the primacy of human bonding as well as the supremacy of humanitarian perspectives of life. Drawing upon information and insight, knowledge and wisdom gathered from both historical and mythical characters such as Sarhapa, Abhinavgupta, Kumarjiva, Amir Khusro and Gandhi, Narain preferred to weave an interesting and inspiring web. This made it evident that he possessed a credible historical sense. Even when he employed mythical figures for his poetic purposes, he never lost sight of historical sense that enabled him relocate those figures. This helped him render them absolutely meaningful in a contemporary social and cultural set-up. Additionally, it helped him find out plausible solutions to those lingering problems that had been major concerns for the modern society.

His historical sense did not allow anyone draw divisive lines among individuals. Instead, it made an earnest attempt to put hostile people together for the sake of forging a harmonious relationship between them. This kind of inclusive approach with an explicit optimism suggests Narain’s unflagging commitment to the essence of nativist ideas and principles that appear to govern his poetic preoccupations.

In his very first collection of poetry, Chakravyuh, Narain made it very clear that he had a deep desire and high aspiration apart from those ordinary ones that defined the existence of people who were happy and content with the fulfilment of their immediate material needs and requirements. It was precisely an acute awareness about those deep desires and high aspirations that set creative fertile minds apart and explained their pre-occupations.

The way Abhimanyu, his heroic character in Chakravyuh, does not flinch even an inch in the face of impending death and instead displays remarkable courage and extraordinary skill of warfare while fighting against a gang of deceitful warriors on the other side suggests a certain kind of sincerity and dedication that gives a definite purpose to contemporary people to sustain themselves even during the worst phases of their lives.

Narain brought another heroic figure Nachiketa into the picture in two other poetry collections namely Atmajayi and Vajasrava ke Bahane. Nachiketa asks extremely difficult questions to Yama and his own father, Vajasrava, about death and existence, attachment and renunciation respectively. Nachiketa story was taken from Kathopanishad, but it was employed to give it a contemporary meaning. Here. we may also seek an adequate answer to questions about human life, its annihilation and truths about the existence of an afterlife.

Issues raised by Narain in these collections were relevant for contemporary readers precisely because they motivated them to meaningfully engage with the highly unpredictable twists and turns, often mysterious, miraculous and even monstrous pulls and pressures of human life with a view to encourage them to think along the lines of living a purposeful and productive life, and not just a superficially happy and materially sound one.

In his other collections of poems, Narain proved to be an extremely successful poet who was almost always immaculate in his selection of language, impeccable in his treatment of content and extremely careful about the idea of enriching the genre of Hindi poetry itself.

While Narain was most famous for his praiseworthy poetry, he had written wonderful short stories too. His two collections of short stories — Akaron ke Aaspaas and Bechain Patton ka Koras — were particularly praised for their evocative expressions of contemporary realities in such a way that his concerns for the cultivation of a sense of moral discrimination and genuine commitment to humanitarian principles were much obvious.

While reading these stories, readers get curious before getting poignantly conversant with the protagonists, subject matter they deal with and the ambience they create in those stories. For instance, Gudiyon ka Khel not only underlines the struggles and hardships of brother-sister duo who conduct the circus, but also highlights the undercurrents of existential angst and unhappiness of the hero who is otherwise able to manifest a lot of enthusiasm and zeal for the celebration of life. Alongside he shows a great deal of compassion and generosity for the people from the periphery.

Narain posed some tough questions about the kind of moral choices we make in our lives as was evident from the short story Kameej in which an apparently innocent man, who had already renounced the world having sacrificed the material comfort of home with wife and children, is not only put into the bar of judgement but also declared guilty. With the assertion of the plight and indeed despondency of the man named Vireshwar Babu, Narain encouraged us to think through the fallacious nature of judicial structures that ruthlessly sabotage the supposedly good intentions of a seemingly upright man. Despite giving an appropriate voice to deeply disturbing thoughts and emotions associated with the overarching experiences about borderline in Seema Rekha, Narain emphasised on the significance of a compassionate and caring kind of politically neutral humanism.

It is this connecting thread with a profound sense of indigenous humanitarian outlook that prompted Narain to avoid all kinds of polemical criticism of art and literature. Such criticisms tend to ignore the need to understand intricacies and complexities behind the creative processes of a literary work of art, and remain preoccupied with perpetuating predominance of a particular point of view over others, mostly for personal or political aggrandisement.

Narain the critic never tried to reduce a creative piece to the point of a theoretical premise which often governs ideologically-oriented critics. Perhaps the best way to understand Narain as a critic is to read his creative presuppositions intimately as is amply clear from his way of doing criticisms of celebrated poets like Agyeya, Shamsher and Muktibodh and novelists like Nirmal Verma, Yashpal and Hazari Prasad Dwivedi respectively.

Narain was a living legend. He remained throughout his life remarkably reclusive but effectively articulate in his writings and speeches. An excellent human being who was held in high regard by his contemporaries, he was quite unambiguous in his repudiation of any diktats coming from the arena of politics to unnecessarily influence the sacrosanct journey of poetry. But he was simultaneously candid enough to acknowledge the importance of politics for our modern day existence. It was this clarity of thought about the different roles of politics and literature that enabled him to effortlessly embrace the useful insights being offered by the cultural and philosophical traditions of our country.

Right from his first collection of poetry, Chakravyuh published in 1956 to his last one namely, Kumarjiva published in 2017, and also the posthumous publications of second short story collection called Bechain Patton ka Koras, along with his translations of some to finest poems from world literature, Narain remained preoccupied with a relentless search for harmony exhibiting an indefatigable faith in humanity of the humankind.

In his entire preoccupations, he reflected a rare kind of originality, deep engagement with myths and legends and their inextricably intertwined relationship with contemporary history. He expressed superb cultural confidence that distinguished him from all those who harboured serious misgivings about the distinctiveness as well as the effectiveness of indigenous traditions and nativist tendencies.

(The writer is Assistant professor of English at Rajdhani College, Delhi)