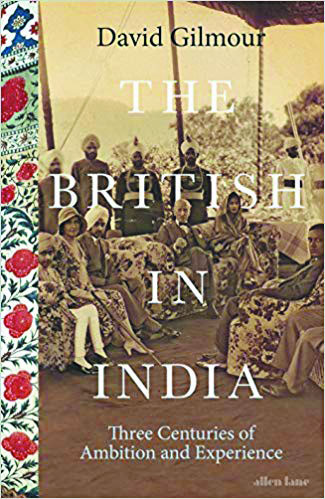

The British in India

Author :David Gilmour

Publisher: Penguin, Rs 999

With a studied focus on the individuals and their unique experiences, this book on India’s colonial past is a rare treat, writes RAMESH AGGARWAL

The book, The British in India: Three Centuries of Ambition and Experience, by David Gilmour looks at the Indo-British relationship from a very different angle. It is written from the point of individuals and is a very interesting read. The British, in this book, lived in India from shortly after the death of Queen Elizabeth I until well into the reign of Queen Elizabeth II, a span of 350 years.

It is like looking at the curriculum vitae of an individual from a personal angle — the relationships formed with people in different organisations, the personal growth, the learning, the cultural influence of different firms, the motivations for joining and leaving and the overall feelings. As David Gilmour mentions himself in the introduction, the book is primarily about individuals. It deals with large groups of people — with soldiers, with insiders (district officers, judges, officers) and numerous others. It talks about different aspects of their experiences: With what aspirations and motivations they came to India, how many of them came, how they came (voyages and journey time and journey experiences as it took 147 days to a minimum of three weeks to come to India), their working lives, the relationships they formed in India, their homes in India, their hobbies in India, and even how some of them felt after returning home to Britain later on. The total focus is on individuals and this is not a book about the politics of the British empire in India, still less a discussion of whether that empire was good or bad.

The book is organised in three parts. Part one, “Aspirations”, talks about the number of British people who came to India, the different motivations that brought them them here, their origin and identities and the voyages and other journeys they took. Part two, “Endeavours”, talks about their working lives, the military life, the working life of judges other senior officials and other people who worked. Part three, “Experiences”, talks about the various components of their overall experience in India: the intimacies and the relationships they formed, their home life, their hobbies and free time occupations, their deaths in India and the experiences of those who returned home later on.

The book begins with a description of how Scottish Comedian Billy Connolly was surprised to learn that he had Indian ancestors, that his great-grandmother, Florence was from Bangalore as her father Daniel Doyle was enlisted in British army as a youth and was sent to India in 1856.

The book then explains how India’s association with riches has a long history and how India dominated British imagination for long. It is shown most brightly in British imagination after 1876 when Disraeli, the then Prime Minister, gratified Queen Victoria’s wish to be made the Empress of India. It then details how British people used to come to India in search of a good fortune: How they embarked on an Indian journey with a feeling of reluctance because it meant separation from family but calculated that rewards would be worth the sacrifice, the way so many people today go to Gulf countries and other countries from India. Many British people came to India for jobs that were simply not available at home without funds or influence. Restlessness at home and a desire to come to India for financial or other reasons was quite common in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Exiling family’s “black sheep” was quite common. Financial disasters were another reason: People putting all their assets into a single investment, a bank that failed, businesses that went under, stocks in a railroad company that crashed, a plantation where crops were destroyed by drought. Henry Cunningham, a successful barrister and journalist in London put all his money in a tea business, went bankrupt and came to India and for the next 21 years worked on problems of Indian law and administration before becoming advocate general in Madras and later judge in High Court in Calcutta. After 1750, British population in India increased and all sorts of opportunities were there. In the second half of nineteenth century, railways offered all kinds of jobs. There were youngsters who wanted to get away from their family in Britain. For most people, the chief allure was India’s wealth and their chance of getting their hands on some of it. For females, India was the place to make a new start after an unhappy relationship in Europe.

Many British families in India were like Dolphin families as they continued generation after generation, usually in the same profession. Four generations of Hancocks served in the Bombay army, Scots in India were spread in a wider range of professions.

The book also explains how for first 200 years of its existence, the East India company paid virtually no attention to training its employees for the work they would be doing in India. In every field, from military to medical, the principle seemed undeviating: Let the chaps learn as they go along. In 1758, the butcher on board a ship of the East India company was allegedly promoted to the job of the ship’s surgeon in the middle of a voyage.

The book also talks about how hard it was to travel: In 1828 John Glasfurd took 147 days to sail to India via the Cape of Good Hope, 20 years later his son took 39 days passing through the Mediterranean and the Red Sea in different boats and 80 years later his grandson only 14 days to reach Mumbai in a single ship. Journey from Calcutta to Delhi that took three days by boat then took three months a generation earlier. Rickshaw (without a bicycle) or a palkee was the most common mode of transport for British people before the railways. In 1844, John Strachey was carried on men’s shoulders for almost a thousand miles from Calcutta to his posting in the North Western Provinces. The journey lasted three weeks but it would have taken much longer by boat.

The main unit of administration was district. In 1902 there were some 250 districts with an average population of a million. The work was slow and bureaucratic. Even during summers when most of the work used to be done from Simla, numerous boxes of files were taken to the hills. Life in the military was boring with repeated marches and drills and in summers the day beginning at 5 am and ending as early as 8 am with nothing to do for the rest of the day.

Until the last decade of the East India company, most British men in India spent at least a part of their adventure living with an Indian or Eurasian woman, often more than one. Referred to as bibi, she was much more than a concubine. Richard Burton, who spent seven years as an officer in India in the 1840s, lauded his first mistress as a nurse, a housekeeper and a teacher of Hindi grammar and Indian culture. Many British people married Indian women and these marriages lasted. Yet, such marriages were a lot less common than the ‘bibi system’.

Bibis also received more concrete proof of affection from the officers. These included servants and allowances and after their lover’s death, legacies. When Major Charles Hay Elliot drew up his will in 1817, he left specific sums to three illegitimate daughters and further Rs 35,000 was set aside for the unborn baby which his bibi was carrying.

Homes used “Khas-tatties” for cooling and a manual fan operated by a servant during the night for cooling before electric fans became common after the end of World War I. Homes had servants for almost everything. In 1807 William Hickey on his departure from Calcutta made a list of the servants to whom he would need to pay three months wages. The number came to 63. It included eight men who waited at table and another eight who looked after his horses.

The last chapter carries a fitting remark by Khushwant Singh, the distinguished writer and journalist. Singh recalls that he had known three types of English persons in India: Those who disliked the country, the dirt, the climate, the smells and indeed the people; those who liked it for what it gave them — the sport, the servants and the standard of living but ignored the Indians and those who had liked everything about India. Such is the understanding of the relationship that the Indians came to share with the British. In each of its aspects, genuine or exploitative, it made history.