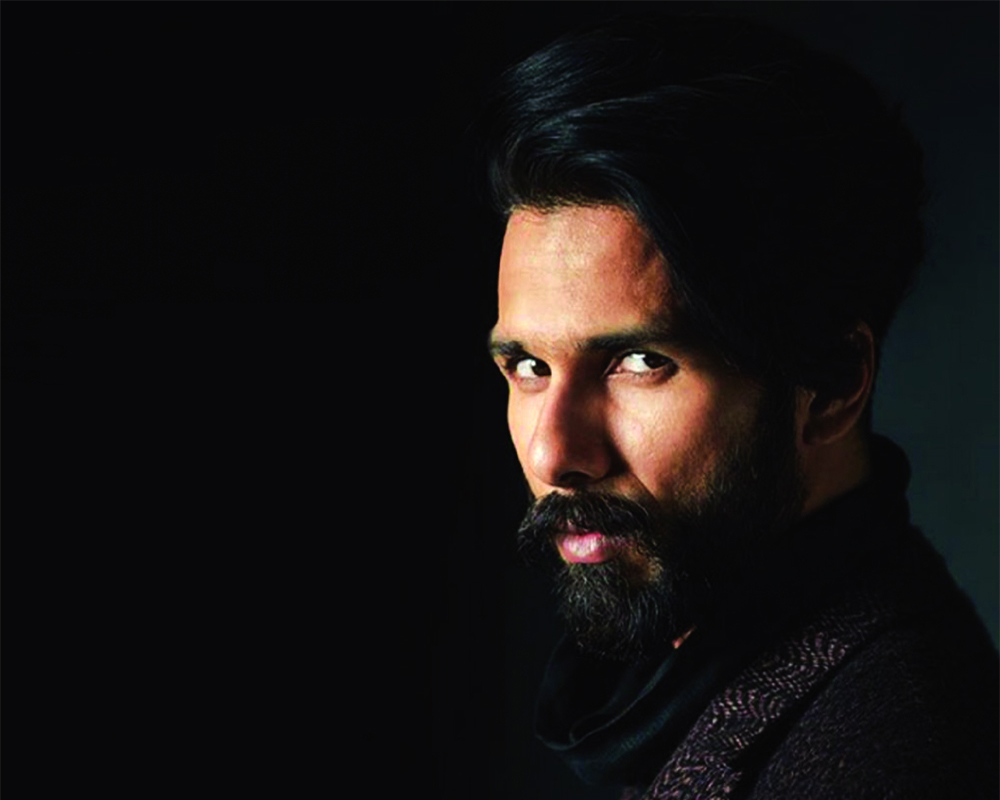

When we meet Shahid Kapoor, he undoubtedly has the laidback elegance of a star in comfortable casuals. But then he asks the photographers to spare him, switches off and settles in for a coffee conversation of sorts, recalling his years of jumping around Press Enclave. That child-like curiosity to explore the world has been the bedrock of the fine actor that he has become. The process wasn’t easy as an industry outsider with chocolate boy looks who danced for fun at a time when content and stories lacked the bandwidth they have today. But he was one of the few who pushed the envelope. Here he is, effervescent, honest, fighter, and forever a student of life with strong family values. Excerpts from an interview with Rinku Ghosh

You credit a lot of your early influences to the way they have shaped you, but obviously, as a person and then the actor you have become. What were those influences?

Growing up in Press Enclave, I was surrounded with journalists, intellectuals and their families, so there was a certain culture vibe. I was quite a naughty kid and very spoilt by my grandparents as I used to live with them. I was very close to my maternal grandfather and my strongest memories are of him dropping me off to school (Gyan Bharati) every morning and the conversations we had. I don’t remember a single day when he didn’t walk me to school. He was an extremely learned man and I was very attached to him, imbibing my fundamentals. So whenever I come to Delhi, it reminds me a lot of my grandfather. In that sense, this city is my influencer.

I think the times that you have spent in life before you became an actor, when you’re living life just as anybody else has, make a very big part of whatever it is that you portray later because those are the associations, memories, and experiences that help you interpret different kinds of situations and scenarios. For example, Batti Gul Meter Chalu is a very grassroot film, a very heartland film. It’s a film about simple people, their problems and their inter-personal relationships and to be able to recreate that as an actor convincingly, you have to draw from certain real life experiences that I have had first-hand.

Is this film a satiric comedy? How would you classify it?

I would say that the film is very quirky and entertaining. I actually feel that there are two films in one film because the first half of the film is about friendships, their inter-currents, dreams and aspirations, and the second half of it is the reality of life as it challenges them, the social issues and electricity being the fundamental human right to access. How power supply sets the everyday tenor of life and how faulty meters and power thefts besiege the common man as he cannot identify the faceless enemy. Where will the aam aadmi (common man) go and raise his voice, who will hear him? Sitting in the comfort of a couch, power pilferage might seem very small and not even make the headlines of the morning newspaper, especially when we read that rural electrification is 100 per cent, but the kind of impact power distribution patterns and their abuse have on ordinary people is huge. There’s actually a three-and-a-half minute speech in the climax of this film, which is a monologue delivered by me and we did it in a single shot. It was a four-page content and it made me cry because it spoke about the problem from a common man’s perspective with facts and logic. India needs to hear this voice. I was very emotionally moved by that speech when I read the script and it stayed with me in much the same manner that certain chapters leave an imprint when you are reading a book. I felt this is the reason why this film should be made. So I signed up.

Haider and Udta Punjab dealt with socially relevant issues. Haider spoke about the issue of human rights in a disturbed area, a very sensitive subject. Tommy Singh revealed the ugly face of youth trapped in the menace of drug abuse. But the issue that really bothers me these days is that of farmers’ suicides. The agrarian crisis is real and pan-India.

How did you process the requirements of these twin roles?

It was very difficult. Shooting Haider, I came across locals, students and others up close and got to know their perspectives. We shot in places that were restricted and where we had just an hour’s permit from the Army. There was a time when our shooting was cancelled and we were told to go back to the hotel and were not explained why. And the next day, we were told there were two known terrorists who had been seen doing a recce of our crew site. Udta Punjab again dealt with a taboo subject. When I heard the script, I was in shock because my understanding of Punjab was very different till then. I was like really, is this happening? And I was told it’s a massive problem. Your perception might be something and that might be even true but this is a growing problem and if you want the rosy perception to stay, then the drug problem has to be addressed, accepted and to be dealt with. Till the time you don’t accept there’s a problem, how will you solve it? Batti Gul... is not as dark as intense. The format is entertaining, accessible and easy to absorb.

There was a time when issue-based films were considered arthouse and then there was the mainstream which dealt with the cliché of the rich-poor divide. Now the lines have blurred and issue-based commercial films have gained commercial credibility. How difficult a job it is to walk the line as an actor?

I find it much easier. Honestly, I used to find it very troublesome when I had to participate in films which were too flighty for my liking. I was 21, so I guess people thought being in college was the only thing I could pull off at that time and that was a huge psychological barrier. My age and my boyish looks were like an impediment in my career because they restricted the offers that came my way. Yeh to dance karta hai, cute lagta hai. I have struggled with that perception for a good 10 years and it is only in the last five years or a bit more that I have been able to reinvent myself. During that time, I have pushed myself very hard to search for and take up offers which weren’t run-of-the-mill or expected of me, which weren’t putting me in a box. I may have lost out on mainstream work in the process but I needed these roles. I think as an actor it is very claustrophobic to inhabit a confined space, though as a star it might be satisfying. There are many cases where people have loved stars for what they have done in a certain space and the latter have done exceedingly well for many years, but that’s not my call.

I have always understood cinema as a way of representing life, telling stories about different people, having different experiences, feeling enriched by those experiences, learning from them and somewhere being impacted by them as a human being. I saw acting as a very enriching opportunity to participate in something that can help you understand life at a really different level. I mean, how many people would be able to do so many different things in one life? So as a profession, acting really excited me because I could get closer to the depth of life’s myriad experiences.

What was the film which changed your image?

It started with Kaminey but I guess the mould started cracking with Jab We Met. I remember there was such a big conversation whether, as a hero, I should wear glasses or not. It used to be so hard to convince everybody back then that glasses would not emasculate the hero. Or that they didn’t signify tragedy or depression. I’m fortunate that Imtiaz (director Imtiaz Ali) was forward thinking and we could do things in that film that might sound so stupid today. Yet, it was a big deal then. I am eternally grateful for my role in Kaminey because it provided me an opportunity to surprise and shock people at the same time and that, as an actor, but happens once in a while. However, it also raised my bar. For me to surprise people that much today is more difficult because they have a certain expectation and reference point. So I have to consistently rediscover myself like I did in Haider or Udta Punjab. The idea is to do different films and be an Indian character from across its geographical sweep. Now, I have Arjun Reddy to explore.

How challenging is Batti Gul after those two intense performances? This one is also a complex character?

He’s the kind of guy you would come across very often in life and most of the time, you wouldn’t like him. I don’t think I’ll be very likeable in the first half of the film because I’m not such a nice guy; I’m pretty self-absorbed and a little full of myself, bit oversmart, cocky, very jugaadu, not necessarily doing the right thing, but obviously very entertaining. The kind of voice used is not very nice to the ears; it’s slightly sharp, roguish, raw with a hard texture. I have tried to make the character what he is. But at some level, he also has to be relatable as a human who fights when he has to.

How do you reconcile the star and the actor within you?

I don’t address the star so much within a film.

But you have become a star over time. So you cannot completely ignore or disregard it either.

I am not disregarding it. I have a huge amount of respect for my fans. I am very grateful for being in that category and I wanted to get there, it’s not like I didn’t. But now I have grown out of the infatuation of being a star. You know an actor is fascinated by this whole concept of being a star and then that kind of becomes his/her guiding force. That’s somehow not the best thing though. I think it’s nice to not take yourself seriously or carry the tag because it’s a baggage that will overload whatever it is that comes your way. I think it’s nicer to know that you happen to be a star but not function on the basis of that. You ought to be an artiste. At least that’s who I am.

Eventually, you have to find yourself. And whatever success you get will be truly relevant when you become original and say something that is different. I have seen people also connect to your truth. Our audience is actually so accepting and sensitive. And the camera never lies, so you’ve got to be honest.

Have you, therefore, eased your position in the fraternity because, let’s face it, there are industry pressures of being seen with the right set of people or circuit. Have you been accepted more than the initial years?

I think fundamentally I see two things that are different. First, I have never been somebody who has been in the centre of the spotlight or wanting to be the most popular person in the room. Having said that, I’d love to know people and them to know me more but that has to happen organically and naturally. I have tried at different times in my career to be someone who I am not and honestly I have not enjoyed it. I think I have my own unique personality, good or bad. And I think 15 years into the fraternity, people may like it or not but have come to terms with it.

Second, I think I am comfortable in my skin and that’s the most important facet for every human being. You are happy with yourself only when you’re happy with what you’re doing.

What has been your actor’s workshop? What were your first film inspirations?

There are so many films and so many actors like Dilip sa’ab to Balraj Sahni. But my first film experience was at Anupam theatre, now PVR Anupam. It was a documentary on white elephants (laughs). That was my strongest memory though not very exciting. I have subsequently watched serious classics. For example, Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam has been one of my favourites. At the same time, I loved Jackie Chan. Yes, the Sherlock Holmes series on TV, with Jeremy Brett, had a deep impact. There were all kinds of stuff but as you grow older, obviously you need to understand cinema and do take it a little more seriously. My father was also somebody who hugely inspired me as an actor and even though he worked largely in television, his roles were so fine and well-crafted.

The same goes for my mother, especially when it came to classical dance. During her performances, she has been exponentially at another level. So what started inspiring me was the skill that they had and the refined movement of that skill. It became something that

I aspired for, the fact that they are so good at it.

I remember attending an acting workshop at NSD conducted by Naseer sir (Naseeruddin Shah) for only a week where I met Randeep Hooda too. I had, at that time, already become an actor and was getting some work, so I thought ki thoda better kar lete hain skills apne aap before kisi ko pata chale ki bohot kharab hai yeh (laughs). As I said, I saw my parents work really hard to be exceptional. It is never just about popularity but about the skill and drill of the craft.

So how do you go with that drill and process your acting skills? Do you research?

I am good with my instincts. I really feel that these days, a lot of research is done by writers and filmmakers. The material is in front of you, you just have to absorb and interpret and that happens once I start shooting.

I stay within that character’s defined zone for that time. Because I feel that you can spend six months doing a film and after you’re out of it, you don’t really know what it was. That happens. So concentrated time works for me.

How do you balance your family and work, now that you’re a hands-on father? As someone who is transiting through changing times, both societally and in cinema, how do you keep it real?

First, I want to express very candidly and honestly that individuality is a huge part of being a youngster today and I have gone through this phase. I have been living alone since I was 22. Even though I was close to my parents, I was living alone. So I am used to this phase of wanting to find myself and being my own person. But it is because of this that I also feel a family is the bedrock of society. You truly understand that when you have it. So that is something I would definitely want to say openly. I can see that people are afraid, unsure and sometimes not even prepared to give so much to something as marriage and a home, but I feel that what you give to it is nothing compared to what you get from it. Whoever I am and what I think is largely governed by my personal life and the space that I have today. Even the actor that I am draws itself from my personal space. My family is my nucleus. Even when there are bits of my life, my daughter Misha, on social media, it is an organic extension of this fundamental truth.