While cities that experimented with free public transport achieved positive results for a while, sustaining them beyond a few years proved to be a problem

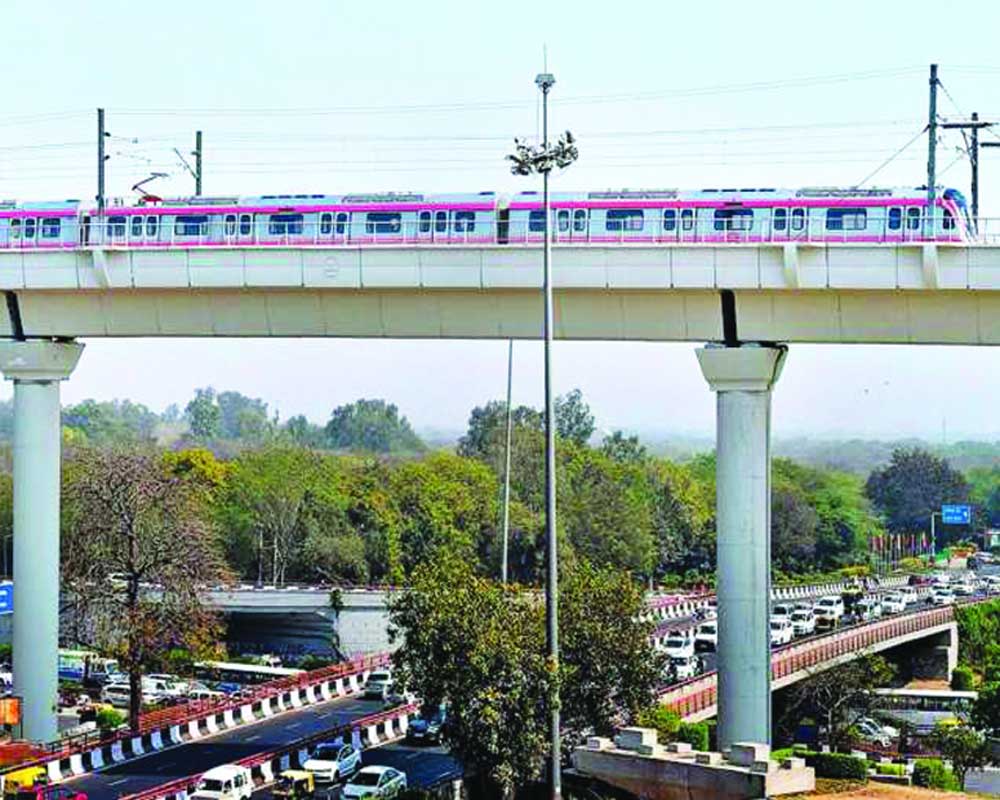

Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal’s announcement on offering free public transport to women has sparked off a debate across the country about the financial performance and pricing of public transport. As cities across the world struggle to keep the Mass Rapid Transit System (MRTS) and other modes of public transport financially viable, scholars and operators alike are trying to arrive at an economically sound formula for operations.

According to an estimate by the Delhi Transport Corporation and the Delhi Metro, women constitute around 30 to 35 per cent passengers in both buses and the trains. This comes to about 14 lakh women per day on the buses and 800,000 women per day on the metro. The Delhi Government is assuming that the scheme will see a rise of 50 per cent in female ridership, resulting in a decrease in the number of vehicles on the city’s roads and improved safety for those vulnerable sections who cannot afford public transport otherwise.

Impact studies in cities that have experimented with a free public transport policy indicate tangible benefits such as higher ridership, less traffic congestion, better air quality, savings on printing, ticket-punching technology and the people engaged in ticket sales. Free public transport promises intangible benefits, too, such as a stronger democracy, higher citizen participation, better liveability and a vibrant economy.

However, it is easier said than done. Cities like Tallinn in Estonia and Châteauroux and Aubagne in France experimented with free public transport in the past and achieved positive results for a while. Sustaining the results beyond a few years, however, proved to be a problem. Also, while the combined effect of free service and happier commuters can significantly increase ridership, public transport can also experience a rebound effect, resulting in crowding and poor service quality due to a large demand response. Such a response can result in a higher tax burden for the transport agency.

The key to operating a free public transport is to identify alternate sources of revenue to finance it. Sustaining a free transport policy in the long-term, especially during times of economic volatility, can be highly strenuous. The city of Châteaurouxin, France could generate returns on public transport in 2003, 2004, 2005 and 2007. However, 2008 onwards, the returns declined. The city of Hasselt in Belgium had to wind up its free public transport policy after a few years as the Government could no longer support its financing.

So, the big question is, can Indian cities afford free transport for their citizens, given the burgeoning population of the country?

Cities in India face a severe shortage of public transport. City peripheries and low-income neighbourhoods often remain unserved and even if a network of buses and local trains and so on exists, the frequency of service is low, rendering it ineffective. Free or otherwise, the absence of public transport results in last-mile connectivity problems for the poor. Addressing the inadequacies of the country’s public transport network will require huge capital investments and considering the amount of expenditure it entails, it could be too much of a burden on the State Governments to then generate funds for operating expenses.

However, the good news is that, though it appears impossible at present, there are solutions worth exploring. Given that State Governments are finding it difficult to provide even partial support in the form of subsidies and grants to public transport agencies, relying on budgetary support to fund a free transport policy seems very difficult at present. Running free public transport may or may not be possible but every city must have at least an affordable transport system. There are a few strategies for long-term funding and cost-cutting that could be explored for achieving this.

Cross-utility subsidy: Although it’s not very popular in the country, cross-utility financing is prevalent in many parts of the world, including Europe and North America.

There are many ways to enforce a cross-utility subsidy like imposing a levy on utility use or cross-subsidising a loss-making utility by a profit-making one. The loss-making transport department of the Brihanmumbai Electric Supply & Transport (BEST), for instance, was, for a long time, cross-subsidised by revenues generated by the profitable electricity department. If implemented in a prudent manner, cross-utility subsidy can offer a long-term solution for funding public transport.

Targetted subsidy: Grants often fail to benefit the desired user groups. So, the solution lies in introducing selective subsidisation for carefully identified beneficiaries. It is a difficult thing to pull off but one can take heart from the fact that over 10 million customers in India gave up their Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) subsidy in response to the Government’s plea. If people are made aware about the purpose of a subsidy, there will be many who will give it up if they don’t require it. At any rate, the Government should explore targetted subsidies to offer affordable public transport to the needy and the vulnerable.

Dedicated transport fund: Many experts have emphasised the need to exempt public bus transport corporations from the motor vehicle tax. For many bus corporations, the operational losses are almost equal to what they pay as motor vehicle tax. While there is a sound rationale behind taxing vehicles that generate huge negative externalities like emissions and congestion, imposing a similar tax on public buses is draconian. On a “per passenger kilometre” basis, public transport is more efficient and causes lower emission and congestion than private vehicles. Moreover, the tax gets directly passed on to the commuters as part of the fares they pay. Foregoing the tax will also make fares more affordable and improve the financial accessibility of public transport.

New performance indicators: There is also a need to develop new performance indicators for evaluating public transport corporations. These indicators must mainstream social and environmental goals. Currently, public transport operations in the country are guided primarily by financial parameters like earnings and cost-per-kilometre. Now, more emphasis needs to be placed on the intangible socio-economic benefits such as time savings, improved productivity, lower congestion and improved livelihood opportunities that public transport enables. Changing the way public transport corporations are assessed will also change the manner in which they operate and the goals they prioritise in service delivery.

While financial performance is critical for operating public transport, increasing the fare is not the best solution. The approach to the problem will change once it is realised that the objective of operating public transport is not to generate revenue but to offer affordable services to citizens. The need of the hour is to find innovative solutions to make public transport affordable for all.

(The writer is Area Convenor, Centre for Sustainable Mobility, TERI)