The collapse of the Knoedler Gallery, New York’s oldest, was a much more protracted and complex process than an ongoing law suit

In Manhattan Federal Court, there’s a trial taking place that has highlighted just how murky the business of art authentication has become.

After suddenly closing in 2011 in the wake of massive lawsuits, Knoedler Gallery and its former director, Ann Freedman, are currently faced with a civil lawsuit by collector and Sotheby’s chairman Domenico de Sole, who thought he had bought an US$8.3 million Rothko from the gallery. It was actually painted by Pei-Shen Qian, a Chinese immigrant living in Queens.

But the collapse of the Knoedler, New York’s oldest art gallery, was much more protracted and complex.

A history of questionable dealings

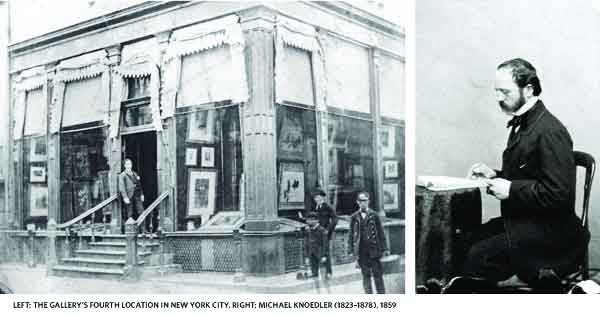

When Michael Knoedler arrived in New York in 1846, the city had virtually no art dealers to speak of. He sold inexpensive prints from Paris. By the turn of the century, the gallery advanced into the field of original old masters.

But the ongoing court case isn’t the first time the gallery has been embroiled in nefarious dealings. In 1931, representatives of Knoedler purchased 21 masterpieces from Russia’s Hermitage Museum for Andrew Mellon in a set of secret sales sanctioned by Joseph Stalin. The works included van Eyck’s Annunciation and Botticelli’s Adoration of the Magi, which sold for roughly $900,000. The deal was brokered by Armand Hammer, an American with close business ties to the Soviet Union.

Nor is the recent case their first brush with forgery. In the 1958 edition of Art News Annual, the gallery took out a full-page ad with a 1948 Matisse that turned out to be a fake.

A gallery reborn

Soon after Knoedler found itself teetering on bankruptcy. In 1971, the gallery was sold for $2.5 million – to their old partner in the Hermitage deals: Armand Hammer.

Hammer appointed his business partner Maury Leibovitz to run the operation. Leibovitz, in turn, hired a well-connected art world figure, Lawrence Rubin, as gallery director.

Leibovitz and Rubin reversed flagging revenues by switching back to mid-century and contemporary art.

Things fall apart

Armand Hammer died in 1990, and his grandson, Michael A Hammer, assumed control of the gallery. When Leibovitz died in 1992, the gallery’s relationship with Neiman deteriorated. Then, in 1994, Michael Hammer dismissed Rubin which caused an exodus of artists led by Rauschenberg.

The gallery needed to find a source of income. Enter: an obscure Long Island gallerist named Glafira Rosales, who represented undiscovered Abstract Expressionist works belonging to an anonymous “Mr. X.” which he was willing to sell below-market prices.

In 1993 the estate of Richard Diebenkorn claimed two drawings from his Ocean Park series were fakes. Without the profits from these sales, however, Knoedler would have likely collapsed.

In fact, much of the argument for Ann Freedman’s culpability in the ongoing trial comes from the unlikely profitability of these sales. Many had achieved resale values five to eight times their purchase price from Rosales.

Yet despite some more red flags — including a Pollock sold in 2002 that the International Foundation for Art Research (IFAR) couldn’t find support for the claimed provenance — Knoedler’s continued to sell works coming from the collection of Rosales’ mysterious Mr. X.

The full scale of the alleged conspiracy, however, became apparent only through two concurrent cases.

One was a Robert Motherwell painting from the artist’s Elegy to the Spanish Republic series sold by Julian Weissman, a former Knoedler employee.

The Dedalus Foundation (which publishes the authoritative compendium of Motherwell’s body of work) first wrote in 2007 that it would be included in the upcoming edition. However, it wrote back two years later to say it would not as the piece had been tested and found to contain materials not yet patented at the time the painting was purported to have been made.

The other case involved another Pollock that Knoedler sold to hedge fund manager Pierre Lagrange with an assurance, apparently, that it would be included in the updated edition of Pollock’s catalogue raisonné. In fact, the artist’s authentication board had been disbanded since 1995. When no major auction house would accept the painting for sale, Lagrange filed a suit in 2011, and the gallery promptly closed.

The biggest indictment, however, may concern the abstract expressionist art movement. The current court case surrounds a Mark Rothko forgery that Art Basel founder Ernst Beyeler described as “sublime.” After all, if a Chinese immigrant in Queens could do them all quite convincingly, one has to wonder how many other abstract expressionist fakes have been bought and sold.

And if a high-profile gallery was willing to sell them, can anyone really trust the authentication process that’s in place – for abstract expressionist works and beyond?