Storytellers Uncle Larry Walsh and Ron Murray tell Sakshi Sharma that Aboriginal people are connected to the modern world as intimately as they are to their roots

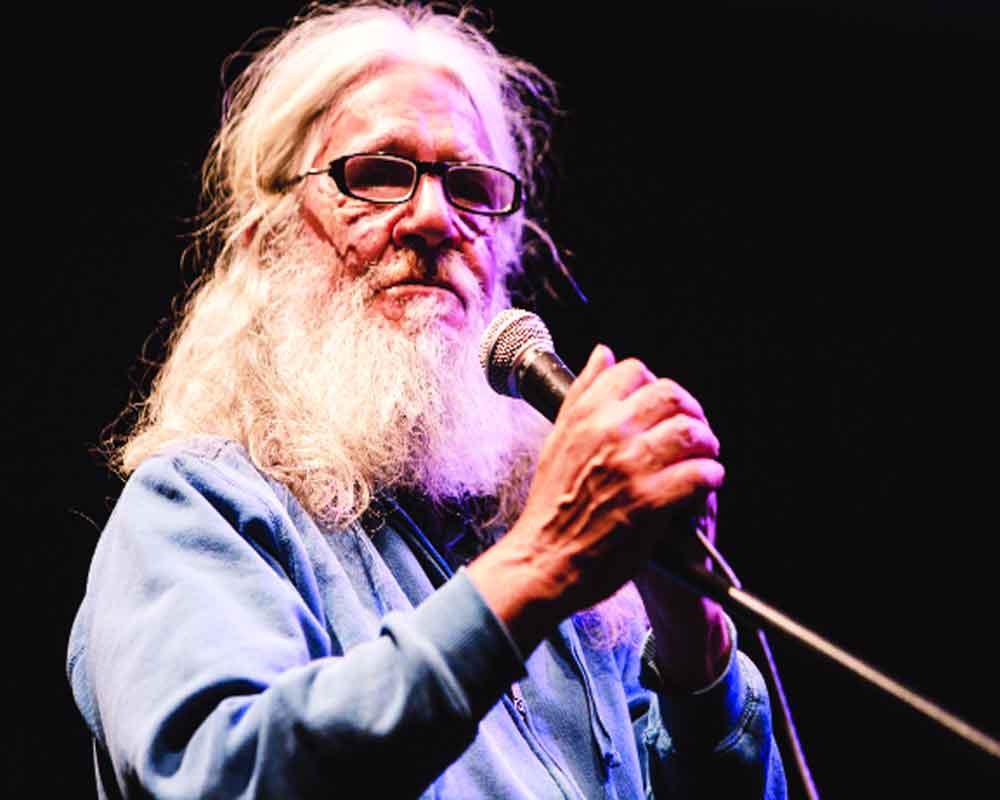

He has a long powder-white hair, tired, blood-flecked eyes, a full white beard, bushy eyebrows and wrinkled blue-veined skin. One can notice his unsteady walk and faded smile with two weak teeth and feeble voice as he holds a cigarette between his crooked fingers and says, “I will just have a smoke and come back.” Meanwhile, I sit there on a rusted bench amid the trees and chirping birds wondering what this unusual style of interview has in store for me.

Uncle Larry Walsh, a local Aboriginal cultural leader, is one of the first indigenous storytellers at the Kathakar Storytelling festival. Inspired by his local community and Kulin ancestral blood connections, he is one of the only seniors in Melbourne who focusses on storytelling, ensuring the cultural continuity of his ancient oral traditions.

While performing 60,000-year-old stories honouring the oral traditions of the Kulin Nations Dreamtime (South Eastern Australia), Walsh presents them through a contemporary lens, illustrating the timeless quality and relevance of these ideas and knowledge to modern day life. Through his stories he wishes to display that Aboriginal people are connected to the modern world as intimately as they are connected to their past.

Talking about the festival, he says, “I hadn’t seen Indian storytellers performing before. It was great listening to them. Though I don’t know Hindi but the voice modulations, the comic timing and the reaction of the audience helped me understand the essence of the stories. We shared our puppetry too.” He adds that he was surprised by a woman who was telling stories in Hindi and English as well. As there was no language barrier, everyone in the hall, including him, understood her.

Storytelling is an art where the narration has to be in a way that the listeners feel connected. They should be able to picturise the incidents while being transported to a different world altogether. Walsh says, “It is a tough but powerful medium of connecting with people. Everyone has stories to tell but not everyone has the right way or art of doing it. For me, it is more about having a rhythm. So, I judge a storyteller on this basis.”

The 65-year old storyteller was not allowed to share all the stories he wanted to. He could only share the stories from the areas that he had permission. He shares that even in ancient times, nobody was allowed to openly discuss Aboriginal tales. “My grandmother narrated some to her children. While doing so, she made sure that no one noticed this because she wasn’t allowed. Later, my uncle told me some that he remembered. When I travelled with him to the hilly areas, he told me stories of each area that we passed by. This helped to build a memory bank.”

Every narrator has a reason why they had come into this profession and stayed. Even Walsh has one. He says, “I loved talking about history and ancient things. So, one day while I was talking about it, my aunt said, ‘when you share your views and knowledge about any subject, it seems as if you are telling a story which one wants to hear more’.” He grins, pauses and adds, “I took that comment so seriously that even after 25 years, I am still telling stories.”

Walsh feels that because he was always interested in reviving the ancient traditions, he was seen as someone who would take it to the future generations. This made everyone share stories with him. Along with this, he also helped communities. So when it was anything around revival, he was asked to join in.

One can clearly see the lines of experience on his forehead. He has witnessed the technology and digital era taking over the world because of which the content and storytelling have changed. And because of this, the essence of storytelling is getting diluted. Walsh agrees: “Earlier we used to tell stories in many folds. Each had many context which were important to the narration. But that is not the case now.”

It’s important to revive stories to keep them alive else the youth won’t be aware of their rich history. “We also describe the natural calamities that had occurred thousands of years ago and their aftermath. It is important for people to know this so that they are always prepared for them. They also need to know what and how their people have faced disasters,” he says.

Walsh particularly loves working with the younger generation as he sees them as the torch-bearers of the society. But it is important for the youth to be interested in the oral traditions. He says, “It gives a sense of pride to them that they know a story which is 20,000 or 60,000 year old. It also helps them to learn important places that are relevant to their history and culture.”

However, the audience wonders about the relevance of Aborigine tales in India. “Many Indian stories, for instance the one about a magician, were similar to our tales. Even your stories describe the forgotten history of India. So, this helped us exchange ideas and learn from each other. Now, I want to call some Indian storytellers to Australia as they were so good that they prompted me to exclaim in disbelief,” he adds.

Another storyteller, Ron is a cultural educator, musician, Didgeridoo maker and a wood sculptor. He is known for performing with Didgeridoo, which is made out of a hollow, native tree called Maali. It is one of the oldest musical instruments in the world which he says dates back to over 25,000 years. The instrument, incidentally burst into the collective Indian consciousness with Dil Chahta Hai (2001) and its popular duet Jaane Kyun.

He mimics the sound of the Kookaburra or the engine of a car. The traditional instrument lends his stories a lilting touch which, he says, enthralled the crowd. As I ask him a Aborigine tale, he immediately runs towards a tree where his Didgeridoo is lying and returns with it. He then plays the instrument and shares how his people formed circles around rocks and danced with the instrument.

Ron also performs around the fire. When I ask him about it, he says, “Fire is a very important subject. For me, it’s related to ghosts and spirits. In ancient times, when there were no matchsticks and people lived in forests, they rubbed stones to create friction and generate fire. A spark in the fire made people believe that the spirit of the forest was listening to the stories.”

A spark of love for stories from ancient times has certainly been lit and people will keep coming back for more.