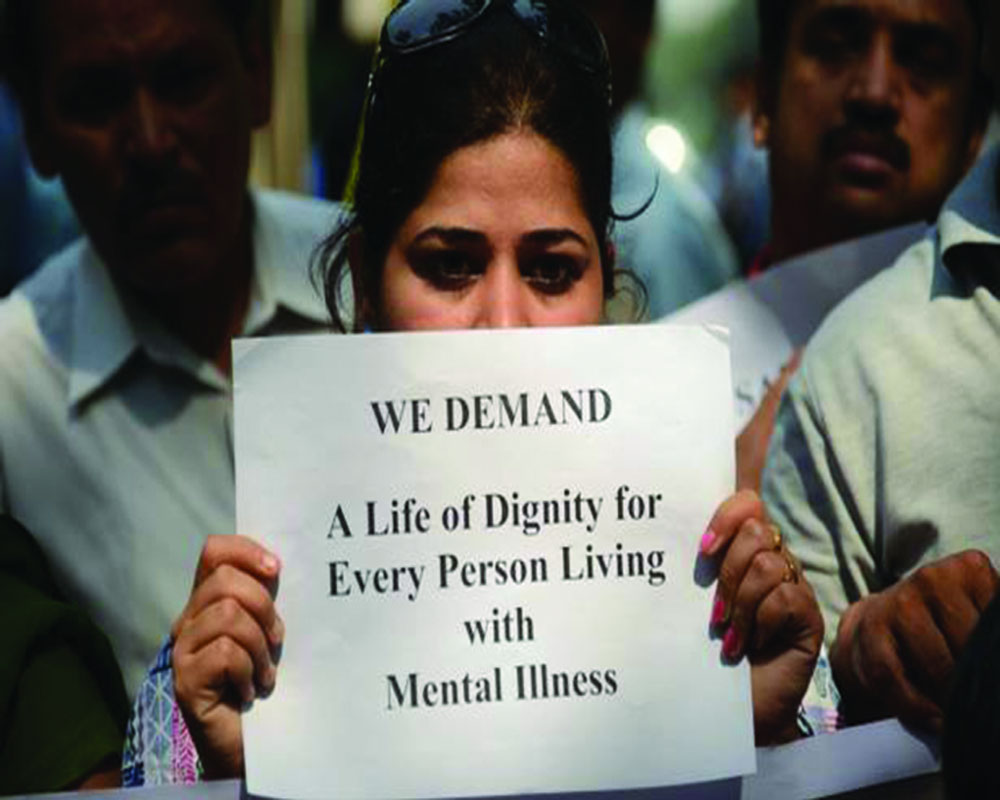

India, like the rest of the world, is now confronted with a brewing pandemic of mental sickness. But we are almost as ill-equipped to handle this crisis as the outbreak

The battle against the Coronavirus, fought with social distancing and enforced isolation, is taking a psychological toll on many of us. India, like the rest of the world, is now confronted with another brewing pandemic of mental sickness. But we need to be aware that we are almost as ill-equipped to handle this crisis as we have proved to be in the handling of the outbreak. As the world commemorates the World Suicide Prevention Day today, it is imperative to understand mental health issues and their impact. Anne Harrington, the pre-eminent historian of neuroscience, says that the medicine and science related to the mind and brain have not come as far as we all would like to imagine or wish.

The death of ambitious actor Sushant Singh Rajput (SSR) in the middle of a pandemic that shattered his professional life and schedule, shook us all, making us realise that we need to work on inner fitness as much as we do on physical well-being. It is a well-know fact that the actor had been on medicines for his mental health issues. At the end of the Central Bureau of Investigations (CBI) probe, if a murder is excluded, then the next question that arises in our minds is: Who killed SSR, the depression or the medicines/drugs he was on? Many of the psychiatry medicines, the “mind fixers”, have side effects that may precipitate or aggravate the very symptoms/disease they are meant to relieve or cure.

For over half a century, renowned psychiatrist Thomas Szasz insisted that illness, in the modern, scientific sense, applies only to bodies, not to our minds, except as a metaphor. A body part or an organ, say, the heart, can be diseased, but to be heartsick or homesick, though real enough, is not to be medically, but only metaphorically, ill. Equally metaphorical, said Szasz, were such supposed mental illnesses as hysteria, obsessional neurosis, schizophrenia and depression. Unlike surgeons and oncologists, psychiatrists don’t have the privilege to peer into a microscope to see the biological cause of their patients’ suffering, which arose, they assumed, from the brain. They are stuck in the pre-modern past, dependent on the apparent mental condition as judged from the outward manifestations to devise diagnoses and treatments.

Challenges to the legitimacy of psychiatric diagnosis forced the profession to examine the fundamental question of what did and did not constitute mental illness. Homosexuality, for instance, had been considered a psychiatric disorder until the seventies, but now it’s accepted as a natural phenomenon in humans and animals. In the late 19th century, researchers explored the brain’s anatomy in an attempt to identify the origins of mental disorders. Such studies ultimately could find no specific anatomical location causing such disease. Researchers those days analysed autopsies of patients, who had suffered from mental illness, but the brain anatomists found that the mental illnesses left no trace in the solid tissue of the brain. Anne Harrington frames this outcome in the Cartesian terms of a mind-body dualism: “Brain anatomists had failed so miserably because they focussed on the brain at the expense of the mind.”

The pathological basis of almost all mental disorders remains as unknown today as it was in the 19th century. It’s unsurprising, given that the brain is one of the most complex objects in the universe. When you follow evolution of psychiatric disorders, you’ll see that in every disease, the treatment came first, often by accident, and the explanation never came at all. Psychiatrists prescribe a range of treatments, though none of them can be sure why any of these biological therapies actually work. Antipsychotic drugs are routinely prescribed to depressed people, and antidepressants to people with anxiety disorders. However, one needs to be aware that the medications have risks that outweigh the benefits for more patients than you probably realise. As antidepressants became more commonly prescribed for anxiety and obsessive compulsive disorder, the reports of patients’ suicidal thoughts and actions became more worrisome to physicians and family members.

In 1990, Harvard researchers reported that six patients had developed intense and violent suicidal preoccupations soon after starting to take fluoxetine (Prozac), which had been approved for the treatment of depression only two years earlier. The warning adds that patients and families must be advised of the risk, and that the patients taking antidepressants must be closely observed for worsening symptoms. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) admitted in 2007 that the SSRI (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) group of drugs (common names used Prozac, Zoloft) can cause madness and that the drugs are very dangerous. “Families and caregivers of patients should be advised to look for the emergence of such symptoms on a day-to-day basis, since changes may be abrupt,” stated the report. Researchers in a few other studies also found evidence that individuals taking antidepressant medication seem to be at even higher risk of suicide than individuals whose depression is easing for other reasons. That controversy has not yet been completely resolved.

Psychiatry remains an empirical discipline, its practitioners as dependent on their (and their colleagues’) experience to figure out what will be effective or not. Sigmund Freud commented that there was an intimate connection between the story of the patient’s sufferings, his upbringing and social conditions, the severity and type of mental trauma undergone and the symptomatic manifestation of his/her illness. Freud also stated that case histories of a psychiatric patient should read like short stories without the serious stamp of science. In 1954, the FDA, for the first time, approved a drug as a treatment for a mental disorder: the antipsychotic chlorpromazine (marketed with the brand name Thorazine). The pharmaceutical industry vigorously promoted it as a biological solution to a chemical problem. By 1964, some 50 million prescriptions had been filled in the US. Next approved were the sedatives in 1955. Meprobamate was hailed as a “peace pill” and an “emotional aspirin.” Within a year, it was the best-selling drug in America, and by the close of the fifties, one in every three prescriptions written was for meprobamate. An alternative, Valium, was introduced in 1963 and became the most commonly prescribed drug in the US until 1982.

One of the first drugs to target depression was Elavil, introduced in 1961, which boosted available levels of norepinephrine, a neurotransmitter related to adrenaline. Then the focus shifted from norepinephrine to the neurotransmitter serotonin, and in 1988, Prozac appeared, soon followed by other SSRIs. In America, the final decade of the 20th century was declared the “Decade of the Brain.” But, in 2010, the National Institute of Mental Health reflected that the initiative hadn’t been able to move the needle in reducing suicide rates or overall recovery of mental illnesses. Anne Harrington calls for an end to triumphalist claims on treatment of mental illnesses and urges a willing acknowledgement of our limitations in diagnosing and treating the mentally diseased.

Having stated the above, it’s important to reiterate that although psychiatry is yet to find the pathogenesis and specific medicines of most mental illnesses, it’s useful to know that medical treatment is often beneficial even when pathogenesis remains unknown. This is very comparable to the case of peptic ulcers where we now know that stress doesn’t cause ulcers but it can exacerbate the symptoms and hence controlling stress can help a patient. This was seen in other pathological conditions where medical advice and treatment of a disease helped patients much before the discovery of the cause/pathogenesis; for example in AIDS, advisories of safe sex practice had helped even before the causative agent HIV was discovered and drugs developed.

The search for pathogenesis in psychiatry continues. Geneticists may one day shed light on the causes of schizophrenia, but in all likelihood, it would take years for therapies to be developed. Recent interest in the body’s microbiome has renewed scrutiny of gut bacteria; it’s possible that bacterial imbalance alters the body’s metabolism of dopamine and other molecules that may contribute to depression.

More importantly, we’d do better not to set so much store by the idea of a single key solution to mental sickness. It’s more useful to think in terms of cumulative advances in the field by being more knowledgeable about the range of treatments available and lifestyle recommended. Plus there have been other approaches such as cognitive-behavioural therapy, which was propounded in the seventies by psychiatrist Aaron Beck. He posited that depressed individuals habitually felt unworthy and helpless, and that their beliefs could be “unlearned” with training. An experiment in 1977 showed that cognitive behavioural therapy outperformed one of the leading antidepressants.

Words are another powerful tool in healing of the mind as they can alter, for better or worse, the chemical transmitters and circuits of our brain, just as drugs or electro-convulsive therapy can. We still don’t fully understand how this occurs. But we do know that all these treatments are given with a common purpose based on hope, a feeling that surely has its own therapeutic biology.

(The writer is an author and a doctor by profession)