Fractured Forest, Quartzite City: A History of Delhi and Its Ridge by Thomas Crowley tells the tale of the Ridge, which resonates far beyond the boundaries of Delhi. The Ridge offers a crucial vantage point for viewing these historical and geographical interconnections. Its trees can't be separated from the stones below them, nor the cities that rose and fell around them. Only with this perspective does a clear picture of the Ridge — and Delhi as a whole — emerge. An edited excerpt:

The British had placed a legislative stamp on a process they had started more subtly decades earlier: the assault on pastoral livelihoods and commonly held village land, and the replacement of such land with individual, salable plots interspersed with government-controlled enclaves.

From Sacred Grove to Real Estate

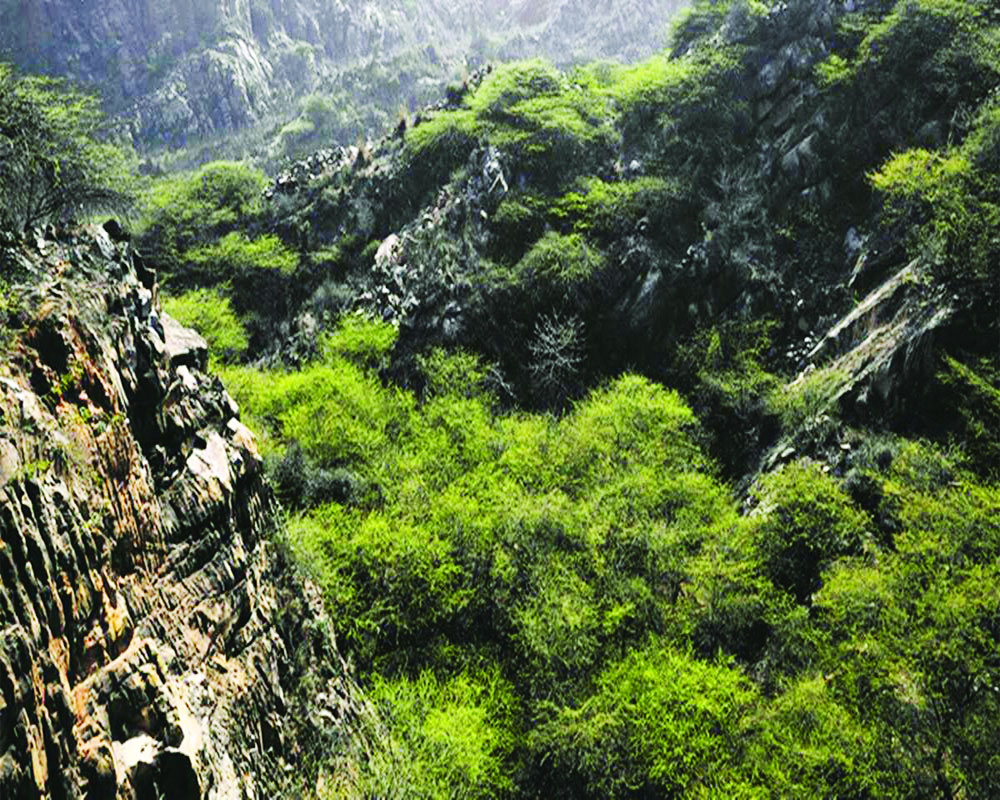

This process, which started on the Northern Ridge, took a long time to spread southwards; indeed, the story is still unfolding at the far reaches of the Southern Ridge and beyond. Here, one can find traces of older ways of life, of the “reservation of wood-producing land... generally connected with religion”, which the British found when they first entered the region. The most remarkable example of this is the sacred grove of Mangarbani. The grove technically falls in Haryana, outside the bounds of the National Capital Territory of Delhi (a clear- cut boundary that owes its contours to the British). Officially it is not part of the Delhi Ridge. But it is on the Aravallis, so its underlying stones and soil are identical to those of the Ridge.

What grows out of this stony soil has amazed observers from Delhi. Mangarbani is densely forested, and it is full of trees that have long disappeared from the Delhi Ridge, most notably the graceful, hardy dhau tree. The thriving forest is part of common lands shared by the three villages of Mangar, Bandhwari and Baliawas, which are dominated by the Gujjar community; these villages maintain Mangarbani as a sacred grove in honor of a holy man named Gudariya Baba who used to roam these parts.

The very existence of such a remarkable ecosystem in the midst of three Gujjar settlements neatly refutes the argument originally put forward by Maconachie and Beadon, and still echoed today by some government officials and environmentalists: that villagers, especially those with strong pastoral traditions, like the Gujjars, do not care about trees, and land must be taken away from them and vested in the government if it is to be protected.

Instead, Mangarbani suggests another lesson: that the ecological behavior of pastoralists is molded by the larger systems in which they are ensconced. For example, during Mughal times, the Gujjars living close to Shahjahanabad put excessive pressure on their commons because of urban demands for meat and milk; meanwhile, the Gujjars of Mangarbani, much further away from city influences, left a more balanced ecological footprint. This remained the case during British rule as well, despite the compulsions of British land settlement efforts and despite pockets of quarrying. But, over the past several decades, Mangarbani has increasingly been drawn into the orbit of a rapidly expanding Delhi, a trend that has threatened the survival of the grove.

Regular readers of Delhi newspapers may be familiar with this story. On almost a weekly basis, one reads about a new threat to the old forest. Or about threats to people in the forest. By far the most dramatic headline came on 31 March 2014: “Birdwatchers Thrashed at Mangar Forest”.

The events described in the article are a combination of the disturbing, the tragic, and the absurd, a mix that characterizes much of the Delhi region in an era of runaway growth. The birdwatchers were from nearby Gurgaon-not too long ago, a sleepy farming village and now an urban hub conjoined to Delhi and filled with automobile factories, multi-national corporate offices, small-scale garment industries, and a seemingly endless expanse of malls. (The city was renamed Gurugram in 2016, a Hindu nationalist nod to the Mahabharata sage Guru Dronacharya, who supposedly lived in this area thousands of years ago. However, for the sake of avoiding anachronisms, I will stick with “Gurgaon”, the name that was current when the following events took place.)

The birders had gone to Mangarbani to spot winged wildlife in the native forests of the grove. When the first car reached the grove, they came upon a man who said he was the priest at the local temple; he wanted to know what they were doing there. Things got a bit heated, and the priest took out his phone and made a call. Within minutes, a group of young men sped onto the scene in a jeep. They jumped down, armed with sticks and iron rods, and attacked the birdwatchers, a group which included an elderly woman and a young child. The attackers fled, though, when the rest of the birdwatchers, another four or five carloads, arrived on the scene.

The priest was later arrested, along with some of the assailants. Now, though, they are all out on bail, as the rusty machinery of the justice system does its agonizingly slow work. Many of the news reports after the attack asserted that the priest has played a central role in real estate transactions in the area. The British may have been the first to introduce the idea of land as a commodity in the Delhi region, but now, centuries later, the idea has become common sense. It is embraced with gusto by the wide range of players that make the real estate industry tick, a group that, apparently, includes a temple priest and his hired muscle.

Real estate is now the shadow that hovers, unavoidably, over Mangarbani and the three villages that surround it. This, though, is a relatively recent development, and it has gained traction due to the changing role of the Gujjar landowners in the villages. The fact that Gujjars are the dominant landowners suggests that, in this area at least, they long ago made the transition from nomadic tribe to settled community. Pastoralism still plays a role here, but it has long been complemented by agriculture, and it has taken place around fixed village settlements. And Gujjars have integrated into a caste-based village structure, finding themselves in a powerful position within the local hierarchy.

The complexity of the caste system is in full view with the Gujjar community. In most states in India, Gujjars come under the administrative category of Other Backwards Classes (OBC), which puts them below the traditionally “high” castes, but above Dalits (administratively: Scheduled Castes or “SC”) and tribals (Scheduled Tribes or “ST”). It also makes them eligible for a range of reservations made available by the state. But this cut-and-dry state-imposed category hardly gets at the nuances and the internal differences within Gujjar communities. In some parts of India, especially in the Himalayan foothills, Gujjars still live a more tribal, nomadic existence, with little integration into settled caste systems; however, in other contexts, including Mangarbani, they are not only integrated, they are also the most powerful community in a given village.

While OBC may, then, be a wholly inadequate way to describe Gujjars, the designation is still vitally important, given its link to reservations. In some cases, Gujjars have demanded a lower status, so that they have access to more state benefits. These are the exigencies of modern-day caste politics. While the impulse behind reservations is a deeply progressive one-to provide support and opportunities to groups that have historically been exploited and marginalized-their application must deal with the messy terrain of competing communities, internal discord, and intersecting layers of privilege and power.

Such complex dynamics often lead to explosive results. In 2007, in the state of Rajasthan, a group of Gujjars began to agitate for the inclusion of Gujjars as a Scheduled Tribe (ST), in a sense a step “down” from OBC, but one which would provide them with more state support. As the protests gained momentum, they triggered state repression. Within a span of four days in May 2007, police opened fire on four different groups of protesters, in conflicts which left 25 Gujjars and one policeman dead.

In early June, the protest turned national, as Gujjar groups from around the country descended on Delhi and other major cities, including Jaipur and Ahmedabad. In a remarkable show of community strength, the protesters successfully cut off all road access to Delhi, effectively blockading the national capital. While the agitation was largely non-violent, some protesters set fire to buses and trains. For the elite of Delhi, this destruction of property and interruption of their everyday life could not be countenanced. All the slurs and all the urban disdain toward Gujjars, from Babur to the British, were dredged up. A municipal councilor in Delhi is on the record saying that, for Gujjars, “killing is in their blood”. Protests continued the next year, with 38 more Gujjars shot down by police. The agitation only stopped when the government agreed to give Gujjars reservations, not as a Scheduled Tribe, but as a Denotified Tribe-the official post-colonial term for groups that the British had dubbed Criminal Tribes.

At the height of the agitation, protesters from Rajasthan got strong support from leaders of Gujjar-dominated villages in the Delhi region, who both benefit and suffer from their proximity to state power. Their strength at the village level gives them significant pull in local elections, but despite that they cannot compete with the real power players of the capital. Economically, too, they have benefited from the ever-expanding markets of Delhi, but, except in rare cases, they have not found a place at the table of the city's elite.

The traditional ruling classes in Delhi still see Gujjar-dominated areas as a backwards hinterland, even though, with the expansion of the capital, they are often right in the midst of the urban sprawl. If not physically, they are still metaphorically on the edge of an urban zone that houses a far more powerful set of elites. And it is increasingly not just an Indian elite housed in the Indian capital, but an international elite housed in the multinational offices and luxury high-rises of Gurgaon. This is the larger context in which the Mangarbani drama has played out, as the sacred grove is being inexorably pulled into the capital's sphere of influence.

Excerpted from Fractured Forest, Quartzite City by Thomas Crowley, jointly published by SAGE Publications and Yoda Press under the Yoda-SAGE Select imprint