The recent killings in Kashmir by Pakistan-backed terrorists remind us of what India would have been enduring had there been no Partition

Who wanted Partition? Who needed Pakistan? Certainly, the Khoja, Memon and Bohri businessmen did. They preferred competing with the Punjabi farmer than the Parsis and Banias, Marwari, Gujarati, Chettiars or whichever other traditional trading communities in India. The Habibs, for example, were big grain traders in Bombay. Their junior partner Ratanlal Gandhi once asked the senior Habib why they financed the Muslim League when all their business and property was in and around Bombay? Habib’s answer to Gandhi was that it was much easier to flourish ag`ainst farmers than businessmen banias.

Others keen on Partition were the radical Muslims, wherever they were in India. An educated League leader of Madras — Mohammed Ismail — was a leading supporter not only of Partition but also an exchange of population, which meant that all Muslims ought to go to Pakistan and non-Muslims to remain in India. Ismail himself did not leave Madras. Yet another group of supporters were the students, past and present of Aligarh University which was described by M.A. Jinnah as “the arsenal of Pakistan”. For the rest, Muslims were interested but were unsure and therefore lukewarm. Punjab had a Muslim majority with a Muslim Premier and ruled by the Unionist Party led by Sir Sikander Hayat Khan and his successors. These leaders saw no future in Partition as Punjab enjoyed Muslim rule with the whole of the Indian market freely available to their province.

Similarly, Bengal was in two minds and not clearly for Pakistan. One, to support Partition or to follow the reasoning of Punjab; two, to have a united Bengal as a third separate dominion, apart from Pakistan and India. Sir Abdul Rahim, Fazlul Rahman and Sarat Bose met several times to discuss the issue. Jinnah quietly supported the idea as did the Communist Party of India. The truth was no one could visualise the concept and shape of Pakistan. Not even Jinnah; he retained his magnificent bungalow Marble House on Malabar Hill with the intent of spending his winters there. No one foresaw that relations between the two dominions would be perpetually hostile.

Hindus abhorred the idea of their motherland’s division. Visionaries like Dr BR Ambedkar and Dr Munje of the Hindu Mahasabha realised that the coexistence of the two communities was difficult, and therefore not beneficial. Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and Jawaharlal Nehru came to realise this truth in 1946 when widespread rioting began in August of that year. Punjab had witnessed bloodshed and looting but elsewhere it was business-as-usual. Jinnah was himself not a committed Muslim. His grandfather had converted to the faith led by Sir Aga Khan called Ismaili Khojas. This denomination was declared by the Bombay High Court in 1861 as half Muslim and half Hindu because of its inheritance laws. The family continued to call themselves Jinnahbhai. It was in England, where he was studying to become a barrister that he slightly altered his surname and passport to Jinnah; the ‘bhai’ was dropped. He enjoyed pork sandwiches as well as a sun-downer (whisky) on most evenings.

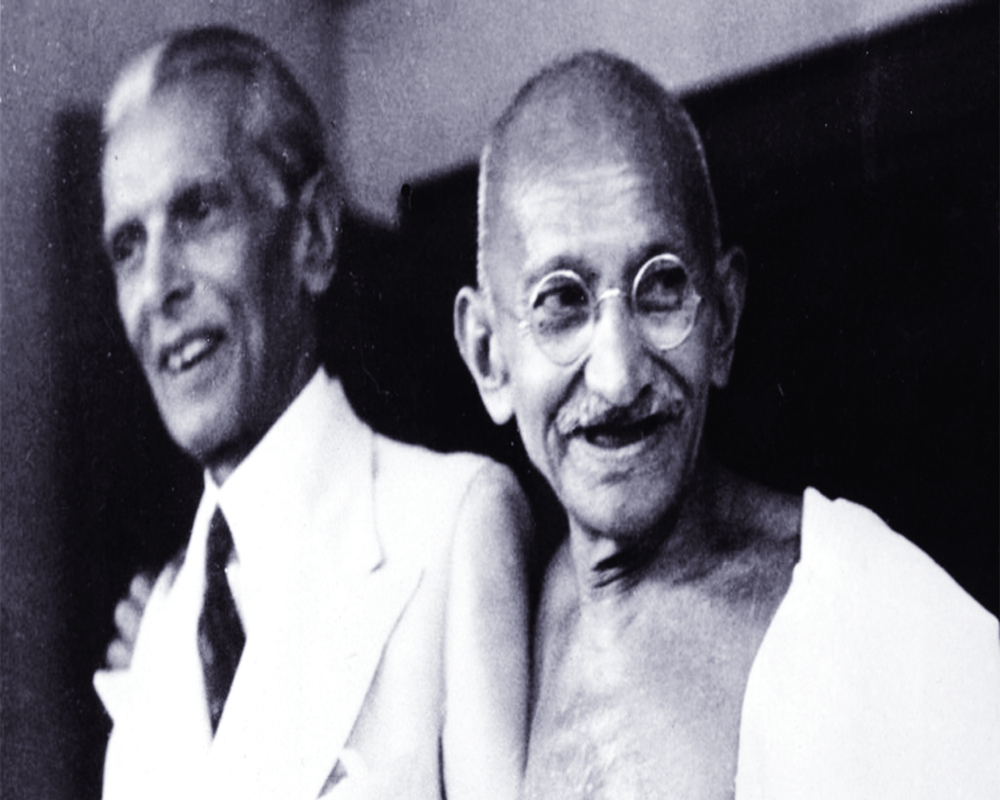

Jinnah knew the cards could be loaded against him. Dead against the grain of his constitutional nature, he ordered the Great Calcutta Killing on 16 August 1946, in the hope that the riots would be retaliated against and spread in the country. Killings in Punjab alone were not sufficient. Moreover, time was running out for him. He either knew or suspected that his lungs were infected with tuberculosis (TB), which until the post-World War II period, was a fatal disease. And sure enough, TB took Jinnah’s life in September 1948. He had to settle scores with Gandhi, first for resorting to taking politics to the streets and villages (which Jinnah could not cope with), and later in 1928, ignoring him at the Calcutta session of the Congress. Jinnah kept avoiding the prefix ‘Mahatma’ and addressing Gandhi as ‘Minister’! The audience did not let Jinnah speak unless he addressed Gandhi as Mahatma. There must have been similar other incidents before 1928. Jinnah had to deliver revenge to Gandhi and began with riots to which the Mahatma had no answer except touring the affected areas and conducting prayer meetings. Nor did he have a counter-strategy. Even Patel, Nehru and others in the Congress couldn’t think of how to counter the League. Non-violence could not cope with brutality and violence.

Jinnah was more a brilliant advocate than a leader. He is reputed to have suits tailored at the famous Saville Row in London but until he was elected the life president of the Muslim League in 1935, he had no chudidar-pyjamas nor sherwanis (essential Muslim attire) as his brother and my grandfather’s dear friend Ahmed told the latter. The brothers did not know how to perform namaz. As Ahmed told my grandfather, the brothers were culturally more Parsi and less Muslim.

(This is part one of a series on Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s role in India-Pak Partition.)

(The writer is a well-known columnist, an author and a former member of the Rajya Sabha. The views expressed are personal.)