Gandhi foresaw the flaws in elections, long before independence. Today’s youth must rediscover that vision to revive a nation straying from its founding ideals

The 20th century was, along with great strides in science and technology, World War I and World War II, also the witness of liberation movements, social reforms, democracies taking root, and —most importantly —the emergence of high aspirations, hopes of progress and development in practically every newly liberated country.

There were great expectations for the creation of a world of peace, harmony, social synchronisation, and religious amity. Gandhi, Mandela, Martin Luther King Jr, and many others on the political side, along with scientists like Einstein, Niels Bohr, and several leading personalities on various fronts, ignited a picture of a beautiful, better, and harmonious world.

The UNO (now UN) was created and was projected as the global decision-making body that would be morally and ethically equipped enough to prevent hatred, violence, and wars. There would be social, moral, and ethical emancipation, and inhuman practices like apartheid, untouchability, and racial and religious discrimination would vanish from the face of the earth. This was the general perception also during the Indian freedom struggle. Unfortunately, the dawn of independent India was swathed in bloodshed, hatred, violence, and terrible loss of human life. India suffered immensely in partition. Worst was the distrust generated between the two major communities — the removal of which has certainly impacted the pace of India’s progress.

There were challenges of poverty, illiteracy, lack of resources, and many others. But hopes did not diminish at any stage. They remained high not only in India but among the people of all the exploited and humiliated nations that had been squeezed for centuries by the inhuman colonial regimes all over the world, particularly by the Europeans. In India, the common man perceived a system of governance that would be free from corruption, infliction of humiliation in Government offices, and where the police would no longer be a dreaded entity. How could our own people in routine Government jobs exploit us when they would be working in a Government headed by our own people? People had full faith in the sincerity, honesty, and integrity of their leadership. In India, expectations were extremely high: once we were a free nation, there would be no corruption, no injustice, no humiliation or discrimination on the basis of caste and creed — and, most importantly, no untouchability; no ban on entry into temples or denial of movement on certain roads. Who could have envisioned the future of India in greater depth than Mahatma Gandhi? In a letter he wrote in 1922, he envisioned the realistic situation that was to unfold once independence was achieved: “We should remember that immediately on the attainment of freedom, our people are not going to secure happiness. As we become independent, all the defects of the system of elections, injustice, the tyranny of the richer classes, as also the burden of running administration, are bound to come upon us. People would begin to feel that during those days, there was more justice, there was better administration, there was peace, and there was honesty to a great extent among the administrators compared to the days after independence. The only benefit of independence, however, would be that we would get rid of slavery and the blot of insult resulting therefrom.”

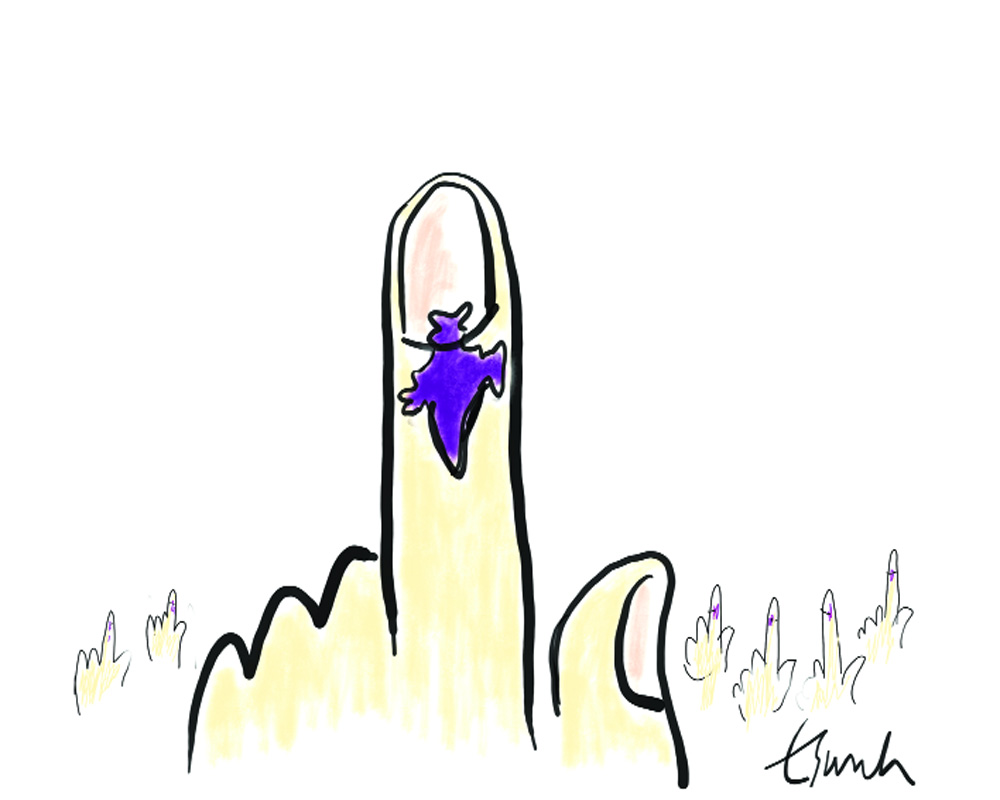

Further: “But there is hope, if education spreads throughout the country. From that, people would develop from their childhood qualities of pure conduct, God-fearing nature, and love. Swaraj would give us happiness only when we attain success in the task. Otherwise, India would become the abode of grave injustice and tyranny of the rulers.” I could never properly comprehend the first one of the above four: defects of elections! How could he talk of the defects of elections in 1922? His apprehension has proved most accurate on this count, and it is impacting the other three just as menacingly. Having gone through numerous elections at the national, state, and panchayat levels, it has become fully clear to one and all that democratic functioning — and reaping its fruits judiciously — requires elections to be conducted in a transparent manner with honesty and integrity, in a purely sound moral and ethical environment.

The nation has repeatedly witnessed how political parties focus attention on openly attempting to create their own clusters of people on the basis of all that was not expected of them by the Constitution of India, and in fact, was clearly prohibited.

The caste combinations, communal angle, regional and linguistic appeals to the voters are being openly practised. The rise of such practices began to flourish only after the dilution of Gandhian values became visible all around, after around two decades of independence. Luminaries like Sardar Patel, Dr Rajendra Prasad, Lal Bahadur Shastri, Dr Bidhan Chandra Roy, and Pandit Govind Ballabh Pant had gone. The generations of young leaders had witnessed that winning elections was the first step towards power, authority, perks, and privileges — and finally, assets and the rise of their near and dear ones. Drifting towards that was not tough. Gradually, they witnessed that power meant personalised economic blooming, and law — exceptions apart — could not touch you once you had held positions of power.

My keenness to understand this transformation — and how Gandhi could predict it — led me to the privilege of interacting with several fortunate persons who had worked with him in their younger days. They told me two things. Firstly, he had studied the British election system very carefully and thoroughly. Secondly, he understood the psyche of Indians very well. The British, as a part of their unwritten policy, permitted the “universalisation of corruption” in the lower administrative Government positions, including judiciary, police, and administration. These two, taken together, gave him a very clear futuristic picture. Now it is widely understood how he could visualise what we are witnessing today in practically every election. Every Indian knows what the “defects of elections” are.

I had the privilege of listening to Pandit Nehru waving at the admiring public from the train in Hardoi during the 1952 elections, as a nine-year-old. It was only by the third general election of 1962 that I understood what it really meant — and how it ought to be conducted.

By this time, some of my university friends had devoted considerable time and energy to understanding politics and political ideologies, and some had even acquired membership of certain political parties.

There was tremendous respect for individual leaders — they had given their all but had snatched nothing from the people for themselves. This was so very well presented in the Lok Sabha by Acharya JB Kripalani while presenting the first no-confidence motion against the Nehru Government after the Chinese invasion and the routing of the Indian armed resistance — and, more importantly, the total dismantling of the non-alignment policy, as well as India’s China policy. Kripalani referred to a statement by ex-Congress President UN Dhebar, who had publicly stated that our Plans had made “the rich richer and the poor poorer.”

He went on to state that the Prime Minister accepted that the rich had become richer but refused to accept that the poor had become poorer. Where do we stand today on these counts? If 800 million people need free ration, their life is certainly deficient in self-respect. Another former Congress President, taking part in the debate, was Purushottam Das Tandon, whom Pandit Nehru never liked because of his admiration for and adoption of Indian cultural traditions. He also highlighted the menacing presence of corruption and its rise. He said openly that within the Congress Party, there were people who had no assets at all and were now multimillionaires. It is high time that the millennials — completing their education and ready to take over the reins of the nation shortly — delineate and redefine their role and responsibility to the self, society, community, and the nation.

(The author works in education, religious amity and social cohesion)