In today’s digital world of misinformation and fleeting outrage, Gandhi’s model of principled media — anchored in trust, restraint and purpose — offers a timeless blueprint for using technology to serve truth, not trends

On June 4, 1903, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi launched The Indian Opinion in South Africa, a publication that became a vital tool in his struggle against racial injustice. As detailed by Ela Gandhi in her book, “Mahatma Gandhi and the Media — The Indian Opinion†a publication of the National Gandhi Museum, New Delhi, the seeds of this resistance were sown on June 7, 1893, when Gandhi, despite holding a valid first-class ticket, was forcibly ejected from a train at Pietermaritzburg due to his race.

That freezing night in the station’s waiting room marked a turning point; he resolved to stay and resist injustice instead of returning home. He also telegrammed the railway manager, urging corrective action against such discriminatory conduct. Ela Gandhi writes, “On that night, he rejected the idea of abandoning his case and immediately returning home to a life of dignity and respect. He rejected the idea of succumbing to the insults and accepting them as a way of life in South Africa. He decided instead to stay on and confront and transform the racist systemâ€.

His activism in South Africa spanned over two decades (1893-1914). During this period, he developed and refined his unique philosophy of non-violent resistance, which he termed “Satyagraha†(truth-force). He organised mass protests, boycotts, and civil disobedience campaigns against discriminatory laws, such as the Black Act (which required Indians to carry registration certificates) and the £3 poll tax (In 1913, the South African Government introduced a £3 tax on Indians, (mainly those who had completed their indentured labour contracts).

These struggles often led to (direct) confrontations with the authorities, and Gandhi, along with thousands of other Indians, faced numerous arrests and endured harsh prison sentences. His imprisonments — further drew attention to unjust laws through non-violent means — and were a deliberate act of civil disobedience for a righteous cause, further solidifying his resolve to fight injustice.

Ela Gandhi notes that Gandhi had “Written hundreds of letters to the press about the irking racism and the various injustices suffered by South Africans. He wrote about the wretched conditions of service that the indentured workers were subject to in South Africa. He produced the famous green pamphlet to discourage Indians from being lured into indenture by false stories and promisesâ€.

Mahatma Gandhi’s strategic use of alternative media was both innovative and deliberate. Deeply conscious of the press’s influence, he also recognised the ethical responsibilities inherent in journalism. As Ela Gandhi notes, “He was also aware of the responsibility that a journalist carried. As a writer or journalist, he constantly exercised discipline over himself to ensure that his reporting was balanced.†The persistent injustices faced by the Indian community in South Africa, along with the imperative for organised resistance, prompted Gandhi to launch ‘The Indian Opinion’. Recognising the inadequacy and bias of the white-owned press, he envisioned a medium that would serve not only as a newspaper but also as a pedagogical tool for disseminating the principles of Satyagraha. It became a critical platform for mobilisation and dialogue, anchoring the nascent Indian civil rights movement.

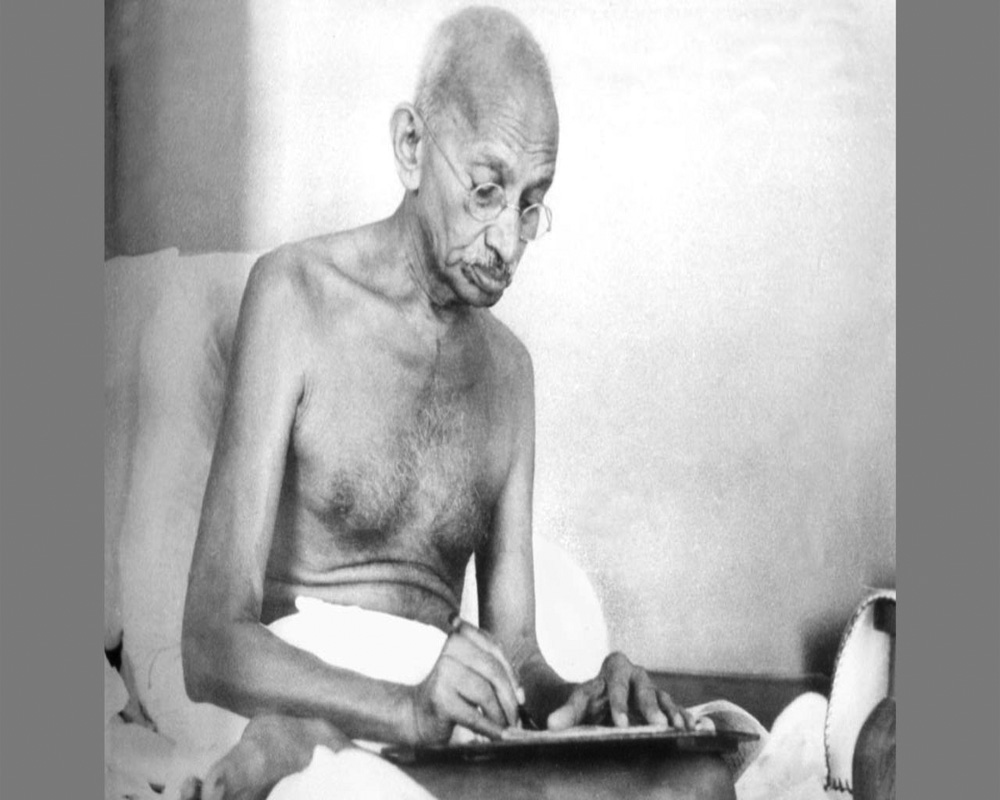

‘The Indian Opinion’ began as a bilingual (later trilingual and quadrilingual) weekly, published in Gujarati, Hindi, Tamil, and English. Its primary objective was to articulate the grievances of the Indian community in South Africa, combat racial discrimination, and foster unity among diverse linguistic and religious groups. Mahatma Gandhi himself meticulously managed its production, writing a significant portion of its content, editing, and even doing manual labour at the press. The paper reported on legal cases, documented instances of injustice, provided educational content and served as a forum for community discussions. Through ‘The Indian Opinion’, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi didn’t just report the news; he shaped it, guiding his readers towards a deeper understanding of their collective plight and the imperative for non-violent resistance, and, simultaneously, Gandhi’s evolution as a leader.

Today, in a world grappling with the rise of divisive narratives and the proliferation of ‘fake news,’ ‘The Indian Opinion’s’ commitment to truth and ethical communication remains profoundly relevant. The digital age has democratised information but has also unleashed a torrent of misinformation, making the discerning reader an endangered species. Imagine Gandhi in the 21st century, armed not with a hand-cranked printing press but with a smartphone.

Mahatma Gandhi might have leveraged social media platforms to disseminate his message in an era of instant gratification and viral content. His iconic quotes could become powerful memes, his calls to action amplified through trending hashtags. However, he would likely approach these tools with extreme caution, prioritising authentic engagement over superficial popularity.

He would use social media not for self-promotion, but for genuine community mobilisation, echoing the words of the Canadian philosopher Marshall McLuhan, “The medium is the message.â€

For Gandhi, the message was always truth and non-violence, and the medium would be moulded to serve that higher purpose. Just as ‘The Indian Opinion’ served as a hub for organising protests and passive resistance campaigns, a modern-day ‘Indian Opinion’ would perhaps be deeply embedded in online activism. It would facilitate virtual meetings, organise digital petitions, and livestream acts of non-violent civil disobedience.

Going forward with what Marshall McLuhan had said, Gandhi would not have succumbed to popularity metrics like ‘likes’ or ‘followers’. Instead, as historian Ramachandra Guha in his book ‘Gandhi Before India notes, Gandhi “was never interested in public applause… he was interested in public awakeningâ€.

Gandhi’s commitment to self-sufficiency and ethical production was evident in ‘The Indian Opinion’s’ operation. He believed in local control and minimising reliance on external, often exploitative, systems. In today’s tech landscape, this translates into a powerful critique of centralised digital platforms and data monopolies.

Mahatma Gandhi might have advocated for data privacy — as it is one of the greatest dangers people are facing. Further, going by his ‘dharma’ (righteous principles), Mahatma Gandhi would have advocated for ethical algorithms, transparent data practices, and the responsible use of artificial intelligence (AI), while cautioning about the dangers of the addictive nature of social media.

American media theorist Evgeny Morozov (2011) argues that online activism often gives a false sense of accomplishment — ‘clicks have replaced commitment.’ Mahatma Gandhi would challenge this hollow activism and call for real-world consequences. “It is not enough to be passively good; we must be actively good,†he once wrote (Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, Vol. 27, p. 164). ‘The Indian Opinion’ of the 21st century would, therefore, focus on ‘converting online energy into offline results’. Today’s journalists often find themselves caught between TRPs, clicks, and ethical compromise. A 2020 Reuters Institute report lamented the declining public trust in mainstream media globally. Gandhi’s ‘Indian Opinion’, however, would choose ‘trust over traffic’.

If the ‘charkha’ (spinning wheel) was Gandhi’s symbol of resistance and regeneration in the 20th century, the smartphone — used mindfully — could become its 21st-century equivalent. Mahatma would strongly advocate for its use with restraint, truth, and compassion.

Last, but not the least, Mahatma Gandhi did not romanticise suffering, nor did he glamourise technology. He was pragmatic yet principled. His digital philosophy would be grounded in Satyagraha — not just in ‘content’, but in ‘conduct’. His “The Indian Opinion†served that purpose.

(The writer is programme executive at Gandhi Smriti Sansthan. Views expressed are personal)