The roots of monastic education in India trace back to ancient religious and philosophical traditions, particularly within Buddhism. From the 5th century BCE, Buddhist monasteries, or viharas, emerged as structured centres of learning. Initially seasonal retreats for meditation and study of the Buddha’s teachings, they evolved into permanent institutions offering systematic education in scriptures, ethics, logic, and philosophy.

Renowned centres such as Nalanda, Vikramasila, and Takshashila became magnets for scholars across Asia, embodying a holistic educational model that emphasised discipline, moral development, and intellectual inquiry. This legacy safeguarded Buddhist philosophy and established early models of lifelong, value-based education still relevant to modern pedagogy.

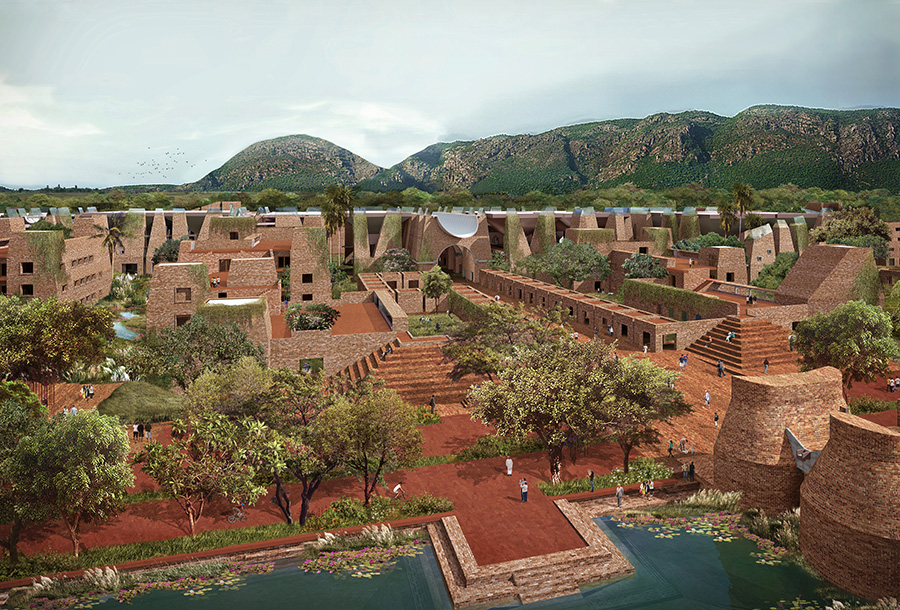

Nalanda represents the most sophisticated expression of this system. While earlier monasteries focused largely on spiritual development, Nalanda Mahavihara (5th–12th century CE) evolved into a vast, organised university with residential facilities and a structured curriculum. It integrated Buddhist philosophy with secular knowledge — teaching grammar, medicine, astronomy, mathematics, and the arts. Its multidisciplinary and inclusive approach encouraged debates, lectures, and commentaries, attracting students from China, Korea, Tibet, and Southeast Asia. More than a spiritual centre, Nalanda embodied the union of faith and reason, viewing education as a pursuit of universal enlightenment rather than sectarian learning.

In this spirit, the National Institute of Open Schooling (NIOS), in partnership with the Indian Himalayan Council of Nalanda Buddhist Tradition (IHCNBT), has launched a pioneering initiative to modernise and formally recognise monastic education across India. Traditionally conducted in Bhoti, this education preserves a rich repository of Buddhist knowledge and Indian literary heritage. The works of scholars like Nagarjuna, Vasubandhu, and Dharmakirti — alongside Sanskrit classics such as Meghaduta, Kavyadarsa, Amarkosha, and Ramayana — testify to its intellectual depth.

Covering Elementary, Secondary, and Senior Secondary levels, the programme bridges traditional wisdom with modern educational frameworks. Rajeev Kumar Singh, Director (Academics) at NIOS, calls it “a bridge between ancient wisdom and modern opportunity,” stressing that the goal is not to secularise Buddhism but to empower learners and ensure their knowledge receives equal respect while engaging meaningfully in modern society.

The IHCNBT, representing Buddhist communities across Ladakh, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh, Jammu & Kashmir, and North Bengal, plays a crucial role in institutionalising this effort. For Maling Gombu, its General Secretary, the initiative is both educational and patriotic — strengthening the Indian identity of monastic institutions and ensuring monasteries remain vibrant centres of learning rooted in Indian civilisation.

Today, about 132 monasteries across the Himalayas have been accredited by NIOS, enrolling nearly 10,000 learners. This historic integration of monastic education into the national framework is not merely an administrative reform — it is a cultural renaissance. The Bodh Darshan initiative dignifies centuries-old Himalayan learning, reaffirming India’s position as the spiritual and intellectual cradle of Buddhist thought.

The writer is a Senior Journalist who writes on socio-economic affairs; views are personal