The Jammu and Kashmir administration abruptly banned 25 books by authors, branding them “dangerous” under the new penal code. The attempt to silence books in the Valley feels less like a show of strength and more like an admission of fear

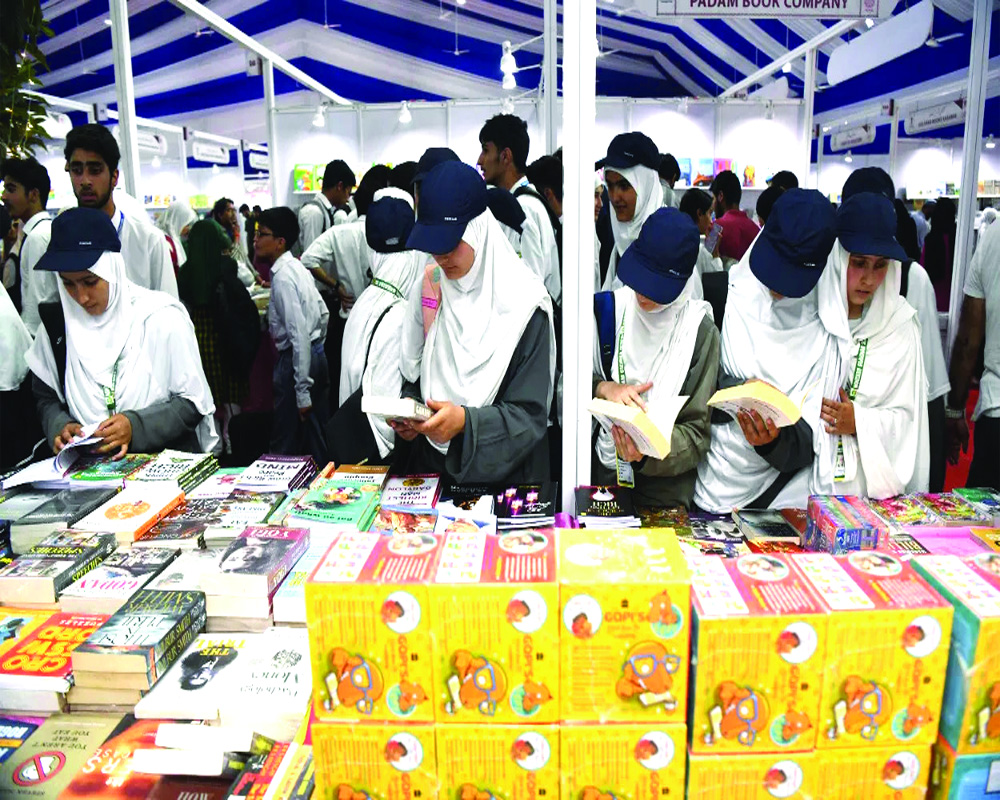

In an age when the world’s knowledge is a click away, banning books is like trying to dam a river with your bare hands — futile, messy, and bound to fail. And yet, on August 5, as the Chinar Book Festival in Srinagar — backed by the Union Culture Ministry — was meant to celebrate the written word, the Jammu and Kashmir administration under Lieutenant-Governor Manoj Sinha decided to pull 25 titles from shelves. These works, by noted authors like AG Noorani, Sumantra Bose, Arundhati Roy, and Victoria Schofield, were declared dangerous under Section 98 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita 2023, accused of “promoting false narratives” and “secessionism.”

The order warned of prison terms ranging from three years to life for possessing or distributing the books. Among the banned were Noorani’s The Kashmir Dispute 1947–2012 and Roy’s Azadi, with the Home Department claiming they “distort history, glorify terrorists, vilify security forces, and foster grievance, victimhood, and terrorist heroism.” Police fanned out to Srinagar’s bookstores, though so far there are no confirmed reports of seizures. What is striking is that most of these titles have been in circulation for years, published by respected houses like Penguin and Routledge. Their presence was neither new nor secret. Which makes one wonder: Why now? The timing is suspicious. August 5 marked the sixth anniversary of the abrogation of Article 370. Since 2019, Jammu and Kashmir has been governed as a Union Territory, with the L-G’s powers enhanced under the J&K Reorganisation Act 2019. Amendments to the Transaction of Business Rules in July 2024 granted Manoj Sinha sweeping authority over police, public order, the Anti-Corruption Bureau, and prosecution sanctions — powers that supersede those of Chief Minister. Omar Abdullah, who has opposed the ban, points out that he has never banned a book and never will. However, in a set-up where the real power resides with the Raj Bhawan, his opinion is more symbolic than decisive.

The official reasoning — “systemic dissemination” of secessionist literature — was presented without transparency or judicial review. It fits a long tradition of governments using censorship as a blunt instrument, often with counterproductive results.

History, in fact, reads like a graveyard of failed book bans. Renaissance Italy saw the moral fury of Girolamo Savonarola, who in 1497–98 led the “bonfires of the vanities” in Florence, burning “immoral” books and artworks. A year later, he was excommunicated, executed, and his ideals forgotten — while the very literature he sought to destroy flourished across Europe.

In 1933, Nazi Germany staged public book burnings, targeting works by Albert Einstein, Franz Kafka, Sigmund Freud, and other intellectuals. The Third Reich is now remembered as a cautionary tale, while Kafka’s Metamorphosis is studied in classrooms worldwide. India too has had its share of literary bans — Rama Retold (1954) for allegedly hurting religious sentiments, The Da Vinci Code (2006) for similar reasons, and bans on Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Lolita, Ulysses, and even The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. None of these ever truly disappeared; they are easily available online. Attempts at suppression only stoked curiosity and widened readership.

As the saying goes, you can silence a writer, but you cannot bury a book. In the modern context, the futility of such acts is even starker. Today’s world operates on an “information superhighway,” where banning a printed copy in one territory means nothing when e-books, PDFs, and scanned versions circulate freely across borders.

You can ban the ink, but you can’t ban the idea. The Kashmir ban, ironically, seems even more hollow because it applies only within the territory. Anyone outside Jammu and Kashmir — or with basic internet literacy — can access these books in minutes. The result? Locals who might never have heard of them now know their titles, authors, and “dangerous” themes. Far from suppressing the material, the ban is an unpaid advertising campaign.

There is also a special irony in banning books in a region that has a proud reading tradition. Sheikh Abdullah, long before he became the “Lion of Kashmir,” served as secretary of the Fateh Kadal Reading Room Party — later the nucleus of the National Conference. The idea that Kashmiri society is somehow unable to handle differing viewpoints insults not just readers’ intelligence but also the history of political literacy in the Valley.

Censorship of this kind has a peculiar side effect: It elevates otherwise obscure works into symbols of resistance. The Comstock laws in the United States, for example, attempted to regulate morality by banning “obscene” literature in the late 19th century — a movement so extreme it gave us the term “Comstockery.” The result? The banned works became must-reads for anyone wishing to challenge the establishment.

The current ban is more than a matter of free expression; it’s a test of whether India’s democracy can tolerate dissenting narratives, especially in sensitive regions. The state can — and should — challenge ideas it disagrees with through debate, scholarship, and counter-publications. But to wield Section 98 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita like a club against inconvenient books is to abandon persuasion for coercion. And coercion rarely changes minds; it only pushes them underground.

If the goal is to keep the peace in Kashmir, history suggests a different approach. Reading rooms, literary festivals, and open libraries have a better track record of diffusing radicalism than bans do. They create spaces for dialogue, allowing communities to confront ideas in the open rather than letting them fester in secrecy. When people are trusted with the responsibility to read and decide for themselves, the social fabric is strengthened, not weakened. The state’s heavy-handedness is also strategically flawed. Since the revocation of Article 370, the Government has repeatedly claimed that normalcy and progress are returning to J&K.

Literary festivals funded by the Centre were meant to showcase this openness. But the contradiction between celebrating literature on one hand and banning it on the other is glaring. It risks undoing the credibility such festivals are meant to build.

As every failed censor in history could testify — from Caligula to Savonarola to Goebbels — the surest way to make people read something is to tell them they can’t.

The writer is Professor at the Pondicherry Central University