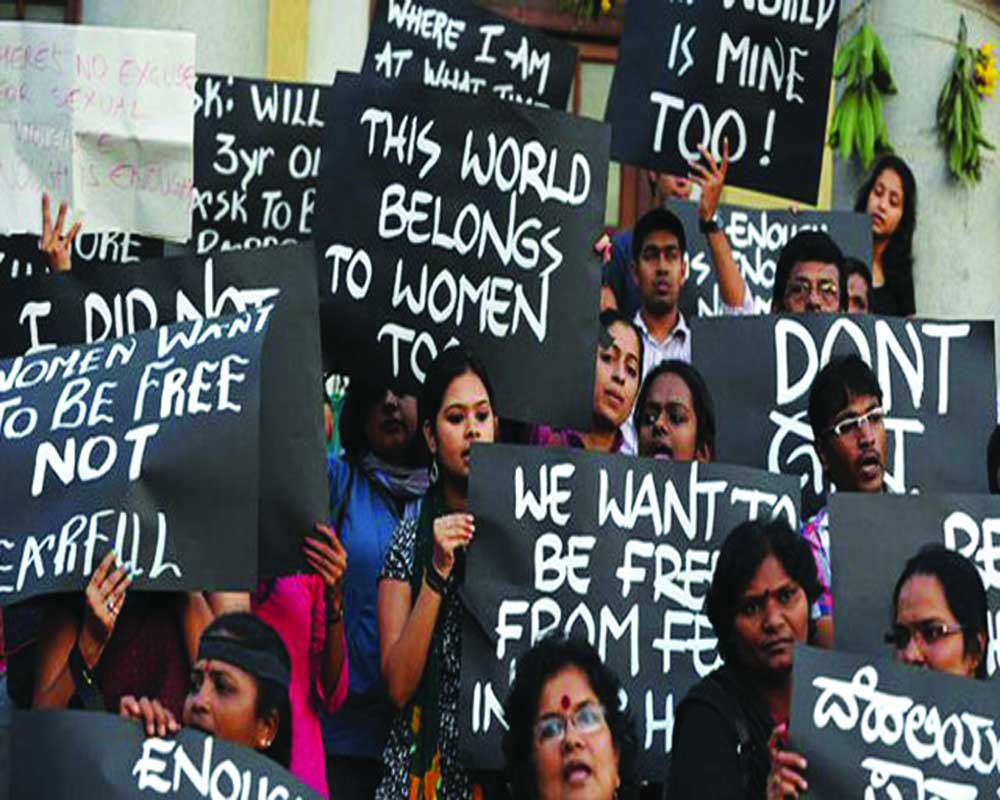

Without policy and legislative changes along with the refusal to alter conventional mindsets, India’s female population is unlikely to emerge from the morass of poor economic performance

As another year draws to a close, it is pertinent to ruminate Janus-like, once again, over past and future gender parity trends both in India and abroad. And the picture is not a pleasant one. In fact, the year is ending on a grim note for women all over the world, with the Global Gender Gap Report 2020 predicting that as things stand currently, overall, gender parity will not be attained for another 99.5 years. The report, which is being prepared by the World Economic Forum (WEF) since the last 14 years, examines gender parity in 153 nations on the basis of four dimensions: Economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health and survival and political empowerment.

Despite its gloomy forecast, this year’s report offers a mixed bag. While flagging greater political participation of women across countries, it asserts that gender parity has, in fact, been achieved in 40 of the 153 countries it surveyed. And the best performers, as usual, are the Scandinavian countries, with Iceland, Finland, Norway and Sweden leading the pack. Nicaragua, New Zealand, Ireland, Spain, Rwanda and Germany followed close behind to line up the top 10. As many as 101 countries succeeded in improving their scores over the 2019 rankings, even as nations like Albania, Ethiopia, Mali and Mexico rose above their economic challenges to grant consistent greater economic empowerment to their women.

But where does India figure in this count? In the bottom 50, coming in at rank 108 out of 153. This poor showing by an ostensibly rapidly growing economy is largely the result of a gender pay gap emerging from Indian women’s decision to stay out of the workforce or drop out of it due to various factors. Pointing out that India ranked lower on all the four segments being assessed, the WEF highlighted the need for India to “make improvements across the board — from women’s participation to getting more women into senior and professional roles.†The report goes on to say that the economic gender gap runs particularly deep in our country and has gotten significantly wider since 2006, with the country also being the only one among the 153 countries studied where the economic gender gap is larger than the political gender gap.

This curious decline in women’s economic participation despite a rise in their education levels has also been documented by the India Human Development Survey (IHDS), a nationally representative multi-topic panel survey of 41,554 households, conducted in two waves in 2004-05 and 2011-12 by the National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER) in collaboration with the University of Maryland. The IHDS not only covered a wide range of topics concerning health, education, employment, economic status, marriage and fertility but also canvassed an exclusive module administered to 33,510 ever-married women aged 15-49 years during the survey. According to IHDS data, many nations have experienced a U-shaped relationship between economic development, growth and women’s workforce participation. However, in India, unlike other South Asian countries, women have failed to rise above the bottom of the U-curve for several decades, irrespective of consistent economic growth, perhaps because the country’s formal economy has grown without offering any specific or substantial opportunities to women through feminisation of the labour force.

According to IHDS, women’s Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) fell alarmingly from 31.12 per cent in 2005 to 24.77 per cent in 2012. The IHDS findings have also been endorsed by the 68th Round of the National Sample Survey Organisation (2011-12), which, in turn, records a corresponding fall in the female LFPR, from 28.7per cent to 22.5 per cent since the previous NSSO survey. Concomitantly, the WEF report also lowered India’s gender ranking for economic opportunities from 139 in 2017 to 142 in 2018.

Another observation peculiar to India is the paradox of a decreasing Child Sex Ratio (CSR) or the ratio of girls to boys, which in 2016 was reportedly at the lowest level since 1951, notwithstanding progressively higher educational attainment among girls. Thus, even though more parents across States and communities have started sending their daughters to school and college, they still express a preference for sons for a variety of reasons, ranging from the prevalence of dowry, the burden of ensuring safety of girls and the support provided by sons in old age. As Carol Vlassof, Professor at the University of Ottawa and long-time researcher on gender issues in India, avers, “The bias against daughters can end only if women’s education is accompanied by social and economic empowerment.â€

Even worse is India’s gender-based performance in the domain of health and survival. The WEF report ranks the country third lowest for this parameter, just above Armenia and China, categorising it as the “least improved country†on this sub-index over the past decade. This result comes as no surprise, considering the fact that by and large, Indian women have little autonomy in decision-making even in matters of personal health.

Here, too, the IHDS report in 2005, which had surveyed over 74 per cent of the women, stated that they needed permission just to visit a health centre, let alone exercise control over their bodies and health-related issues. And this figure had gone up to 80 per cent when IHDS revisited its sample households in 2012.

Interestingly, among the women reporting the lack of agency in health matters, 80 per cent affirmed that they had to seek permission from their husbands, 79.89 per cent from a senior family member and even more significantly, 79.94 per cent revealed that they had to consult a senior female family member for such permission. The implication inherent in this finding — that women in dominant family roles tend to exercise stringent control over their less assertive female counterparts in the family — also has serious implications for female sorority and mutual support.

It is obvious that without policy and legislative changes and in view of persistent refusal to alter conventional mindsets that perpetually relegate women to household and care duties, India’s female population is unlikely to emerge from the morass of poor economic performance, coupled with low health outcomes and unequal access to opportunities.

Coming back to the 2020 Gender Gap Report, India would do well to heed the advice of the WEF Founder and Executive Chairman, Klaus Schwab that “only countries that are able to harness all their available talent, (both male and female), will succeed in the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Proactive measures that support gender parity and social inclusion and address historical imbalances are, therefore, essential for the health of the global economy as well as for the good of society as a whole.†Is India listening? Or does it want to retain its dismal position on the Gender Index next year, too?

(The writer is Consultant Editor at the National Council of Applied Economic Research. Views expressed are personal)