Spatial and structural characteristics of urban India indicate that cities, especially slums and the suburbs, are likely to remain hotspots for diseases like COVID-19 in the coming months

Symmetric to global trends, urbanisation in India has spread rapidly. This has led to the reordering of the urban periphery through complex processes of displacement of the central population to the margins and the creation of new functional nodes away from the traditional core. Adaptation to such realities came to a grinding halt when the pandemic hit the country. As has been evident, people of urban India — especially those living in slums and peri-urban areas — are more vulnerable to the rapid spread of COVID-19. This has brought to the fore the importance of the ways in which city governments are working to combat the spread of the virus. There is no denying that the interrelated dimensions of mobility and demographic change, infrastructure and governance influence the preparedness of urban India in outbreak management, right from disease prevention to mitigation and possible responses.

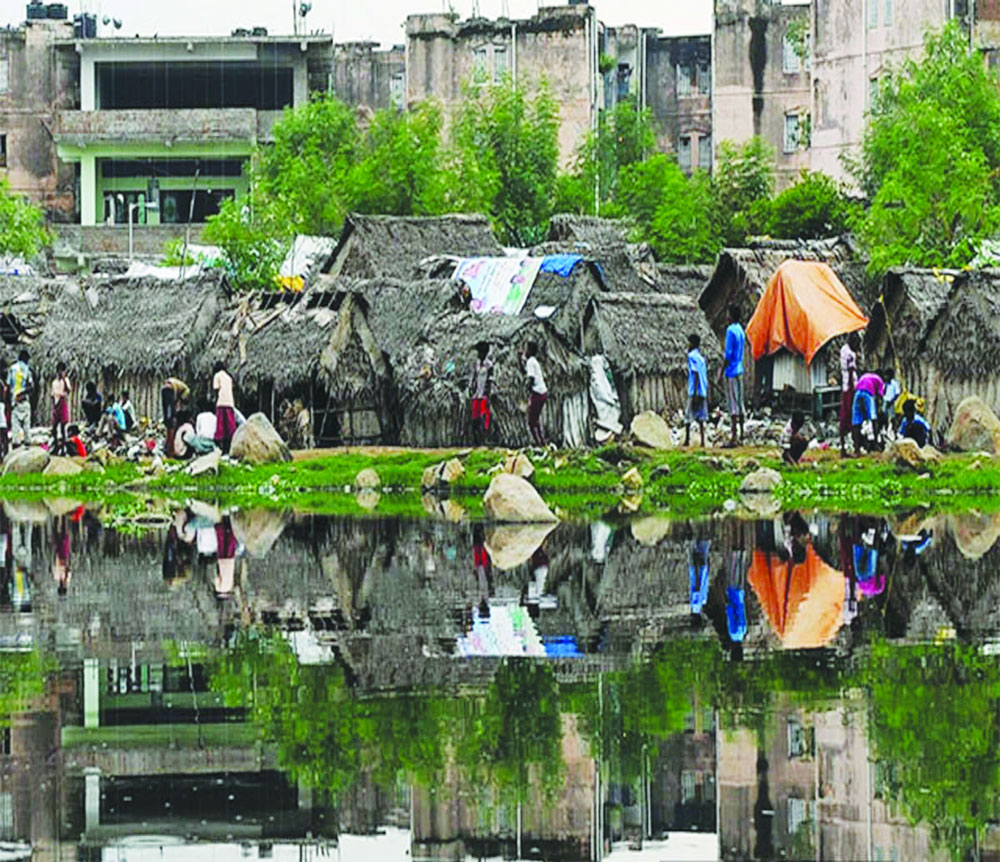

The dynamics of demography in the cities and COVID-19: High population densities in cities are major factors influencing the spread of disease. According to the Census 2011, India experienced a 37.14 per cent decadal growth in the number of slum households with 104 million people living in ghettoes in 2013, as per the data of Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA). Almost two-thirds of statutory towns in India have slums.

An overwhelming majority of the families living in the densely-populated areas of slums and peri-urban areas are migrant workers who are engaged in urban informal activities characterised by low wages, severe competition, tenuous job security with the need to travel daily to the city core to earn their livelihoods. Lack of work opportunities during the lockdown forced many of them to return to their villages. Such mobility patterns, owing to myriad social and political economic factors, bear the risk of spread of contagious diseases to the peripheries.

This points to the fact that infrastructure development for the benefit of this section of the urban population has not been adequate. A vast majority of the urban population, living in slums and peri-urban areas, lacks access to basic urban services, including water, electricity, sanitation, solid waste management and housing facilities. As per the estimates of the Technical Group on Urban Housing Shortages (2012-17) housing shortages are projected to increase to 34 million by 2022. According to the 2012 National Sample Survey (NSS), slums are incredibly packed spaces where three-fourths of India’s slum tenements are cramped within two hectares.

In such a situation, an outbreak of Coronavirus in places with unsafe and precarious living conditions, where even the basic preventive measures like social distancing and frequent hand-washing are impossible to achieve, could easily turn into a grave public health emergency. Indeed, the outbreak of contagious diseases is less of a “natural” disaster but emerges alongside social and spatial inequalities in housing and access to basic services.

Governance deficits: The deplorable state of urban services is typically attributed to poor financial health and lack of planning, which in turn are linked to weak institutional capacities and the absence of effective governance structures in Indian cities. The 74th Constitutional Amendment Act (1993) promised to improve the delivery of basic services by devolving resources and decision-making powers to local governments. Political empowerment is weakened by infrequent elections of Urban Local Bodies (UBL) and most States rest the executive authority of city governments on the State-appointed Commissioner, with the Mayor and city Councillors having very little authority over management, let alone on emergencies like COVID at the city level.

Although, city governments are expected to have complete authority to carry out functions, including water supply, sanitation, solid waste management, public health and slum improvement, yet the actual devolution of responsibility to the municipalities, even after 25 years of decentralisation, can at best be described as partial.

State Governments control key healthcare infrastructure such as hospitals, clinics and primary healthcare centres and even these institutions lack human resources, including medical officers and skilled staff. Overlapping institutional roles and responsibilities raise questions as to who should deliver urban basic services and the problems become far severe in case of managing and preventing potential outbreaks. This is very evident in the recent war of words between the Delhi Government and municipal bodies over inadequate beds in hospitals for the treatment of COVID-19 patients.

Capacity constraints: Infirm financial health of the ULBs has a regressive impact on their capacity to provide basic services. Assignment of finances is completely left to the discretion of the State Governments and ULBs can levy and collect only those taxes that are specified by the States. Municipal finances are in a grossly unsatisfactory state as they collect far less revenue than what is necessary to cover even the cost of providing urban basic services, let alone tackling any health emergencies. Lack of adequate skilled staff at the ULB level is another major drawback as there is far less emphasis on the institutional capacity of the local government. Appropriate institutional capacity enables ULBs to make policy decisions and implement them, in the manner they want, to produce the outcomes they desire.

The way forward: In essence, spatial and structural characteristics of urban India indicate that cities, especially slums and the suburbs, are likely to remain hotspots for diseases like COVID-19 in the coming months. An ability to monitor rural, urban and inter-urban migration will be crucial to mitigate the spread of this disease.Therefore, it would be useful to plan and implement a slew of short-term measures, including aggressive and affordable testing, tracing and quarantining of infected people, provision of door-to-door drinking water and mobile toilet facilities in densely-populated slum and peri-urban areas.

This pandemic provides an opportunity for genuinely empowering ULBs that should not go to waste. Cities with well-functioning governance and health infrastructure are better placed to manage pandemics and excess mortality than those that do not. In other words, the governance conundrum along with poor planning and weak healthcare systems can undermine the efforts to combat the pandemic and build upon the confusion, fear and panic.

Interestingly, in November 2019, the Global Parliament of Mayors met in Durban and the members committed to develop regional and local networks to advance the dissemination of trusted public health information. They also pledged to promote information sharing and communication measures in and between cities to prevent and reduce the international spread of infectious diseases.

In the medium and long-term, it is pertinent to identify the lacunae in city planning and the underlying socio-economic determinants of public health and resilient cities. This would help to streamline resource flows to vulnerable areas more effectively. It is equally important to create a city-level pandemic preparedness index, using details of a ward/locality/neighbourhood-wise vulnerable population and hospital- wise beds and ICU capacities. It will serve as an evaluation tool (similar to the Rapid Urban Health Security Assessment Tool developed by Georgetown University) to assess city-level public health preparedness and response capacities.

It is important to support the city governments to prioritise, strengthen and deploy strategies that promote urban well-being and health security. This pandemic provides a rare opportunity to work in tandem with the ULBs and genuinely empower them to discharge their functions.

Building municipal capacity to prepare action plans in advance for better preparedness on the ground, providing emergency response training and improving coordination with other key departments, like the National Disaster Response Force, should feature in any national urban policy framework and has to be necessarily embedded in the cities of a ‘New India.’

(Chattopadhyay is an Associate Professor of Economics at Visva Bharati University, Shanti Niketan and a Visiting Senior Fellow at IMPRI and Mehta is CEO and Editorial Director, IMPRI)