Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan was a rare example of community transition, who showed how easy it was to shed the cult of violence and walk the path of peace

India completed the year-long celebrations of the 150th birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi on October 2. One had the privilege of participating in several learned deliberations on the relevance of Gandhian ideas in the present context. In most of these, it was rather a unanimous conclusion that Gandhi’s principles, values and his life could give a healing touch to suffering humanity in a world characterised by wars, violence, distrust, hatred, fundamentalism, terrorism, arms race, hunger, poverty, ill-health and much more. Peace, non-violence and religious harmony remain elusive commodities. And Gandhi successfully demonstrated a non-violent path to human dignity, harmony and liberty. He could influence leading personalities within and beyond India, who plunged headlong into creating a peaceful world by following his values and successfully achieving attitudinal transformation within their communities and nation.

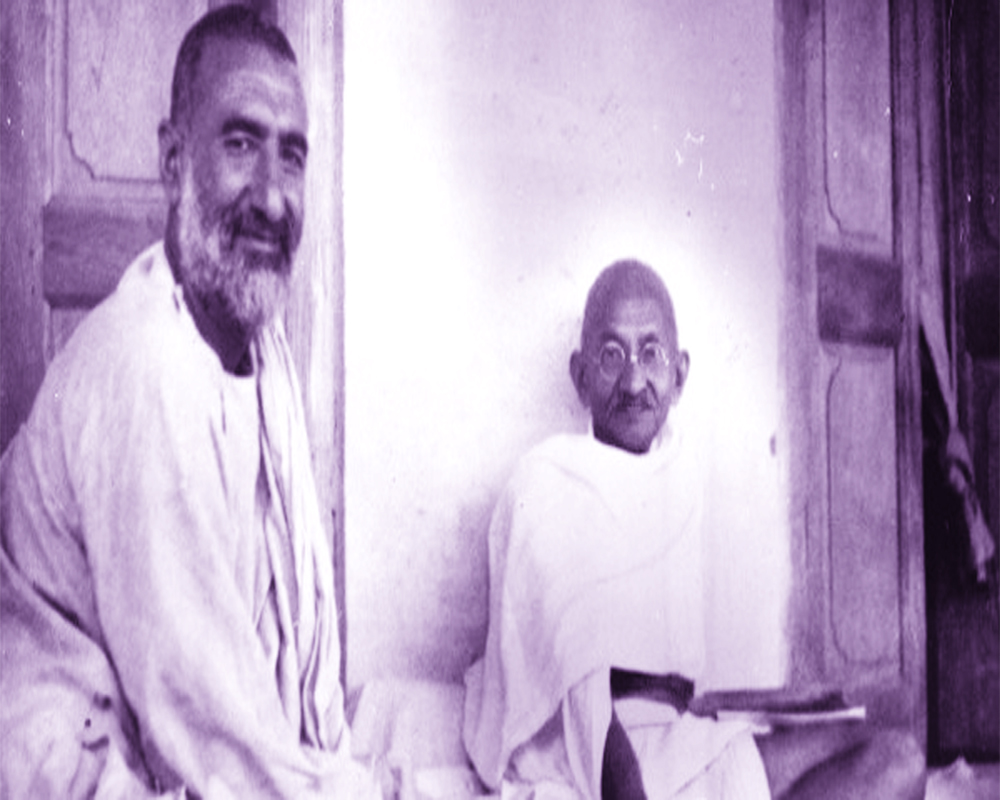

The life of Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, also known as Bacha Khan and Frontier Gandhi, presents one of the most scintillating examples of achieving a rare community transition from violence as a cult to the path of peace and love as the value of total commitment. His name may appear just as unfamiliar to most young Indians as his role as a stalwart in the Indian freedom struggle, and after Independence, as a fighter for his people in Pakistan, that he waged till his last breath on January 20, 1988. He finds little resonance even in India for various reasons.

In July 1942, Jawaharlal Nehru issued a statement on the happenings in the Frontier Province — now in Pakistan — clearly indicating how scarce the news from there was, and that too, was “often tainted and contained many wrong allegations.†Nehru had personally experienced difficulty, during his own visits to the Frontier Province, in sending out proper news through normal agencies or otherwise. He further observed that restrictions on such news being sent out were stricter in the Frontier Province than elsewhere in India. He then revealed a painful truth: “The result is that the people in the rest of India know little of what is happening in this highly important part of the country.†In this very statement, Nehru wrote about Frontier Gandhi. He said: “Few people know about the work that Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan has been carrying on during the last six months. He does not believe in ostentation but he has gone to villages seeing his people, organising them and encouraging them in every way. Thus, he has covered the entire province.â€

Apart from numerous impediments from various quarters, Khan also had to face false propaganda of vested interests. Born in 1890, he was greatly touched by the devastating misery of his own people which, he concluded, was due to the lack of education and consequent ignorance. He started schools and the British did not like it. He was 19 when he was first imprisoned and then it was a life in and out of jails of the Britishers, and then the Government of Pakistan. His historic movement, Khudai Khidmatgar, was launched to overcome poverty and banish the British from India. He was, till the end of the freedom struggle, for a united India.

Khan was inspired by Gandhi’s message of non-violence and he knew how difficult it would be to convince his “freedom-loving†Pathans to execute the idea. He had the courage and conviction to accept the challenge and he achieved this miracle. The type of attitudinal transformation achieved by this charismatic personality could only be termed unparalleled. He gave a new interpretation of force, courage and valour to his people and the community. This, he could do through his creative leadership, deep and thoughtful interpretation of Islam as a religion of peace. He was a man with a universal message of brotherhood and camaraderie. He knew how vibrant the cultural heritage of his people and the region was, and how this cradle of learning and culture sank “into a state where there was no room left for such good work such as education and learning.â€

While India was celebrating the birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi, an erudite scholar of post-Independence history, RNP Singh, was searching literature and sources in libraries and institutions to put up an authentic account of the great Gandhian, Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan. And how India ignored his contributions which had the potential to bring forth peace not only to the erstwhile North-West Frontier Province (NWFP), Afghanistan and Baluchistan but to the entire Middle East region, and even beyond.

Singh has established, based on his study, how great was the measure of wrong done to this frontline freedom fighter and an exceptional devotee of Gandhi. In his seminal work, Durand line: Did India Fail Frontier Gandhi, Singh very succinctly summarises: “He was among the very few leaders of undivided India who, by dint of their sincere effort and selfless service to their people, rose to eminence and earned a niche for themselves in the top political hierarchy of the country. Yet in spite of having earned a place among the galaxy of eminent leaders, Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan never advanced his claims to recognition in the Indian context.†One could say without hesitation that India failed Bacha Khan, his Pakhtoon people and the NWFP. There is no other way out of this but to follow the path shown by Gandhi and Bacha Khan.

During the freedom struggle, Gandhi tried his best to persuade the Muslim League and Mohammad Ali Jinnah to give up the two-nation theory. He failed in his persuasion and India suffered the ghastly tragedy of the Partition. And we still need persistent efforts to strengthen our efforts to cement the age-old mutual harmony between the two major communities.

Inspired by the increasing influence of Gandhi, whose persona and ideas had begun to influence the remote North-Western part of the empire and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, young Bacha Khan opened schools for both boys and girls. He organised young people under the banner of servants of God — Khudai Khidmatgar — who, contrary to the prevalent tradition, decided to follow the Gandhian path to achieve freedom for India and its people. To these highly motivated and committed people, his message was, “The fundamental principles of all religions are the same though the details differ because each faith takes the colour and flavour of the soil from which it springs… I cannot contemplate a time when there will be one religion for the whole world.†And this came from a devout Muslim who never missed a namaaz and who also had “the spirit of brotherhood†innate in himself more than many so-called orthodox Muslims.

Religious fundamentalists and protagonists of the two-nation theory, expectedly, disliked him and his approach and inflicted numerous cruelties on him and his followers once they came to power. The persona of this Frontier Gandhi, sufferings that he endured even after Independence, must be revealed to young Indians, who are working for religious amity as the core value that could lead India to its destination of honour and acceptability in a strife-torn world.

What happened to Bacha Khan or what was done to him is summed up by Mohammed Arif Khan in the foreword to the treatise by Singh: “As an Indian, I feel that what we did to Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan and the Pashtuns in 1957 was very unfair. The Pashtuns had voted in 1946 for a united India but the decision of the Indian leadership reduced them to being subservient to the breakers of Indian unity. The result was that Khan and his followers were treated as traitors and he spent more time in jails of Pakistan after 1947 than in British jails before 1947.†All this happened in spite of the fact that the top Indian leadership of the freedom struggle was fully aware of the significance of Bacha Khan’s contribution and his unflinching commitment to a united India. Sadly enough, India was divided. Even Gandhi, who had declared that Partition could take place only over his dead body, accepted it. All that the great Bacha Khan could say to the Indian leadership that had accepted the Partition of this great country was: “You have thrown us to wolves.†He and his people were left at the mercy of those who never liked him for his liberal stance on Indian culture, history and his progressive ideas about religious harmony and social cohesion.

(The writer works in education and social cohesion)