Over the centuries, rich tradition of using floral designs in textiles has evolved in various forms all over the country, writes Alka Pande, as she explores perceptions and interpretation of flowers in her book, Flower Shower: The Culture of Flowers in India. An edited excerpt:

In bright attire of flowers forged new, Heavenly of colour, white, red, brown and blue.

—William Dunbar

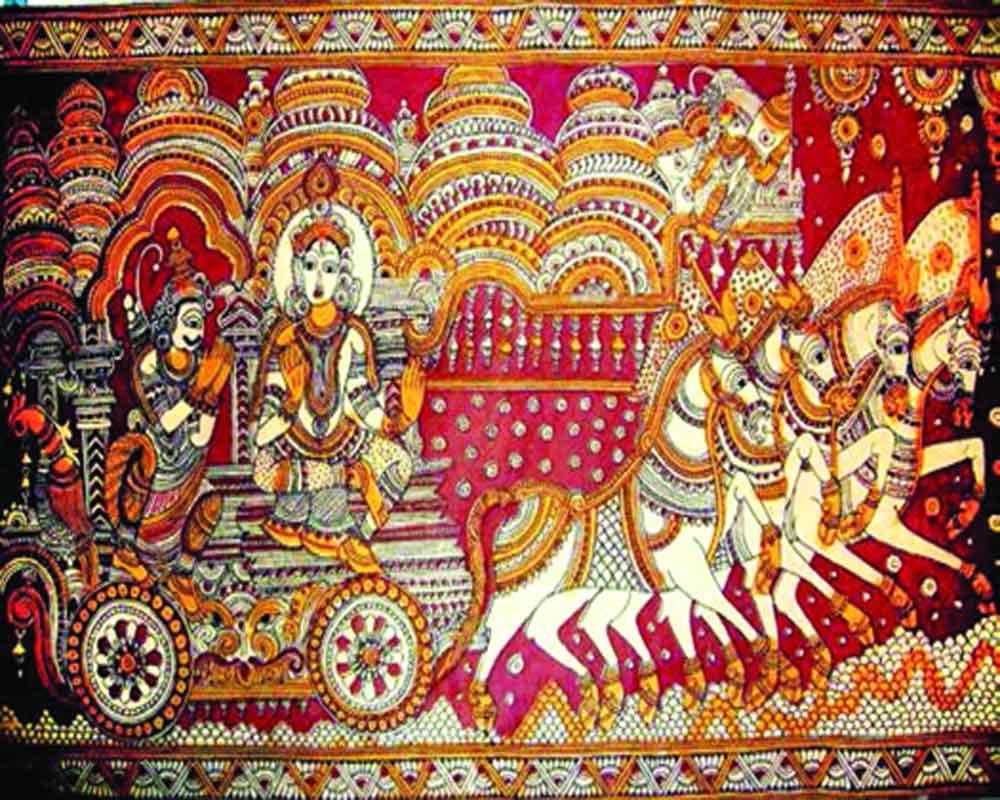

Flowers have been an inspiration for textile patterns since ancient times in India. The floral motifs on the costume of the red male torso from the Indus Valley civilisation show a visible refined version of the jasmine. Numerous Ajanta murals depict people wearing delicate garments with lotus patterns. Over the centuries, a rich tradition of using floral designs in textiles has evolved in various forms all over the country. Among different styles are the kalamkari and ikat traditions of Andhra Pradesh, the Paithani weaves of the Deccan, the embroidered shawls of Kashmir, the patolas of Gujarat, phulkari of Punjab, the Kantha and Jamdani of Bengal and Chamba rumals (handkerchiefs) of present-day Himachal Pradesh, as well as pictorial shawls that have worked images of birds, animals, flowers, plants, landscapes and other natural wonders that can be found across the length and breadth of the subcontinent. Every piece varies in terms of the hues employed, the patterns, the embroidery and its intricacy. The wealth of designs that form the motifs can vary from the symmetrical to the abstract to depictions of the rich flora and fauna of the subcontinent.

Each of the 29 states has its own tradition of weaving, embroidery or block printing and each state has distinctive floral motifs which defines its unique sensibility.

THE ESSENTIAL MOTIF

Images of flowers and flowering plants form a leitmotif that have run through the textiles of India, whether made by a village woman for her family, by a court artisan, or by a professional weaver for the export trade. Although some of the most common flower motifs (buta) and the paisley on Kashmir shawls can also be so stylised that they may appear to be simply abstract forms, their roots are firmly embedded in a love of gardens and flowering plants that dates back at least to the court cultures of the early years of the Safavid Dynasty in Iran (1501-1732) and the Mughal Dynasty in India (1526-1857). They take on many avatars such as embroidered shawls made by artisans for themselves to the buta in twill tapestry that were carefully crafted and then sent abroad to enter the realm of the European elite.

Nora Fisher notes that in Gujarat, village women, as well as professional embroiderers from the Mochi community would take the aid of drawings when they were creating their designs at the turn of the nineteenth century.

It is therefore interesting to note that the buta that border many shawls came about after various concepts and ideas about floral designs were synthesised from medieval Iranian images, pre-Islamic nature imagery and botanical drawings from France and the Netherlands. The final outcome was so beautiful that it dotted the cultural landscape of the Mughal world and was favoured by peasants and nobles alike.

Asawali and Amarvell, western India: The Satavahana Dynasty in 200 BCE made the city of Paithan its capital, alongside the holy Godavari river. The Paithani style is named for this city, renowned as it was for an over two-millennia-old textile tradition that hinged on carefully weaving multi-coloured threads together with gold and silver into a single, magnificent piece. It was but natural that the Satvahana rulers would then go on to give the Paithani style great impetus, being responsible for its spread across the Deccan. So favoured did it become that the style endured under the rule of other kings, the Mughals stamping their mark on it with the addition of floral patterns and the amarvell (flowering vine) motif. It even charmed the cold-hearted Mughal monarch, Aurangzeb, under whom it evolved.

Elegant additions such as asawali (flower pot with a plant) motif, the peacock, geometrical figures and flowering vines were made to the Paithani style as it continued to mature. For example, under the watchful eye of the nature-loving Emperor Jahangir, Paithani grew to acquire many additions in the form of designs that mimicked flowers and other natural wonders. With the rise of the Peshwas and the waning influence of the Mughals, the former became great patrons of the Paithani, the asawali or flowering vine being one of their prime contributions in terms of design.

From the land of the Chinar, northern India: Shawls woven in the Kashmir Valley are replete with floral motifs and naturalistic designs incorporating animals, birds and trees. Kashmiri embroidery is known as ‘kashida’ a vibrant and lovely reflection of the natural beauty of its homeland featuring creepers, leaves of the chinar, mangoes and floral motifs. The Kashmiri shawls popularised the ‘paisley’ design, which — over the years — became the defining motif of the Kashmiri pashminas. The four particularly popular shawls from Kashmir, the pashmina, the kanikar, the dorukha and the jamavar have floral motifs intrinsic to their design.

WEAVES — SILKS AND BROCADES

The Banarasi is one of the important brocades of India. The Banarasi ‘naksha,’ a Persian device which was similar to the jacquard loom enabled the weavers to weave the undulating floral patterns in intricate brocades and kinkhwabs (heavy silk fabric). From realistic roses, to stylised lilies and paisleys, the repertoire of the flowers was expansive, inclusive of the local flowers grown in the region.

FLORAL MAGNIFICENCE ON THE FLOORS

Carpets, rugs and namdahs, panja daris: There are numerous references to woven floor coverings in ancient and medieval Indian literature. Some Buddhist texts mention the presence of woollen carpets from as far back as 500 BCE. Pre-modern India saw the presence of woven bamboo mats and dhurries. For example they are mentioned in the Mrcchakatika of Sudraka. Mats are an age-old cottage industry, references to which are found in the Atharva Veda which mentions mats made of grass or kapisu and madur kathi mats made from madur kathi reeds. These were made for priests and Brahmans to sit on, as well as to cover the floors in wealthy households. Woven mats were also found in the Indus Valley Civilisation. All hand-woven, some of them had abstract floral patterns on them.

However, the most luxurious examples are found in the hand-knotted carpets which were introduced to India when the Mughal Emperor Babur made it his home. Babur sorely longed for the luxurious trappings of Persia and it was his grandson Akbar who laid the foundations for the carpet weaving industry at his palace in Agra in 1580. The Mughals not only followed the Persian technique of carpet weaving but were also deeply inspired by the traditional designs and motifs from Persia. The Persian carpets generally had a battle scene in the foreground with exquisite, fine worked borders of vines and flowers. In the Mughal courts, the Persian carpets were recreated with Indian forms and the patterns of these newly birthed Indian carpets varied from patterns featuring creepers and flowers originally with multiple shades of blues and greens on a red and peach base.

Another traditional floor covering of India is the dhurrie. Dhurries can be made of cotton wool, silk or jute and the material depends in the state on which they are made. In Punjab and Rajasthan the dhurries are known as Panja dhurries. Khairabad and Sitapur in Central India are some other centres for dhurrie making. These intricately woven floor coverings often feature geometric patterns which are inspired by the natural vegetation of flowers and vines.

From the states of Himachal Pradesh, Kashmir, Gujarat (Kutch) and parts of Rajasthan come some felted wool carpets known as namdahs. This is an Urdu word, brought to India by the Mongols and Mughals. Chain stitch embroidery is used to create beautiful floral motifs, particularly trees and flowers, translated by the artistic imagination of the artisan.

Excerpted with permission from Alka Pande’s Flower Shower: The Culture of Flowers in India, Niyogi Books, Rs 1,995