Syama Prasad Mukherjee was thoroughly grounded in Indian ethos which actuated his political choices. Throughout his political life, he prioritised ideals over positions

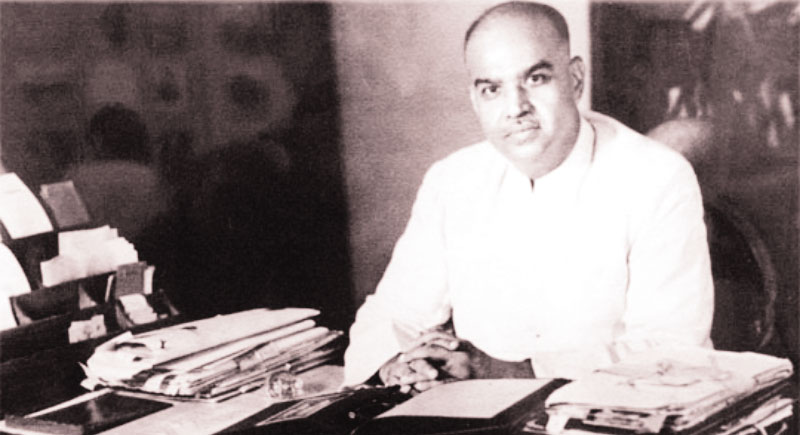

It is a truism that occasion produces the leader. One of its telling examples would be Dr Syama Prasad Mukherjee (1901-1953), independent India’s first Minister of Industry and Supply and founder of the Bharatiya Jana Sangh in 1951. His 118th birth anniversary is being observed today (July 6). A qualified barrister by training, his passion was education, academics and Indian culture. A Vice-Chancellor of the Calcutta University at a mere 33 years — the youngest ever in India — he would have preferred to spend a lifetime in the hallowed portal of goddess Saraswati. However, the perilous political situation in undivided Bengal in the late 1930s compelled him to pursue active politics. Over the ensuing 14 years, he came to occupy an important place in national politics. He had become a symbol of new national aspiration when he passed away prematurely at the age of 52.

The party he co-founded, viz, the Jana Sangh, on the eve of India’s first general elections, felt orphaned at his untimely death. It had anyway put up a modest showing in the election. But it was the purity of his vision that impelled the party to increase its tally and mass base at every successive election from 1957 to 1977. It was the largest constituent that formed the Janata Party Government (1977-1979) and later took shape in its new avatar, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

But it is not for the sake of partisan politics or even his individual political brilliance that we remember him today. His parliamentary career was as brief as six years between 1947 and 1953. But what sets him apart and makes him a stuff of remembrance is not his characteristic brilliance but the principles he lived and died for. He gave up his Cabinet rank in protest against Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s response towards the plight of the Hindu minority in East Bengal (erstwhile East Pakistan) in 1950. Three years later, he laid down his life to uphold the status of Jammu & Kashmir as inalienable and an integral part of India. Conscience always outweighed authority in Dr Mukherjee’s plan of action.

Education ran in the veins of Dr Mukherjee. His father, Sir Asutosh Mookerjee (1864-1924), five-term Vice Chancellor of the Calcutta University, had turned the institution into a constellation of talent. Sir Asutosh was deeply imbued with the Indian ethos and wanted his son to do post-graduation in Bengali literature. Dr Mukherjee, having graduated in English literature with flying colours, chose to switch over to Bengali for post-graduation. He promoted serious research in Indian history from an Indian standpoint, opened the university’s first museum of Indian history, culture and archaeology and invited foreign universities to send their students to study Indian civilisation, culture and Sanskrit.

Apart from promoting serious research in Indian history, he also initiated a course in Islamic culture and history. Breaking the convention, Shri Mukherjee invited Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore to deliver the convocation address in Bengali for the first time in 1937. He also strongly believed in inculcating patriotism and love for the motherland among the students as also promoting our culture and civilisation. In September, 1939, he came in contact with Veer Savarkar and joined the Hindu Mahasabha. Soon afterwards, Dr Mukherjee was appointed its working president, which necessitated him to travel all across the country. Even Mahatma Gandhi welcomed his decision.

The Hindu Mahasabha years gave Dr Mukherjee the opportunity to demonstrate his leadership qualities, oratorical skills and organisational abilities. His first meaningful contact with the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) happened during that time. “I see in this organisation the one silver lining in the cloudy sky of India”, said Dr Mukherjee while addressing the Swayam Sevaks in Lahore in 1940. His relationship with the RSS became his capital when he founded the Bharatiya Jana Sangh 11 years later.

Impressed by his nationalistic outlook, Mahatma Gandhi insisted that Dr Mukherjee be included in the first Union Cabinet headed by Pt Jawaharlal Nehru. In spite of his reservations to be part of a Congress-led Government, he joined the Cabinet following the advice of Veer Savarkar.

As India’s first Minister of Industries and Supply, he piloted the industrial policy and laid the foundation for industrial development in the country. He believed in encouraging the private sector while creating a strong public sector base in the country.

He never hankered after power and placed the interests of the country above everything else. He had quit the Nehru Cabinet in protest against the Liaquat–Nehru Pact, which sought to protect the rights of minorities in India and Pakistan following the attacks on Hindus in East Pakistan. Dr Mukherjee wanted exchange of population and property at governmental level as a solution.

The Bharatiya Jana Sangh was proof of Dr Mukherjee’s farsightedness. The sapling planted by him, with the benefit of time, has today grown into one of the world’s largest political parties. Dr Mukherjee, the unofficial leader of the Opposition, was in no mood to rest on his plumes. In a short span, he emerged as one of the tallest parliamentarians and his speeches used to be heard with rapt attention by one and all.

Soon, he found the issue of fuller integration of Jammu & Kashmir close to his heart. He advocated the concept of One Constitution, One Flag and One Prime Minister for the country, saying “Ek desh mein do vidhan, do pradhan, do nishan, nahi chalenge” (Two constitutions, two heads of states, two flags in one country is not acceptable to India).

He lent his support to the movement of Praja Parishad, founded by Pandit Prem Nath Dogra, for fuller integration of the state with India. He visited the state once in 1952 when he had spoken to Sheikh Abdullah and Pandit Dogra. When his extensive correspondence with Pandit Nehru and Sheik Abdullah on the subject failed to break the deadlock, he decided to visit Jammu again to lend support to the satyagraha there.

But this visit, started on May, 8, 1953, was about to prove the last ever journey in his life. He was arrested on May 10, 1953, by the state police for entering Jammu & Kashmir without permit. He was flown to Srinagar and confined to a small cottage near Nishat Bagh, where he spent the last 40 days of his life as a prisoner before he died in a hospital under mysterious circumstances.

Following his death, Dr Mukherjee’s mother, Jogamaya Devi, wrote to Pandit Nehru seeking an impartial probe, which, however, was not accepted. In her reply to the condolence message sent by Nehru, she wrote, “I am not writing to you to seek any consolation. But what I do demand of you is justice. My son died in detention — a detention without trial”, she stated. On his birth anniversary, the best tribute to Dr Mukherjee would be to inculcate the values of nationalism and patriotism among the younger generation and to strive for protecting our culture, traditions, civilisational ethos and the unity and integrity of the country.

(The writer is Vice President of India)