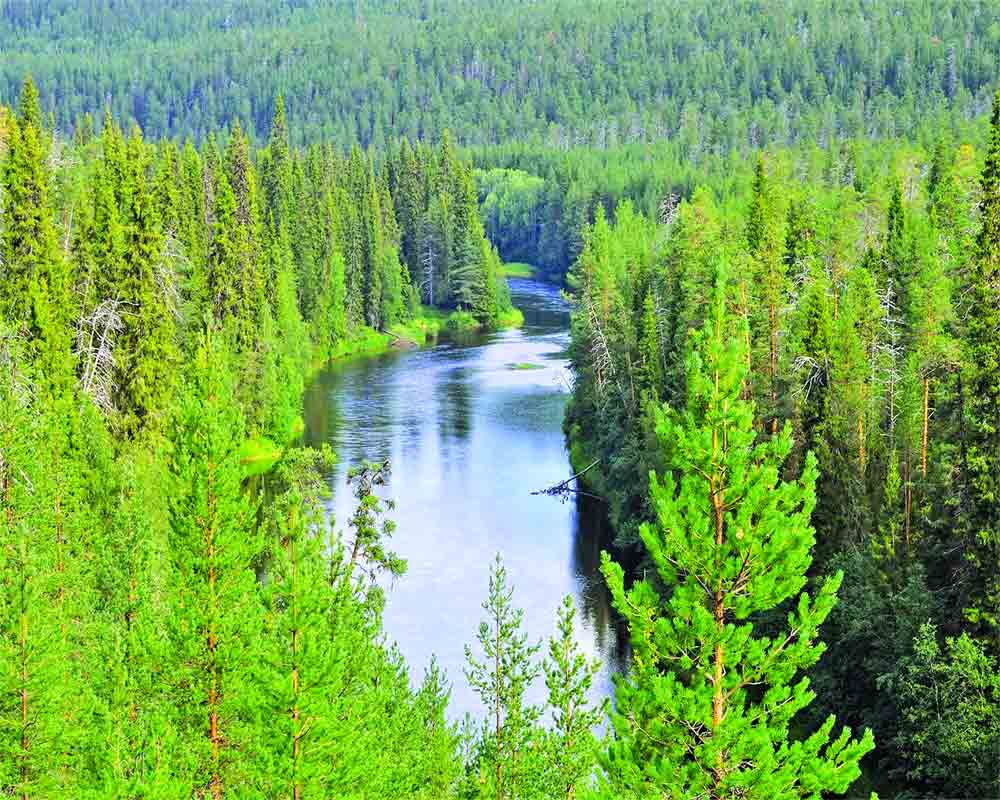

Since forests are the primary source of almost 75 per cent of freshwater in the world, there’s a need for concerted global efforts to conserve these

Approximately 75 per cent of the world’s accessible freshwater resources come from forested watersheds on which over half of the global population relies for their basic needs. Forests and trees play essential roles in the water cycle and are therefore vital for our water security. They not only influence how and where the rainfalls take place but also act as a natural water purifier. They regulate the quantity, quality, and timing of water.

Despite the important interlinkages between forests and water, the forest-water relationship is often overlooked in policy-making and planning. Only 25 per cent of forests are managed, with water as the main yield. Water-related ecosystem services are crucial for sustainable and responsible forest management – contributing to Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 12: sustainable consumption and production patterns – and maximizing water-related ecosystem services.

It is also fundamental for achieving many other SDGs, including providing clean water and sanitation, food security, combating climate change, etc. Over the past two centuries, forest cover and structures have been impacted globally by anthropogenic activities, like, fragmentation, over-exploitation, and land-use change. In consequence, these factors have influenced the hydrological processes in forested watersheds and altered the groundwater, base flows, and precipitation patterns at both local and regional levels.

Hence, balancing the competing demands for water and non-water natural resources from forests should be a major forest management challenge. Understanding how various environmental, physiological, and physical drivers interactively influence hydrological and biogeochemical processes in forest ecosystems is critical for sustainable water supply to forested watersheds.

According to a United Nations report, the world is likely to face a 40 per cent water deficit by 2030. Global water demand will increase by 55 per cent by 2050, largely due to climate change and galloping population growth. Therefore, forest management approaches focused on biomass production need to be transformed into a water-centered approach to prioritize water-related ecosystem services.

Comprehensive, integrated water and land management plans are urgently needed to tackle the problem of water quality and availability. We also require new management approaches, models, and best management practices to ensure healthy watersheds. For example, watershed restoration measures like slope stabilization, gully control, and landslide prevention can increase water-related ecosystem services.

Watershed programmes demand knowledge of the diverse local and regional contexts across India, where one-size-fits-all approaches are unlikely to succeed. The average rainfall in India is approximately 118 cm. Forest as a hydrological unit receives about 92 million hectares (Mha m) of precipitation, percolation into the soil, immediate evaporation, and surface water accounting for 49.5, 16.10, and 26.45 Mha m respectively.

About 23 per cent of the land is covered with forest vegetation, which transpires about 55 Mha, compared to 55 Mha m by irrigated and unirrigated crops that occupy 46.5 per cent of land area. Evaporation losses are lumped at 60 Mha m but work out to 13.8 Mha m for forested land.

The immediate evaporation is calculated at 70 Mha m and the forest area is estimated at 16.10 Mha m. Based on the available data, about 25 Mha m of water can be stored in the forest soil mantle on a sustained basis. Foresters seldom tried to understand the amount of water received from the forest and the quantity of water dispersed from it, for example -- Transportation of water from different forest stands or compartments; Interceptions from forest stands, forest types, management regime, etc; Permeability of forest soils; Inter and base flow from forested tracts and its impact on stream flow; Evaporation losses from forested areas as compared to their other land uses; Quality of water received, processed, and discharged.

If one was to restore water in a reservoir it would cost enormous money. Therefore, considerable efforts are needed to establish and maintain an extensive, intensive, and efficient network of forest meteorological stations for collecting data on snowfall, rainfall, hail, dew, wind, temperature, humidity, evaporation, radiations, etc. A better understanding of the interactions between forests and water (particularly in watersheds) is also essential for enhancing forest-water management strategies and action plans.

Forest management practices such as gap filling, restoration, and protection can increase water yields, regulate water flow, minimize surface runoff, and reduce drought effects. Forests intercept precipitation, moisture that evaporates from vegetation surfaces, transpire soil moisture, capture fog water, and maintain soil infiltration, thereby increasing the amount of water available from groundwater, surface watercourses, and water bodies. By improving soil infiltration and soil water holding capacity, they influence the quality and timing of water delivery.

Forests protect water bodies and watercourses by trapping sediments and pollutants from up-slope land uses. However, the extent to which forests perform these functions depends on local conditions, including soils, forest types and their density, structure, vegetation, climate, mining, etc.

The effects of such plantations remain a major research question for the scientific community. Thus, forest management decisions must be based on science and an understanding of forest-water relationships at different temporal and spatial scales as well as changing climate conditions. In some circumstances, land use change may involve the removal of ground litter along with vegetation cover, resulting in increased soil erosion, sedimentation, and deterioration of water quality.

Forest managers need to strike a balance between optimizing water yield and keeping an adequate canopy to minimize soil erosion, maintain albedo and enhance water quality. They also need to consider the impact of land-use change on hydrological processes at local, regional, and global levels and across seasonal, annual, and multi-decade time frames.

Much-needed research and monitoring on forest-water interactions, along with forest and tree management for water-related ecosystem services are required. Therefore, awareness raising and capacity building in the forest-water nexus and forest hydrology is necessary to ensure that we apply our knowledge to better manage forests and trees for their multiple benefits, including water quantity, quality, regulation, and the associated socio-economic benefits.

The importance of embedding this knowledge and research findings in policies is paramount. It is also necessary to develop institutional mechanisms to enhance synergies in forests and water issues and to implement and enforce national and regional action programs.

However, management of forest and water resources often falls under different jurisdictions, and due to the narrow focus of both sectors on their respective subjects, it has been challenging to reach a consensus and ultimately establish collaboration between the forest and water sectors.

(The author is Ex. Principal Chief Conservator of Forests, UP)