Ever since he has helmed the Fashion Design Council of India (FDCI), Sunil Sethi has revolutionised the business of fashion and changed the dynamics of the industry, which once sought Western approbation and which now takes pride in celebrating things Indian and selling big at home, says Rinku Ghosh

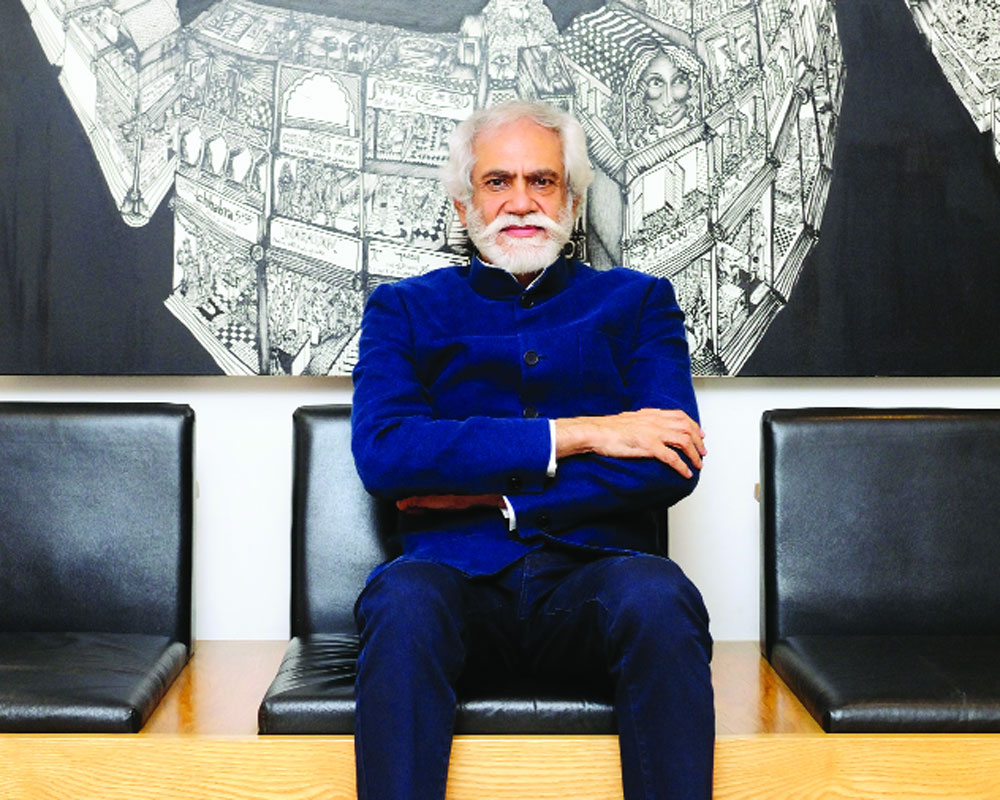

There’s hardly a fashion event where you can miss the earnest man, not one strand of his silver hair ever out of place, his moustache curled up, not with bravado but with contentment and the neat wrap of a beard never daring to trespass the trim. He’s ever energetic and involved in every show, hardselling the virtues of our craftsmanship, creativity and style. Ever since he has helmed the Fashion Design Council of India (FDCI), Sunil Sethi has revolutionised the business of fashion and changed the dynamics of the industry, which once sought Western approbation and which now takes pride in celebrating things Indian and selling big at home. He has single-handedly developed the pret market, encouraging young talent and street fashion, while hiving off couture as a grander, culture club space. In the process, he has birthed a movement of rescuing our heritage of textiles and weaves, breathing life into Government clusters and ensuring the weavers and artisans still have reams of continuity.

Relying on his past experience as exporter and merchandiser, he has encouraged a sustainable business model of fashion and effectively taken it to the online space. Every corporate now wants to endorse a fashion week. Sitting on the cusp of change and welcoming winds of change, Sethi talks about how brand India is now a sensible rather than an emotional investment. But yes, he is totally emotional about his Ambassador.

Many seasons into fashion weeks, the FDCI — despite being supported by the Government — has emerged with an independent, stable identity that has turned fashion into a serious business. How have you helmed the transition?

The approach from the very beginning has been to be self-reliant. We have never really waited for Government money, though we were getting support from the Ministries of Textile and Commerce. However, what is more important is that we have the Government support in terms of any project we undertake, in terms of collaborations. In the current fashion week for example, the Ministry of Textile with DC Handlooms curated a special show with us. Such initiatives have helped us develop and mainstream weaver clusters and revive our textile heritage. For almost two years now, we have tried to work with production hubs of handloom weavers, like those of Telangana ikat and the Banarasi brocade. They even got in Australian designers to work with the fabric and come up with products and lines that have contemporary sensibilities and address a global audience. Recently, each fashion designer was roped in for design interventions at weaving centres and clusters and the money was sufficient to take care of the expenses. Interesting tie-ups like these have helped us widen the interpretative arc of fashion.

The real evolution has been in the appreciation of fashion as a serious cultural and economic benchmark. Previously, it was associated more with glamour and lifestyle and neither a politician, nor a serious player was ever seen in the front row. Now ministers and politicians are opening these shows and walking alongside weavers and craftspeople on the ramp, lending fashion its rightful dignity as a fine art. Fashion today is going to the next level in terms of not only handlooms and handicrafts but also being adapted across multi-utility platforms as one of the drivers of the local economy. Corporates are engaging meaningfully, too.

In fact, a few years ago, the then Chief Minister of Gujarat, Anandiben Patel, was also happy to get on the ramp after a show on khadi and speak to the audience about the textile strength of Gujarat. Jyotiraditya Scindia walked the ramp along with weavers to focus on our Chanderi project. Our ‘Make in India’ man, Niti Aayog’s Amitabh Kant, has always been around to appreciate our shows. In Mumbai, we did a Banaras night with a chef and a leading hotel. Many of our leading designers presented their Banaras handloom collections. Union Textile Minister Smriti Irani had two very successful ‘I love handloom’ and ‘cotton school’ campaigns on social media, which nobody had ever thought of before. These are very big statements.

They may be in politics but by promoting textiles, the region, jobs and emphasising that this industry is the second largest employer in the country, they have changed the perception about fashion and made us feel invested in our own heritage. Fashion is no longer seen as an unattainable concept beyond the lakshman rekha. We have crossed the boundary and that is a very major step, bigger than getting funds from the Government.

How would you define the design revolution, this resurgence of ethnic consciousness and wearing our own identities as it were?

I can explain this by citing the example of the Incredible India campaign. We were very happy to travel abroad and boast about it, but as soon as the campaign had a global impact, we started looking within. I remember there was a sudden rush and curiosity among North Indians to visit Kerala as the tagline ‘God’s own country’ became popular. That global recognition boosted our own sense of self-appreciation.

Then there was this phase of experiencing the newness of modernity when many people dismantled their old houses, threw away their antique furniture, got rid of the wooden arches and replaced them with modern-day architectural products. Those ethnic markers, however, found ready acceptance in the West as an Indian accent. The reverse psychology worked again to reinforce the value of ethnicity. A lot of jaali work and Burma teak have returned as have old trunks, chests and utilitarian metal items as a decorative comment on our legacy.

The years of Western minimalism have now ensured that our ethnicity is not over-the-top, but the fact is that it took at least 30 years for us to realise our worth in the world. Everybody is now realising that the top global brands they run after come to us when they have anything to do with handicrafts, use our embroidery, buy fabrics, appreciate our handlooms. We have something special about our ikats and tie-dye, though variants are available all around the world, and our weaving processes. So we have grown into that proud feeling of being an Indian. I remember wearing a Nehru jacket, bundi, or whatever it is you want to call it, for the past 30 years. This has survived only because it is very practical, suited to our climate, can sit as easily on a kurta as on an Armani shirt, is a slip-on, convenient accessory and still lets you wear India on your sleeves. Of course, the politicians always wore it but now every news reader, every corporate honcho, every businessman, almost everybody has one in the wardrobe. Not that the feeling wasn’t there, it’s just that we are now proud of wearing Indian.

The same sensibility has permeated fashion. There was a time when ethnic, couture, bridal and occasion wear were not considered “with it.” Yet today, this category generates massive business. If we as a people are appreciative of Indian fashion designers and giving them round-the-year business and they are able to grow from a mom-pop operation to boutique, factory and a larger scale, then it is perhaps the best time for the Indian fashion industry.

The domestic customer is now dictating terms of the market. And it is not just ethnic wear that is getting a boost, our consumer has coopted Western lines with equal glee, the evening gown now ubiquitous at galas and events. I remember gowns on the red carpet and at Navy and May Queen balls. Today, everybody wants a gown. Yes, the demand for ethnic and Indo-Western has peaked which has, in fact, cascaded and streaked into other lines, be it Western or corporate. Hotels, airlines, restaurants and brand offices are engaging our designers for interventions and styling. Some hotels and big corporations are exclusively helping out weaver clusters and buying uniform saris from them.

So I would say the tremendous absorptive potential of India is responsible for the spurt in the fashion industry. The demand of Indian customers and the fact that they have started to appreciate how much difference a fashion designer will make in their profile have been a catalyst. After Bollywood and sports, fashion is what grabs the most eyeballs and has emerged as a key component of soft diplomacy. It is this ascension which has compelled our designers, some of whom were touting their placements in foreign stores and partnerships as successes and some who managed to set up individual outlets overseas, get real.

How have fashion weeks helped in this transition?

Consistently. Our first fashion week was in 2000 and it has only been a mere 18 years. In the first five or six years, there were no takers at all, but it boomed in the last 10 years when every small city tried to have an edition of its own. There were many fly-by-night operators too, who used the platform for promotion rather than generating any serious business, but they fizzled out. The FDCI has consistently stood by the business of, by, and for the designer and ensured the showcase is intended to fuel big buys and orders. So really there is no compromise that way. Our sponsors have stayed with us over the years, which proves our brand worth and credibility. We have had 34 editions so far and I have been part of the last 10. Within these 10-plus years, 40-45 shows have taken place during each outing. Some shows have been a conglomerate of four or five designers. I have been a part of more than a 1,000 shows myself and to maintain consistency has been a huge effort by the FDCI and its team. The pressure of ensuring a quality outing has meant the designer has been on his/her feet, has evolved with the times and is continuously churning out newer designs, output and innovation.

Ours is not a slow industry. More so in the times of social media when you are exposed to everything happening then and there. The awareness is so high that you can’t afford to be complacent anymore. So Indian fashion has changed much faster in the past five years than maybe any other industry. Because it is really happening on a day-to-day basis.

But many people complain of a glut, of too many fashion weeks diluting their very purpose?

I agree there was a big fashion fatigue and I am not even saying that we are out of that as yet, but nobody gets tired of looking at a fashionable outfit every single minute on Instagram. So what you call fashion fatigue has transmuted into curiosity. You might be over-exposed but people are still consuming it hungrily. That is the reason why we are still in business. Also, there is a demographic mix of baby boomers to millennials. One generation is happy with slow fashion and the other wants fast fashion. The demand is taut between these two arcs. That’s also the reason why even online entities now want a touch-and-feel flagship store.

So how have online retail counters and social media changed the economics of fashion?

Tremendously; they have made fashion gettable. The FDCI is lucky to have an e-commerce player. That started on the basis of participation in a fashion week. But sooner or later, they had to develop their own platforms to be strong enough and they have done it very successfully. The day is not far when we might have online fashion shows and if the market goes that way, so will the fdci. Personally, I am a bit old world though and would not want to let go of the ramp up close.

What do you make of the design fluidity that has spilt over from what we wear to the smallest accessories and utilities?

For a long time, India was deprived of foreign products. Just to get hold of an Ikea magazine was considered a luxury. People were not exposed to possibilities. Now that they are, they know they can roll out a thousand products out of one kind of weave or motif. Imagine the multi-billion scale of diversification. We never had a design school, there was NIFT and that too is also not more than 20 years old. What was experimental product design can now be utilitarian and mass grade. Young people are choosing fashion as a career even more now because you have to immerse yourself in it as much as engineering, medicine, or applied science to get the results.

How did you find your way into fashion?

I did not want to get into my family business of automobile spare parts and even though I joined because of family pressure, my heart was always set on the export market of handicrafts, textile and apparel. Fresh out of college, I left for Europe, Canada, and America with a bagful of samples. That exposure and experience worked in understanding how brand India could be marketed. I was fortunate I had achieved what I wanted to in my corporate life before I came to the FDCI, so I had already worked with the best.

One of the largest sourcing companies in the world bought my intellectual rights. I achieved large turnovers of my own, so I was ready to give everything to the fashion industry without expecting anything in return. It is a blessing in disguise that I got so much out of the industry. It has made me value people. It has put me in the limelight without me wanting it. Even the 20-25 years of solid work I did in my earlier field got more recognition.

I have worked with all fashion designers and done many alliances with them. I have made so many different products using their inspiration and given them additional lines to work with. That to me is a very big satisfaction. Most importantly, we have always had a healthy financial position. The FDCI is now capable of doing many things.