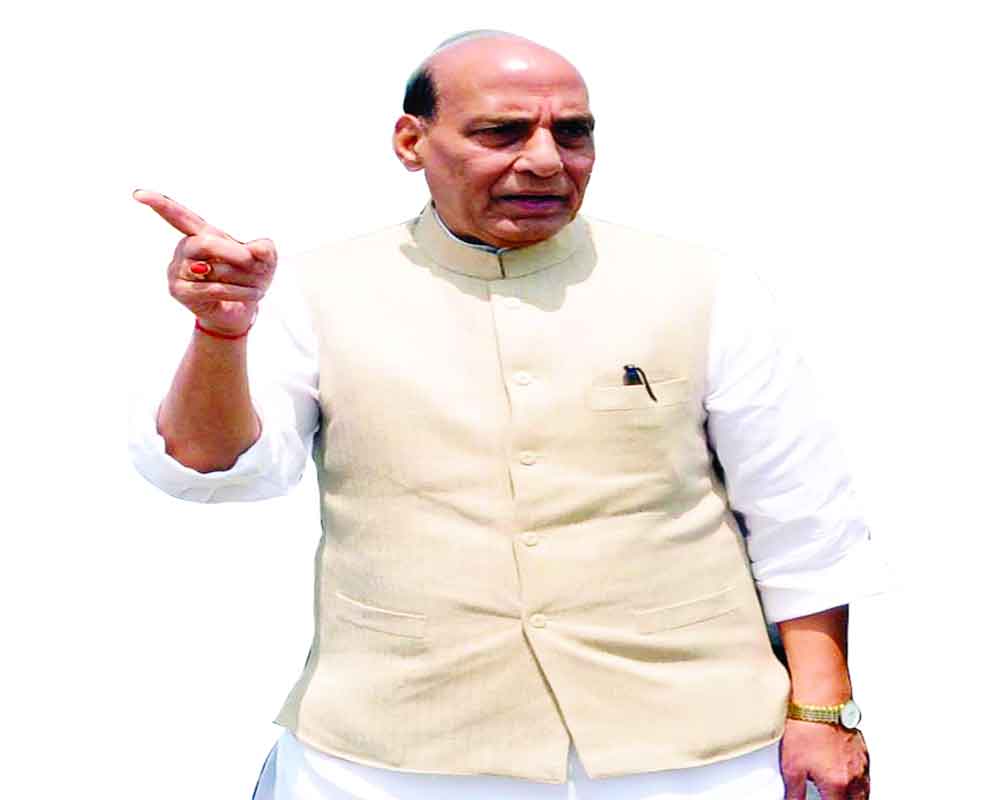

Rajnath Singh was to contest the elections from Mirzapur in 1977 immediately after the Emergency but at the last moment, a seat swap between Jana Sangh and the Janata Dal saw him give it up. Singh could have fought the elections independently, as advised by few people, as he was a very popular young leader. But, he not only chose to stick by the party’s decision, he also came out in the support of the candidate who replaced him in a way that was not imaginable, writes GAUTAM CHINTAMANI in his book, Rajneeti: A Biography of Rajnath Singh. An edited excerpt:

The day of 12 July 1975 started like any other day for Rajnath Singh and after his morning exercise and bath, as he was about to step out, he was arrested by the Mirzapur police under MISA. By the time of his arrest, Singh had become known as a formidable force who had galvanized the JP movement programmes, and the authorities were instructed to not take him lightly. No one arrested under MISA was allowed any access to people outside, and Singh being one of the prominent detainees in the area, all contact was ruled out.

After he had spent a few days in Mirzapur jail, Singh was transferred to the Naini Central Jail near Allahabad. Hearing about the transfer, Savitri and Gujarati Devi decided to meet Singh at Mirzapur railway station where the train carrying him was scheduled to make a brief stop. Savitri had not seen her husband since the day he was arrested, but it had been a few months since Gujarati Devi had seen her son. On the day Singh was being ferried by train, both reached the station hours before the train was due. Every moment that passed filled them with anxiety. No one knew how long he would be under detention and the news of thousands more being hauled up across the country added to their fears.

The train arrived slightly later than it was due and soon the platform was full of police personnel. In a matter of seconds, Gujarati Devi and Savitri were separated from the train by a sea of humanity dressed in khaki. Handcuffed and held by policemen at the elbows, Singh emerged from the train hoping to meet his wife and mother. He spotted them at some distance but the sheer number of policemen between him and his family made it impossible for him to meet them. At twenty four, Singh, who had been a physics lecturer at a local college a few years ago, was just a young man taking his first steps in politics but the security personnel treated him like a hardened criminal. Some of the people whom Singh had worked with during the JP movement had also made it to the railway station and they began sloganeering. It was impossible for Singh to hear his mother or Savitri in the middle of all the cacophony and sloganeering, asking him to carry on with his struggle. As the policemen whisked Singh away, he finally heard Gujarati Devi. Even in the face of uncertainty about what lay ahead for her son, the only thing Gujarati Devi told him was not to bow down. ‘Babua, maafi maange ki naheen! Chahe umar bhar kaalkothri mein kyon na katt jaye ... kabhi sar mat jhukana.’ (Never beg for forgiveness, my son, even if you have to spend your entire life within the confines of a prison ... never bow down). Hearing his mother urging him to never give in filled Singh with pride as he fought back the tears that had welled up. Many policemen too were moved by Gujarati’s comment. That was the last time Singh ever saw his mother.

During the first few weeks in Naini Central Jail, Rajnath Singh was put in solitary confinement. Despite the bleak scenario and the uncertainty, Singh never lost faith. This enforced isolation gave him the time to reflect on the ideals and the principles instilled in him by his father and the values for which his mother was willing to let go of the chance to see her youngest son ever again.

A while later, when the solitary confinement ended, Singh saw some of his friends move applications for release on parole but he refused to do so. For Rajnath Singh, the time in jail made him reassess the ideals for which he was willing to put his life on the line. There were times when he caught himself thinking about how things had come to such a pass in the political history of the country. Irrespective of the differences in ideology or political affiliation, most politicians and people in public life, he believed, had one goal: serve the people and the country. Despite the cynicism about politicians that was beginning to set in among the public, the idea of making India a strong nation, one that would attract the envy of the world, was perhaps still the singular thought amongst people operating in the political sphere. In this context, the total disregard for propriety and decorum, and the high-handedness that the government displayed towards those in the Opposition and anyone who questioned it, in the process pushing the country into an era of darkness where basic civil liberties were snatched away, did not make much sense for young people such as Singh. For them, politics, at least up until the Emergency was declared, was about a debate between two or more theories and ultimately it was the voter who decided on which set of ideas suited them.

The Emergency was a tool to elicit a political price from those who challenged Indira Gandhi, but, for many, it extracted much more. Gujarati Devi had kept abreast of the unfolding situation and counted the days to her son’s return. She often asked the same question every time she met any of her nephews: ‘Babua kabhin aayen?’ (When will my lad return?) One of Rajnath Singh’s cousins told Gujarati Devi that MISA would be retracted in a year’s time and so, if everything went off well, Singh would probably be released on 25 June 1976. Through the course of the first year of the Emergency, scores of mothers like Gujarati Devi kept track of the days and waited with bated breath for someone to repeal the law or the government to release those detained under it.

A year later, on the said date, 25 June 1976, Gujarati Devi asked the same nephew about Singh’s release, and unable to give her any good news, he told her that the government had extended MISA and no one had any idea how long it would take. It could well be another year. Gujarati Devi was unable to take it any more and suffered a stroke. She was rushed to the hospital and the doctors concurred she had had a brain haemorrhage. Her condition worsened over the next few days and, preparing for the worst, the doctor asked Savitri to inform her husband.

Upon hearing the news, Singh refused to move an application for a furlough to visit his mother in the hospital, preferring to absorb the blow silently. Every morning at sunrise, he hoped against hope that any news about his mother would be delayed by yet another day. The jail and the treatment meted out to him had not succeeded in breaking his spirit. The jail authorities were following orders from a dispensation powerful enough to brush away basic rights of one of the world’s most populous countries by a mere stroke of the pen. They had dented the self-esteem of many of the inmates and ensured that the person eventually walking out was not the same as the one who had gone in.

Singh remained determined to not letting anything undermine him mentally and more so when the news about his mother’s condition became public knowledge. He reminded himself of what his mother would have expected from him and carried on. It was in jail that Singh got to learn about his mother’s passing away and performed all the post-death rites including shaving his head within the confines of Naini Central Jail. To this day, Singh finds it difficult to stop tears welling up in his eyes every time he remembers his mother.

On 18 January 1977, Indira Gandhi called for fresh Lok Sabha elections that would be held in the month of March and although she also ordered the release of those her government had detained, the Emergency officially ended on 21 March 1977.

The Opposition soon galvanized people and left no stone unturned to make it amply clear that this was their last chance to pick between democracy and dictatorship. After his release, Singh found great support within his community that was aware of the hardships he had undergone during the Emergency. An entire generation of India’s political class that had been put through the strongest of fires was about to graduate and Singh was amongst them. Unlike the decision to not give tickets to some rising stars such as the ABVP students as the Jana Sangh felt they had been overly politicized during the Emergency, which could lead them to look at things in a different light, there was no predicament when it came to Singh. He became an automatic choice for the Lok Sabha ticket from Mirzapur. The principal Opposition parties-the Jana Sangh, the Bharatiya Lok Dal, the Socialist Party and the Congress (Organization)-had come together as the Janata alliance to fight the elections against Indira Gandhi. Singh began campaigning in full swing for the elections that were to be held between 16 and 19 Match 1977. But before voting day, an internal understanding between the Jana Sangh and the Lok Dal relegated him to the sidelines. An eleventh-hour seat-sharing arrangement between the parties that constituted the Janata alliance saw the Jana Sangh giving up Mirzapur in favour of Fakir Ali Ansari. As a result, the Jana Sangh could not pitch its candidate and the Lok Dal decided to field a locally recognized carpet manufacturer as the contender from Mirzapur.

The news of the change sent shockwaves across the city. Not just the Jana Sangh party workers but also the RSS and ABVP cadre offered their support to Singh. Much like the earlier elections, the RSS cadre was bound to play a significant role in mobilizing the electorate in favour of the Janata alliance as it had done for the Jana Sangh in the past. The word on the ground suggested that the joint cadre was willing to go against the executive if Rajnath Singh was not picked and some had even begun suggesting that he should fight the elections as an independent.

Singh made his way to the district collector’s office to withdraw his candidature, accompanied by a swarm of supporters. The sight was perhaps too intimidating for Ansari, the Lok Dal candidate, a soft-spoken Muslim gentleman who was known to Singh as well. As he entered the office, Singh offered him his best wishes. The district collector informed Singh that the time to withdraw candidature was over and his name would remain on the ballot paper. As Singh pondered over how to avoid a situation that would be detrimental for both the Jana Sangh and the Janata alliance, the clamour urging him to fight as an independent candidate grew louder amongst the cadre. Singh took a moment to think and decided to stand by the party. He told everyone that if the party was right in thinking of him as worthy enough to contest, how could it be wrong if it changed its mind due to some unavoidable circumstance? In a practical display of walking the talk, doing the right thing irrespective of the situation, which was also fast becoming a much talked about trait of Rajnath Singh, he offered all his support to the Janata alliance candidate. As he stepped out of the DC’s office, Singh addressed the crowd, underlining that it was his bad luck that the rules did not permit his name to be struck off the ballot paper. He told everyone present that if he got even one vote it would be tantamount to dishonouring his name. When the votes were cast and the ballots counted, Rajnath Singh did not get a single vote. To this date, he considers it to be a victory unlike any other in his entire life.

Excerpted with permission from Gautam Chintamani’s Rajneeti: A Biography of Rajnath Singh; Pengiun, Rs 599