It’s wrong to project the Gyanvapi mosque-Kashi Vishwanath temple row as an expression of hate; in fact, it’s an attempt at course correction

To dismiss the Gyanvapi mosque- Kashi Vishwanath temple controversy as a vile expression of hate, Hindu bigotry and a majoritarian excess is too reductionist to serve any constructive purpose. A more in-depth look at this issue — one that factors in Hindu sentiments and examines historical and archeological data — is necessary to come to an equitable solution. Hate is an expedient terminology to brand one’s ideological adversaries as radical and is consistently employed to silence those fighting for Hindu rights.

Challenging injustice is not hate. Hate is what was done to the Hindus. The physical destruction of a temple and its deity is a tangible expression of hate that surpasses any vocal vituperation; an act of unparalleled blasphemy far more offensive than any verbal indiscretion which no sane human can or should defend.

That this destruction involved the holiest of holy Hindu shrines adds insult to injury and magnifies the crime. The Kashi Vishwanath temple is the epicentre of Hinduism. Dedicated to Hindu God Shiva, this temple houses one of the 12 jyotirlings and dates back to at least the first century AD. Religious scriptures place its date of existence even earlier.

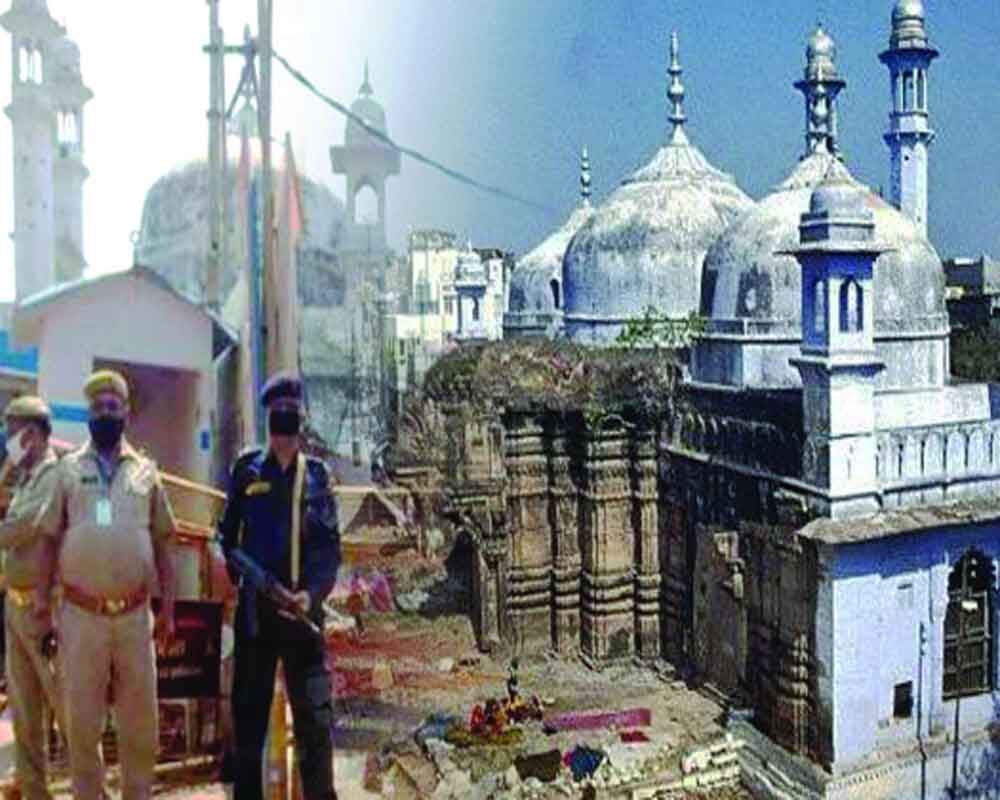

Over the years, this temple has been destroyed by Islamic invaders and rebuilt several times. The last known destruction was authorised by Moghul Emperor Aurangzeb in 1669, who erected a mosque in its place — the Gyanvapi mosque, named after the ancient wisdom well of the Hindu temple.

The current Kashi Vishwanath temple was built by Rani Ahilyabai Holkar, the queen of Indore in 1777 adjacent to the original site. The destruction of the Kashi Vishwanath temple was a spiritual apocalypse for Hindus; the ultimate desecration designed to crush their inner identity, dehumanise them and make them ripe for religious transformation.

That Aurangzeb demolished the Kashi Vishwanath temple and built a mosque in its place is not a historical conjecture open to debate or a fantasy of the Hindu right wing as some are prone to claim, but a fact firmed by irrefutable evidence. Aurangzeb stands indicted by his own written order and by the documentation of partisan Islamic chroniclers.

Maasir-i-Alamgiri, an authorised account of Aurangzeb’s rule, states: “It was reported that, according to the Emperor’s command, his officers had demolished the temple of Vishwanath at Kashi” (pp55. English translation by Jadunath Sarkar). A copy of the firman/order is still available at the Asiatic Library in Kolkata. Archaeological artefacts at the mosque site also confirm the demolition. Can we stifle this controversy by invoking the adage that history cannot be rewritten? True, history cannot be rewritten. But this is a digressive argument that fails to address the crux of the controversy. A more appropriate way to frame this dilemma is to ask this question: Can the wrongs of history be corrected?

The answer is in the affirmative and they should, wherever and whenever feasible. By allowing evil to go unchallenged, we not only condone wrong but become inadvertent protagonists of injustice. However, redress cannot be violent or vindictive; it should not target individuals or involve the loss of human lives. Material edifices like statutes of tyrants, usurped places of worship and names of cities and towns forcibly changed are fair game.

The ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement has now given us a precedence. If the statues of Christopher Columbus can be toppled in the US for his alleged infractions, and if the monuments commemorating King Leopold II — who exploited the people of Congo — can be dismantled in Belgium, why is it that an edifice that symbolises a far greater evil and one that impacts 1.4 billion Hindus is allowed to stand is the million-dollar question?

Agreed, the present-day Muslims cannot be held accountable for the misdeeds of medieval Muslim invaders. But when Muslims defend these historical atrocities and seek legal help to preserve the status quo, they not only identify themselves with the perpetrator but also with the vile deed itself; in effect knowingly and deliberately accepting responsibility for the crimes of Muslim invaders. It is this polarising activism and domineering mindset that has vitiated the socio-political climate which makes them culpable in current times.

Recourse to the Places of Worship Act, 1991, will not pass muster. That Act is discriminatory against Hindus in its syntax and violates the Constitution’s basic tenet by barring remedy of judicial review. It is a chimera to believe that secularism is tantamount to suppression of rights of the majority as implied by the Act. The sooner we scrap this Act, the better.

Muslims cannot remain in a state of opportunistic denial. They need to acknowledge past wrongs or alternatively disassociate themselves from those atrocities by willingly giving up places of worship that rightfully belong to Hindus. This will engender a sea of goodwill and further Hindu-Muslim amity. The ball is in the Muslim court.

(The author, a US-based academic and political commentator, frequently writes on current affairs in India. The views expressed are personal.)