The Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill, 2019, which prohibits commercial surrogacy but allows it for altruistic purposes, has once again put the spotlight on reproductive autonomy, women's rights and the extent to which the State should intervene

The newly-introduced Surrogacy (Regulation) Bill, 2019, passed by the Lok Sabha, has once again stirred the big debate regarding reproductive autonomy, women’s rights and the extent to which the State should intervene. The Bill prohibits commercial surrogacy but allows it for altruistic purposes. It mandates that the intending couple should have a “certificate of essentiality” and a “certificate of eligibility” that are issued upon fulfillment of certain conditions.

For instance, the couple must be Indian citizens and married for at least five years; the wife should be between 23 to 50 years of age and the husband between 26 to 55-years-old. They must not have any surviving child (biological, adopted or surrogate). However, this would not include a child who is mentally or physically challenged or suffers from life-threatening disorder or fatal illness. This apart, the couple must also fulfill other conditions that may be specified by regulations.

The Bill was introduced to clamp down on rampant commercial surrogacy, with India fast becoming a hub. Surrogacy is a $400 million a year business with an estimated 3,000 fertility clinics in major Indian cities, says a 2012 UN study.

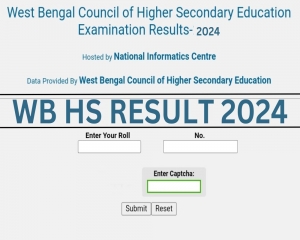

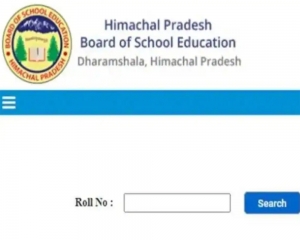

Worldwide, it is estimated that around 15 per cent of reproductive-aged couples are affected by infertility. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), the infertility rate in India is between 3.9 to 16.8 per cent. Infertility rates vary from State to State. While it is 3.7 per cent in Uttar Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh and Maharashtra, it’s 5 per cent in Andhra Pradesh and 15 per cent in Kashmir.

Hence, there’s a big population that needs help starting a family but the new law will make surrogacy inaccessible for this cohort. There are arguments for easy availability of the option for adoption in India, but in the end, the state shouldn’t decide how couples expand the family.

While this Bill makes altruistic surrogacy legal in India just like South Korea, Hong Kong and Vietnam, in most of the neighbouring countries it’s either banned or there are no regulations governing it. After widespread reports of Indian women travelling to Nepal once India enforced visa restrictions for foreigners commissioning surrogacy in India in 2013, the Supreme Court of Nepal ruled against commercial surrogacy in August 2015.

To date, however, normative standards on surrogacy have been relatively limited. The UN international human rights mechanisms have not yet taken up the issue of surrogacy in a focussed or uniform way. The UN Special rapporteur on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography has addressed the issue and highlighted the lack of regulation of commercial surrogacy. It has called upon countries to adopt legislation to protect the rights of women and children and develop and implement international standards.

Coming back to the Bill, another sticking point is that surrogacy remains only for the married heterosexual couples and completely excludes singles, live-in partners and same-sex couples.

The other problem that various sections of women groups and activists have with this Bill is that the following aspects are missing from it and must be addressed.

First, the reason for not having a common position on surrogacy as outlined in the Assisted Reproductive Technology (Regulation) Bill, 2017 is not having an integrated approach towards the use of assisted reproductive technologies.

Second, as per the definition of “infertility”, the Bill excludes women who conceive but are unable to carry a child through the period of the pregnancy due to miscarriage, fibroids, hypertension and diabetes. In some countries like The Netherlands, South Africa and Greece medical conditions that permit altruistic surrogacy are well-defined.

Third, the Bill includes a sub-clause for National Surrogacy Board to define “any other condition or disease” for which surrogacy may be allowed. For a robust implementation, the eligibility criteria should not be left to regulations but be part of the law.

Fourth, as part of the certificate of essentiality, the Bill outlines the following conditions, a certificate of proven infertility of one or both the partners from a District Medical Board; an order of parentage and custody of the surrogate child passed by a magistrate’s court. However, the Bill lacks any review or appeal procedure in case of rejection of the application.

Fifth, the surrogate mother is required to be a close relative of the intending couple. However, the “close relative” or the nature of this relationship is not defined.

While it provides flexibility to the intending couple to broaden the choice of surrogates, it may also be subjected to perceptional scrutiny at the time of receiving the certificate of essentiality.

Sixth, the eligibility criterion that specifies that the couple should be married for at least five years stops the couple from deciding the size of their family as per their requirement. It’s not clear that once infertility is established, why a couple should be made to wait for five years.

Seven, the criteria of not having “been a surrogate mother earlier” cannot be monitored until there’s a centralised system to record pregnancies in the country.

Eight, the purpose of imposing a focus on “altruistic surrogacy” is an assumption that it will not be exploitative or coercive. With commercial surrogacy, there is at least an option for stringent contract and legal provisions but it will be difficult to monitor altruistic surrogacy. There is enough evidence that families can also be exploitative towards women who may be coerced to become surrogates for close relatives. Thus, the argument that the altruistic surrogacy cannot be an exploitative arrangement does not stand.

From a surrogate mother’s perspective, there are several concerns like prevention of coercion or any other form of exploitation, legal counselling for the implications of surrogacy on health and lives, informed consent, access to remuneration for surrogacy, nature of the relationship with the legal family of the child, among others.

The Bill violates the fundamental rights of surrogates and potential parents. The banning of surrogacy will make it more discreet and underground, putting a lot of these women at further risk.

Despite all the intricacies of the Bill, it leaves us with these questions — Where is the choice of surrogate women? Will banning commercial surrogacy address all these pressing issues? Why ban surrogacy and not regulate it?

(The writer is Senior Technical Advisor, Advocacy and Accountability at International Planned Parenthood Federation, South Asia)