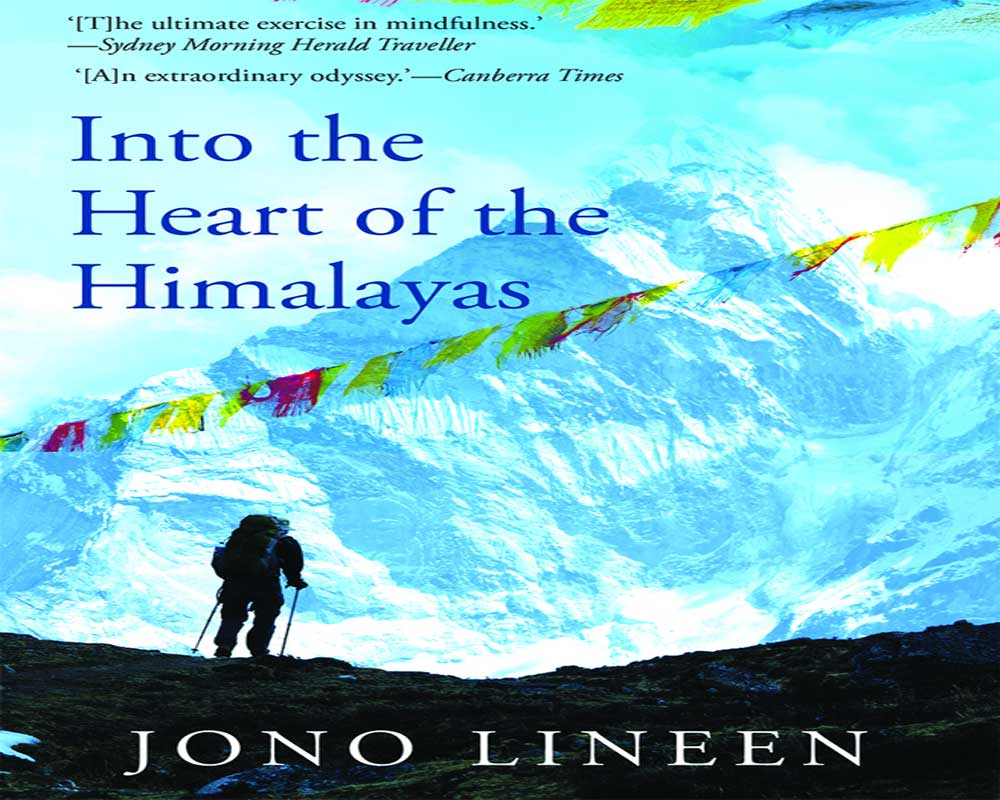

Name : Into the Heart of the Himalayas

Author : Jono Lineen

Publisher : Speaking Tiger, Rs 499

‘Walking induces clarity; its pace and simplicity engenders contemplation. In the conscious motion of my footsteps was heightened awareness’, recalls jono lineen in his book. Excerpt:

August 30

Kargil sits at the confluence of the Suru and the smaller Wakha rivers. It is a town of 10,000 people and is similar to many of its sister villages across the border in Pakistan with mud-brick, flat-roofed houses, concrete-block government buildings, a noisy bus park and a coating of dust on everything. But Kargil seemed a particularly dirty place. Maybe there was more traffic, and so more diesel exhaust stains on the walls and pools of oil by the side of the road, but there was also bright plastic garbage blowing in the wind and the laundry I saw flapping in the breeze was speckled with soot. Kargil is the last Muslim town before the shift to Buddhism and the town closest to the disputed border. It is a place on the frontier of religious and political divisions. Some residents resent the fact they are controlled by the Indian Army. As one man with a full beard, grimy jeans and the smell of old tobacco about him whispered to me in a tea shop by the bus park, ‘We are occupied by a force of idol worshippers and dark men.’

The place was not inviting, so after that quick cup of tea, during which I felt that half the men in the crowded chai shop were staring at me, I walked southeast down the Wakha Valley. I passed a few small villages along the way and after about twenty kilometres reached the confluence of the Wakha and Phokar rivers where I turned south and soon came to Phokar village, the first Buddhist community on my trek. Families were in the fields harvesting barley and because of the altitude, 3,200 metres, for the first time I saw yaks instead of goats grazing on the leftover stubble. I later learned the animals at Phokar were in fact a cross between yaks and cows called a dzo, bred for their higher milk production and more manageable demeanour.

The pungent smell of dung fires lingered in the air. The village looked prosperous. Every few hundred metres I passed two-storey mud-brick mansions with walls a metre and a half thick and flat roofs piled high with tight sheaves of freshly cut barley. The whitewashed walls were rubbed with diamond- shaped, blood-red markings, which I was to learn were protection from the evil spirits that many Buddhist Ladakhis believe lurk behind every ill-considered action. On the roofs of the houses, above the front doors, conical, one-metre-high terracotta incense burners billowed out peppery, juniper wood smoke; locals believe the particular smell attracts benevolent energies.

The majority of Ladakhis follow a Tibetan style of Buddhism which traces its local history back to the eighth century when the region was caught in the midst of the clash between Chinese and Tibetan expansionism. Control of the region moved back and forth between the two powers but in 842 Nyima-Gon, a Tibetan royal representative, took advantage of the chaos surrounding the separation of the Tibetan empire and annexed Ladakh for himself. This initiated a period of Tibetanization that has continued to this day. In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries Ladakh was invaded multiple times by Muslim armies. It was splintered but never completely conceded its independence and in 1470 King Lhachen Bhagan united the state and founded the Namgyal dynasty that still exists. In 1834 the Dogra army from Jammu successfully invaded Ladakh and made it part of Kashmir. During partition in 1947 Ladakh was invaded by the Pakistani Army. Kargil and Zanskar were occupied but eventually, after the Namgyal king signed the Instrument of Accession, which made the area an official part of the new Indian state, the Indian Army repulsed the invaders.

The trail up through the village was lined with stupas, earthen domes built upon square mud-brick pedestals and topped with brick or brass spires. Some were crumbling, while others seemed freshly painted. The stupas came in all sizes, some smaller than an upended shoebox, others more than seven metres high. Stupas were the earliest Buddhist religious monuments. Initially they were built to house what were thought to be relics of the Buddha. Over time they changed from being reliquaries to being objects of veneration themselves. Stupas came to be propitiated not for what they may have contained, but for what they represented. They have become architectural manifestations of the Buddha.

I tried to imagine the stupa as a devoted Buddhist might: the square base stepping upwards like a mind logically moving through levels of realization towards a state of enlightenment; the spherical core, both expansive and receptive, like the knowledge of the Buddha; and atop the dome a spire, a needle of fierce mind reaching for the highest state of consciousness.

By the roadside and scattered around the stupas were boulders, rocks and pebbles each chiselled with the ubiquitous Tibetan mantra, Om Mani Padme Hum: Om — the jewel inside the lotus flower — Hum. I found myself repeating it in time with my steps. Om — stride, Mani — stride, Padme — stride, Hum — stride. I had learned the mantra years before in Kathmandu and it had become a peaceful mumble that, to this day, sneaks up on me unconsciously.

I played with the words, quickened my pace and the mantra sped up. I slowed and the prayer lingered, working its way like a bass tone into my chest, sound and movement working together.

I bent down and picked up one of the mani stones. It was flattened and water-worn, a perfect river skimmer, smooth on one side, rippled with chisel work on the other. I slipped it into my trousers and felt it rubbing through the thin cotton of my pocket against my thigh.

I pitched my tent that night a few kilometres beyond Phokar in the lee of a wall constructed of thousands upon thousands of hand-carved mani stones, a work of devotion generations in the making. As I lay in my sleeping bag, a breeze blew through the stones, generating an undulating moan. The prayers serenaded me to sleep.

Into the Heart of the Himalayas, written by Jono Lineen is published by Speaking Tiger