For filmmaker Kanu Behl, films should respect the audience and create a space for them to question and even explore answers themselves. His short film, Binnu Ka Sapna, initiates a conversation on patriarchy. By Ayushi Sharma

The cyclical pattern of patriarchy is a globally recognised social condition. And evidently, a highly flawed phenomenon. One might even go a step forward and think of it as a social disorder. In almost every other home in the country, this cycle is justified and normalised. The real impact of being witness to the cycle, unfortunately, comes a full circle when children who grow up in such an environment, enter adulthood. Filmmaker Kanu Behl’s short film Binnu Ka Sapna talks about the journey of one such young man, initiating a larger conversation about the need to introspect.

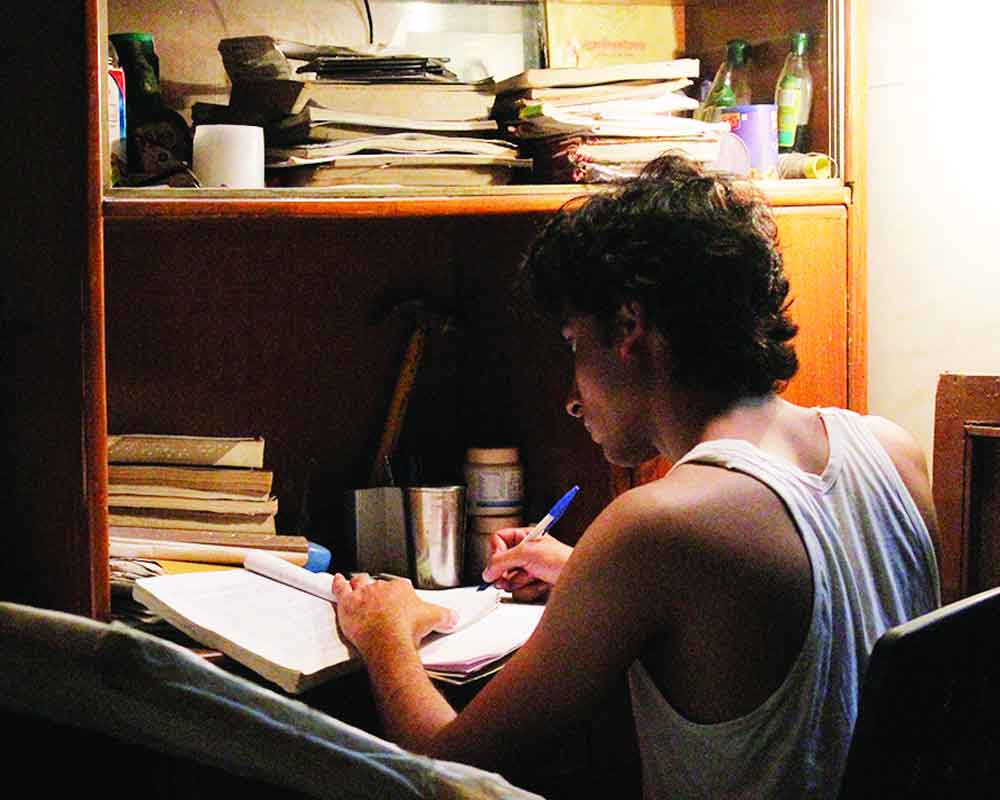

The story revolves around Binnu, who carries multiple lives that he has witnessed in his mind. His dreams get filtered and nightmares remain unshed. An uneasy cycle of violence bursts beneath the surface. Will it drench everyone around him? Binnu has grown up struggling with the echoes of the sound of his father slapping his mother, the first one being 25 years ago, when she merely emerged from the same room as her brother-in-law. Many years later, Binnu leaves home. At a party, he sleeps with his boss’ daughter, whom he falls in love with but things don’t go as planned. He leaves the town, engaging in another romance in another city. But something is not quite right. Slowly, a strange paranoia begins to engulf his being.

Behl says that Binnu Ka Sapna delves deep into a malignant mindset, trying to bare the ticking time bombs around us and illuminate the wicks that light them. The 32-minute narrative is his attempt to understand the anger within. He shares, “I went through a period where I raged and destroyed everything in my path. Irretrievably, irrevocably. Where did the roots of that anger lie? Did the anger root from a focal core or was it a constantly mutating unrecognisable beast? Its consequences and ripples, either way, rested on my individual doorstep. That’s how it began. In such times, you try to universalise your experiences to make them larger so that they don’t just stay restricted to your personal life.” He believes that Binnu Ka Sapna is a film that will be relevant even after decades because it tries to explore the impact of anger and violence on an individual as well as society. “It will help us reflect on the way we live our lives today,” adds he. The film, produced by Terribly Tiny Talkies and Colosceum Media, shows a harrowing transformation of a victim into an attacker, with society only serving as a catalyst.

The filmmaker believes that patriarchy is a disorder as it establishes the supremacy of one gender over the other. “It resonates with the capitalist structure, much like taking control over what belongs to the other. Even the institution of marriage in India has been subsumed with patriarchy, so much that one gender is only suppressing the other. In that sense, patriarchy is clearly dysfunctional. Having said that, such films are a fair rebellion and an initiative to structure such a thing that is defunct and clearly doesn’t work. So there is a need to have a nuanced debate about it,” says Behl, whose debut feature Titli has won eight international awards including the NETPAC and the Best First Foreign Film (2015) from the French Syndicate of Cinema Critics.

So what influences have shaped him to question the pattern of patriarchy because even Titli dealt with a similar issue. He says, “Thematically, I think they are two completely different pieces exploring different sides of the psychological spectrum. Titli was more about secularity and how patterns travel within a family.”

According to him, it is really important for a film to not be a sermon. He doesn’t think films are meant to be someone’s observation. “Generally it’s like... someone who knows everything about life and they are now trying to tell you,” says he. For him, a film should always respect its audience and have something to say and generate a conversation at the end of the day because now, he feels, the audience has matured and is accepting more complex narratives easily. Behl points out, “The grand 80s and the 90s failed our commercial cinema as they didn’t reflect the society. As a result, they didn’t mean anything to anyone at that time. Before that, the Bollywood of the 60s and the 70s was still doing very relevant work. From Guru Dutt, Raj Kapoor, Hrishikesh Mukherjee to Shyam Benegal, they made films that had as much to say as much as they entertained.”

Looking at the current trend in Bollywood, there has been a streak of biopics over the last five years, which has also become one of the favourite genres. However, Behl doesn’t have a very high opinion on this trend. He says, “It is incorrect to call them biopics. They are more of a hagiography. This streak is more of a substitute of Marvel-like superheroes in India because we don’t have any traditional superheroes here.”

And what about the theme of realism that is taking rounds in the Hindi film industry? The director feels that most of the social issue films are just public service advertisements. “I find a total lack of nuance and complexity in them. I don’t think that most of them are interested in exploring the issue beyond just preaching. For me, it is not what cinema is for. We all know what they are saying at the end of the day. They are just repeating the kahavatein. But where is the conversation around that issue?”

Well, Behl is someone who would make a film that has enough space for the audience to walk out with certain questions and have the rest of the conversation with themselves rather than someone passively telling them that this is the lie and that is the truth. “Films should leave enough space for the audience to come and interact. It must not close all doors by giving a particular solution. Someone shouting or giving a solution explicitly for people is almost propagandist. That is the power of cinema that people connect in an ideal scenario, which leaves them moved not just by the story or the plot but by what they notice that leaves them questioning the lives that they live. And that is where the change begins — with questions that are raised while you watch a piece of art and then every individual going back and finding answers for themselves,” says he.

(The film streams on MUBI India till January 22.)