While there is no guarantee that the RR hike will tame inflation, we can’t rule out the risks to growth

Normally, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) conducts a review once in every two months based on which the RBI makes policy announcements at the beginning of each of the following months viz. February, April, June, August, October, December.

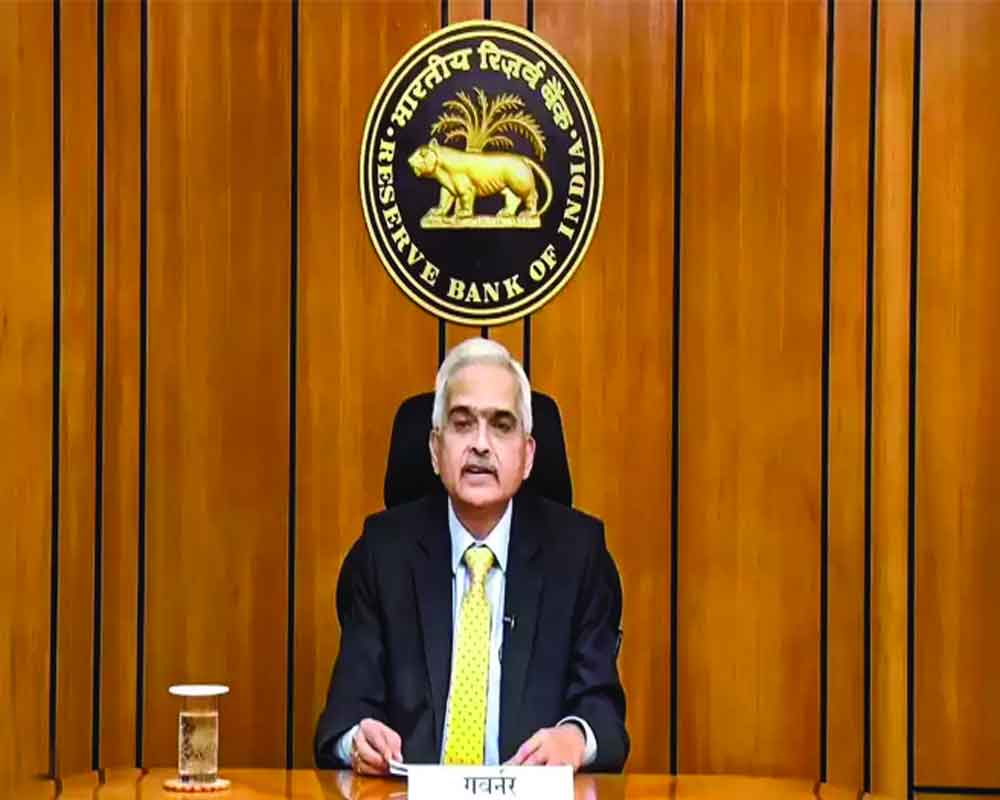

Deviating from this practice, in early May 2022, Governor Shaktikanta Das announced changes in the important monetary policy instruments.

Das increased the policy repo rate (interest rate at which the RBI lends to banks) or RR from 4 per cent to 4.4 per cent. He also increased the cash reserve ratio (percentage of a bank’s total deposits that it needs to maintain with the RBI as liquid cash; the bank does not earn interest on this liquid cash, neither can it use this for investing and lending purposes) or CRR from subsisting 4 per cent to 4.5 per cent. He kept the reverse repo rate (interest rate banks get on their surplus funds parked with the RBI) unchanged at 3.35 per cent.

The Governor has followed it up (this time based on MPC’s bi-monthly review), by announcing on June 8, further increase in RR to 4.9 per cent. However, he has kept the RRR and CRR unchanged at 3.35 per cent and 4.5 per cent, respectively. The RBI has also made a major shift from an ‘accommodative’ policy stance adopted for over three years—this was reiterated in early May 2022—to one what Das has described as ‘withdrawing accommodation.’

The RBI has justified a cumulative increase of 0.9 per cent in RR within a short span of over one month in terms of an overarching need to rein in inflationary pressure. For four months in a row, inflation—as measured by the consumer price index (CPI)—has been staying at over 6 per cent which is above the higher end of the medium-term target of 4 per cent (+/- 2 per cent) that the RBI has been mandated to ensure. Against this backdrop, one wonders as to why it waited for that long to get cracking on measures to contain inflation.

The big question is: how does a hike in the RR rate, increase in CRR, or ‘withdrawing accommodation’ help in taming inflation?

Theoretically, things should unfold in the following manner: A hike in RR implies that the banks will have to pay a higher interest rate on the money they borrow from the RBI. This will force them to charge more from their customers if only to recover the higher cost of their funds. Faced with higher borrowing cost, individuals, businesses/firms, etc., will borrow less from the banks leading to contraction in demand which in turn, will have a moderating effect on prices.

The increase in CRR is expected to yield a similar result by way of the RBI impounding more of cash from the banking system (for instance, the 0.5 per cent hike notified in May, 2022 is estimated to suck out about Rs 87,000 crore); hence less money available for onward lending. As for the impact of ‘withdrawing accommodation,’ let us first understand what ‘accommodative’ policy stance means.

Conceived in the context of the need to give a push to growth, an ‘accommodative’ stance unambiguously points towards a cut in RR in the future besides making more credit available. The RBI first talked about it in its bi-monthly monetary policy announced on June 6, 2019, when RR was reduced from the subsisting 6 percent to 5.75 per cent. Since then, this stance has

been maintained all along till the alteration made in the June 8

announcement.

Now, the withdrawal from accommodation connotes that henceforth, the RR will only increase (indeed, a hike of 0.25 per cent is likely in the next review in August 2022 when the rate will be restored to the pre-pandemic level of 5.15 percent before March 2020). Further, the RBI would like to see less cash with the banks so that indiscriminate proliferation of credit disbursements does not happen.

Things look fine but only as long as one remains within the bounds of the theoretical construct. They begin to bite the moment one comes out of it and looks at the reality.

Inflation, which was well within the target of 4 per cent (+/- 2 percent) until 2021-end, spurted in the beginning of 2022. It is clearly supply-driven, being the result of geopolitical tension, disruption in global supply chains, and steep increase in prices of commodities and, most importantly, food, fuel and fertilizers. In fact, hikes in food prices alone contribute around 75 per cent of inflation.

Fundamentally, the problem lies on the supply side but the thrust of RBI actions is on the demand side. That the banking regulator itself is not sure of its initiatives making a dent would be clear from its own projection of inflation during the first quarter of the current—7.5 per cent. In Q II, it is projected at 7.4 per cent, Q III 6.2 per cent, and Q IV 5.8 per cent. For the entire fiscal, the projection is

6.7 per cent.

While there is no guarantee that the RR hike will tame inflation, we can’t rule out the risks to growth as banks and non-banking finance companies (NBFCs) increase repo-linked lending rates and marginal cost of funds based lending rates (MCLR). This will lead to rise in EMIs of existing borrowers and make new home, vehicle and personal loans costlier in turn, impacting demand.

The effectiveness of monetary policy as an instrument of reining in inflation or promoting growth can’t be viewed in isolation from macroeconomic factors which can be a major bottleneck. For instance, during 2020-21, despite a steep cut in RR by 1.15 per cent and RBI pumping tons of money, GDP growth was -6.6 per cent. This was because the demand was annihilated, particularly during the first half (because of the Covid pandemic).

The other major impediments were decline in credit growth and high non- performing assets (NPAs) of banks. During 2021-22, apart from dilution in the impact of Covid, there was an increase in availability of credit aided by reduction in bank NPAs. As a result, GDP growth was 8.9 per cent even as inflation remained well within 6 per cent for most part of the year.

During 2022-23, even as RBI recognises the emerging risks to growth, the bigger problem is surging inflation. This calls for a frontal attack on the supply side. Already, the Modi Government has taken such measures as diversifying sources of supply (for instance, more oil from Russia), reduction in import duty on vegetable oils, and cut in central excise duty (CED) on petrol and diesel. More such

measures are needed.

As for the RR, a hike in it should be viewed from the perspective of protecting millions of depositors. Since 2020, they have already suffered due to a cut of at least 2 per cent in the interest earned on bank deposit.

Now, inflation is eroding their real income. The government should ensure that all banks increase the deposit rates in sync with the increase in the RR.

The banks also need to show some sensitivity to the borrowers, especially MSMEs and individuals, by not raising the lending rates or keeping the hike to a bare minimum. Given the improvement in their NPAs, low-cost funding from existing deposits and healthy balance sheet (during 2021-22, almost all public sector banks posted profit), they have the cushion to do it.

(The writer is a policy analyst. The views expressed are personal.)