India generates close to one-fifth of the world’s digital data yet hosts barely 2–3 per cent of global data-centre capacity. The result is stark: a country that creates the digital exhaust of 1.4 billion people depends heavily on infrastructure physically located elsewhere. Our firms, start-ups and even public systems increasingly rely on computing outside India’s borders.

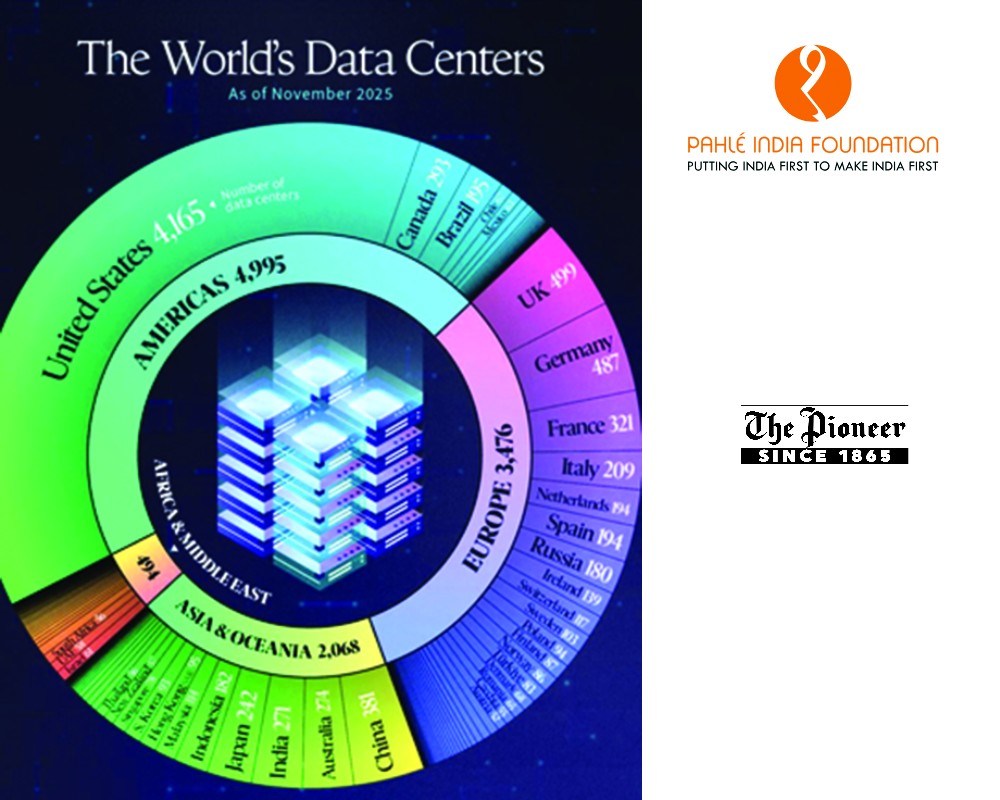

The global comparison is sobering (see Figure 1). Switzerland, with under ten million people, operates over a hundred data centres, while India, with 1.4 billion, has only around 150. That is roughly a hundred-fold gap on a per-capita basis. The paradox is that India, the world’s software factory, is still a compute importer.

Our domestic capacity today is about 1.2 gigawatts (GW) and is projected to rise to 2 GW by 2026 and 9 GW by 2032. These are healthy growth numbers, yet they remain modest relative to our digital footprint, and as AI workloads surge, the deficit will deepen unless compute is treated as national infrastructure.

The Job Question and the Real Economic Multiplier

It is easy to dismiss data centres as “job-poor”. Indeed, a typical 100 MW facility might sustain only around 50 long-term operational jobs and approximately 500 construction roles during its build phase. But this narrow view ignores the broader ecosystem they anchor: power infrastructure, fibre connectivity, cooling systems, server manufacturing and high-skilled services. The surrounding economic activity is expected to exceed `50,000 crore by FY 2027. For instance, in Andhra Pradesh, a `4,500-crore facility (by Adani Group and Google) is projected to create over 16,000 direct and indirect jobs, and a broader renewables-plus-data-centre cluster could add over 70,000 indirect jobs.

If India reaches 9 GW by 2032, even conservative multipliers imply tens of thousands of direct construction jobs, several thousand high-skill permanent roles and many times that number in the wider ecosystem spanning equipment, power, cooling, connectivity and services. That is not labour-intensive in the way textiles are, but it is deeply consequential for state economies looking to anchor clusters of high-wage activity.

How India Built the Wrong Architecture

India entered the data-centre era early but built the wrong model. Beginning in 2006, government funding created State Data Centres (SDCs) with a `1,623-crore outlay to host e-governance workloads. They replaced scattered server rooms but were designed for kilowatt-scale loads — not the tens of megawatts modern workloads need. Managed as government IT assets rather than industrial platforms, they remain

closed to private demand. India essentially built small server rooms and mistook them for a compute strategy.

The Policy Flip-Flop That Followed

Regulatory shifts deepened investor uncertainty. The 2018 Srikrishna Committee recommended storing a copy of all personal data in India and designating some as “critical”, to be stored exclusively onshore. This signalled a strong localisation push and could have guaranteed domestic demand. But the 2023 law took the opposite approach: most cross-border transfers are allowed unless countries are blacklisted. Investors, expecting guaranteed local demand, faced years of ambiguity followed by a diluted regime. The result was predictable: hesitation and slow capacity growth.

A Compute Hub Emerges on the East Coast

Against this backdrop, Visakhapatnam (Vizag) demonstrates what a coherent ecosystem can achieve. A planned US$15-billion investment, including a subsea cable landing and gigawatt-scale compute capacity, aims to position Vizag as a regional gateway. Andhra Pradesh targets 6 GW in five years, with 1.6 GW already committed. The vision includes Google’s largest India data centre and major renewable-energy integration. Andhra Pradesh’s IT Minister has separately articulated a vision of Visakhapatnam as “India’s Data City”.

While many states—Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Uttar Pradesh and Telangana—have data-centre policies offering tariff waivers and land subsidies, the absence of a national framework risks a race to the bottom. States compete on incentives but lack coordination on grid integration, cooling standards, renewable-energy tie-ups and geographic distribution.

A Coherent National Strategy

India’s compute transition will not happen by accident. It requires three deliberate shifts. First, treat data centres as core national infrastructure: link incentives to efficiency, water use and renewable PPAs. Second, adopt a national spatial strategy: coast to inland, cable-landing hubs to high-voltage corridors. Third, shift the state from operator to enabler: provide land, trunk infrastructure and clearances; let private capital build and run to global standards.

The Energy Constraint: Why Green Is Not Optional

Finally, no credible data-centre strategy can ignore energy. One expects data centres to consume nearly 30 per cent of national electricity in a decade. India’s share today is modest, around 0.8 per cent of total electricity demand, rising to 2.6 per cent by 2030. But the grid is weaker and reliability uneven. One megawatt of IT load requires roughly 1.2-1.5 megawatts of grid power, depending on efficiency.

Without pairing new capacity with dedicated renewable generation, the sector risks public backlash in a country where many households still face outages. The only durable solution is to structurally couple new data-centre capacity with new renewable-energy projects. For instance, Madhya Pradesh’s agreement with Submer Technologies is to develop up to 1 GW of energy-efficient, immersion-cooled, AI-ready data centres with up to 45 per cent energy savings and 90% water conservation relative to conventional designs. Another good example of the model India needs is Greenko’s 1,680 MW pumped-storage hydropower project at Pinnapuram in Andhra Pradesh, one of the largest of its kind globally. By pairing long-duration storage with solar and wind, it functions as a round-the-clock clean-energy backbone.

The Stakes

The next decade will be defined not by who writes the algorithms, but by who owns the infrastructure that runs them. If India remains a talent exporter but a compute importer, it will capture only a fragment of the value the AI era creates. We already generate the data. We already have the developers. What we lack is the infrastructure, the strategy and the execution strength to convert that into sovereign compute power.

Krishna V Giri. Distinguished Fellow & Special Advisor to the Chairperson and Payal Seth, Fellow. Both are at Pahle India Foundation; views are personal